[Original article on NHS Choices website]

Cataracts occur when changes in the lens of the eye cause it to become less transparent (clear). This results in cloudy or misty vision.

The lens is the crystalline structure that sits just behind your pupil (the black circle in the centre of your eye).

When light enters your eye, it passes through the cornea (the transparent layer of tissue at the front of the eye) and the lens, which focuses it on the light-sensitive layer of cells at the back of your eye (the retina).

Cataracts sometimes start to develop in a person’s lens as they get older, stopping some of the light from reaching the back of the eye.

Over time, cataracts become worse and start to affect vision. Eventually, surgery will be needed to remove and replace the affected lens.

Symptoms of cataracts

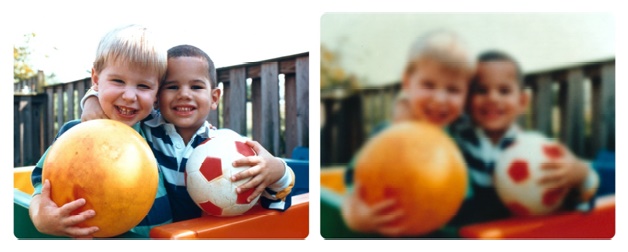

As cataracts develop over many years, problems may be unnoticeable at first. Cataracts often develop in both eyes, although each eye may be affected differently.

You’ll usually have blurred, cloudy or misty vision, or you may have small spots or patches where your vision is less clear.

Cataracts may also affect your sight in the following ways:

- you may find it more difficult to see in dim or very bright light

- the glare from bright lights may be dazzling or uncomfortable to look at

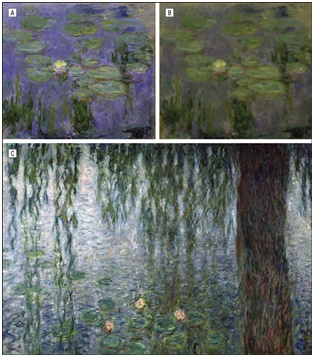

- colours may look faded or less clear

- everything may have a yellow or brown tinge

- you may have double vision

- you may see a halo (a circle of light) around bright lights, such as car headlights or street lights

- if you wear glasses, you may find that they become less effective over time

Cataracts aren’t painful and don’t irritate your eyes or make them red.

When to see an optician

If you have problems with your vision, make an appointment to see your optician (also known as an optometrist). They can examine your eyes and test your sight.

The optician may look at your eyes with a slit lamp or ophthalmoscope. These instruments magnify your eye and have a bright light at one end that allows the optician to look inside and check for cataracts.

If your optician thinks you have cataracts, they may refer you to an ophthalmologist or an ophthalmic surgeon, who can confirm the diagnosis and plan your treatment. These doctors specialise in eye conditions, such as cataracts, and their treatment.

Who’s affected

Cataracts are very common and they’re the main cause of impaired vision worldwide.

In the UK, most people who are aged 65 or older have some degree of visual impairment caused by cataracts. Men and women are equally affected.

Even though cataracts tend to affect older people (known as age-related cataracts), they can also sometimes affect babies and young children (known as childhood cataracts).

What causes age-related cataracts?

The reasons why age-related cataracts develop aren’t fully understood. Like grey hair, cataracts are an inevitable part of ageing that affect different people at different ages.

Cataracts are the result of changes in the structure of the lens over time. It’s thought that the cloudy areas in the lens may be caused by changes in the proteins that make up the lens. However, it’s not clear how or why getting older cause these changes to occur.

As well as your age, there are a number of other factors that may increase your risk of developing cataracts. These include:

- having a family history of cataracts

- having diabetes

- having other eye conditions, such as long-term uveitis

- eye surgery or an eye injury

- taking a high dose of corticosteroid medication, or taking corticosteroids for a prolonged period of time

Other factors that may possibly be linked to the development of cataracts include:

- smoking

- regularly drinking excessive amounts of alcohol

- a poor diet lacking in vitamins

- lifelong exposure to sunlight

As the exact cause of age-related cataracts isn’t clear, there’s no known way to prevent them.

Treating age-related cataracts

If your cataracts aren’t too bad, stronger glasses and brighter reading lights may help. However, as cataracts get worse over time, it’s likely that you’ll eventually need treatment.

Surgery is the only type of treatment that’s proven to be effective for cataracts. It’s usually recommended if loss of vision has a significant effect on your daily activities, such as driving or reading.

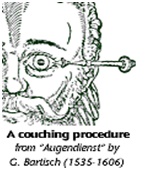

Cataract surgery involves removing the cloudy lens through a small incision in your eye and replacing it with a clear, plastic one. In most cases, the procedure is carried out under local anaesthetic (where you’re conscious, but the eye is numbed) and you can usually go home the same day.

Almost everyone who has cataract surgery experiences an improvement in their vision, although it can sometimes take a few days or weeks for your vision to settle. You should be able to return to most of your normal activities within about two weeks.

After the operation, your plastic lens will be set up for a certain level of vision, so you may need to wear glasses to see objects that are either far away or close by. If you wore glasses previously, your prescription will probably change. However, your optician will need to wait until your vision has settled before they can give you a new prescription.

Read more about recovering from cataract surgery.