Scientists aim to revolutionise British diets by slipping more UK-grown beans into our daily bread.

Researchers and chefs at the University of Reading aim to encourage British consumers and food producers to switch to bread containing faba beans (commonly known as broad beans), making it healthier and less damaging to the environment.

The £2 million, three-year, publicly-funded ‘Raising the Pulse’ project has officially begun and is announced today (18 January 2023) in the Nutrition Bulletin journal.

Five teams of researchers within the University of Reading, along with members of the public, farmers, industry, and policymakers, are now working together to bring about one of the most significant changes to UK food in generations.

This is by increasing pulses in the UK diet, particularly faba ( fava beans)beans, due to their favourable growing conditions in the UK and the sustainable nutritional enhancement they provide.

Despite being an excellent alternative to the ubiquitous imported soya bean, used currently in bread as an improver, the great majority of faba beans grown in the UK currently go to animal feed.

Researchers are optimising the sustainability and nutritional quality of beans grown here, to encourage farmers to switch some wheat-producing land to faba bean for human consumption.

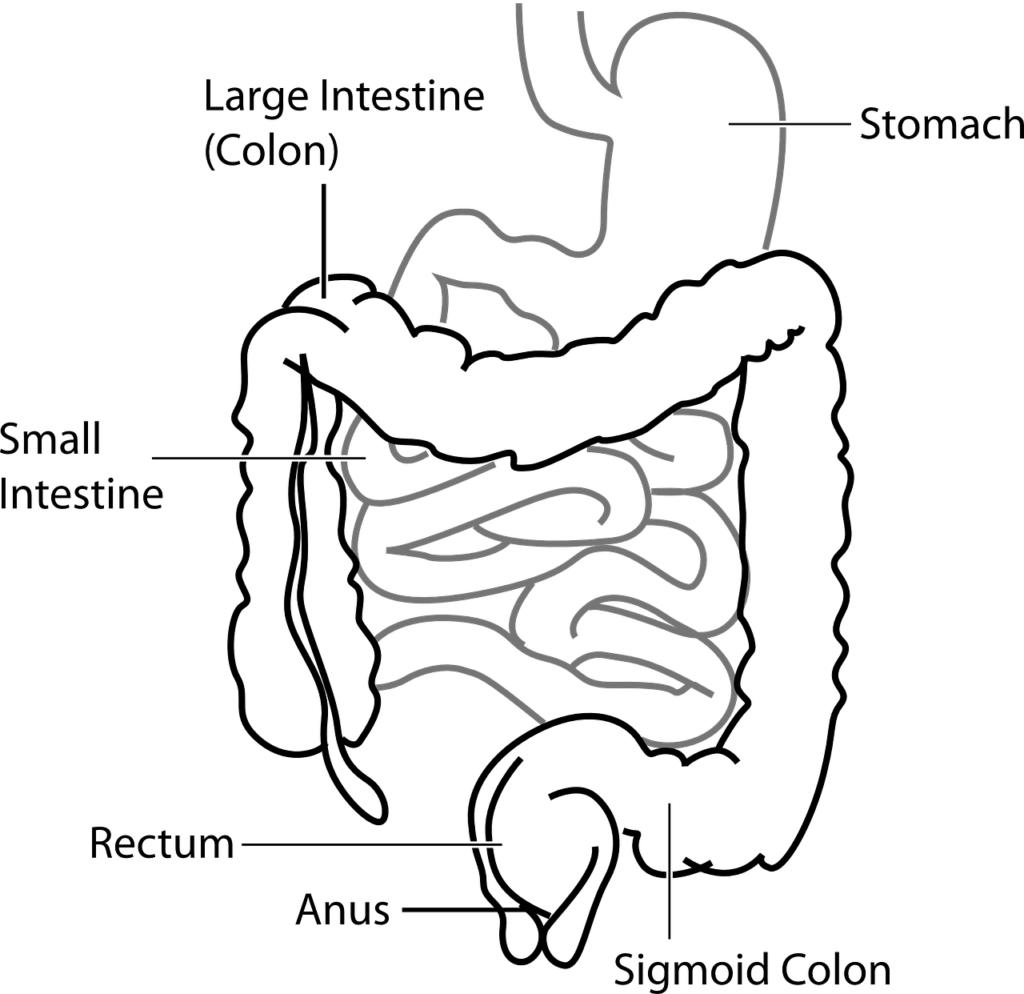

Faba beans are exceptionally high in easily digested protein, fibre, and iron, nutrients that can be low in UK diets. But most people are not used to cooking and eating faba beans, which poses a significant challenge.

Professor Julie Lovegrove is leading the ‘Raising the Pulse’ research programme. She said: “We had to think laterally: What do most people eat and how can we improve their nutrition without them having to change their diets? The obvious answer is bread!

“96% of people in the UK eat bread, and 90% of that is white bread, which in most cases contains soya. We’ve already performed some experiments and found that faba bean flour can directly replace imported soya flour and some of wheat flour, which is low in nutrients. We can not only grow the faba beans here but also produce and test the faba bean-rich bread, with improved nutritional quality.”

‘Raising the Pulse’ is a multidisciplinary research programme funded by the UKRI Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council as part of their ‘Transforming UK Food Systems’ initiative.

As well as consulting and working with members of disadvantaged communities, studies will use our novel foods at the University of Reading’s student’s halls of residence and catering outlets.

This links ‘Raising the Pulse’ with Matt Tebbit, who runs the University’s catering service and leads the University’s ‘Menus for Change’ research programme. He said: “Students will be asked to rate products made or enriched with faba bean, such as bread, flat bread, and hummus. They will be asked questions about how full they felt, for how long and their liking of the foods. It is hoped that faba bean will improve satiety, as well as providing enhanced nutritional benefits in products that are enjoyable to eat.”

Before products are tested, the beans must be grown, harvested and milled. ‘Raising the Pulse’ seeks to improve these stages as well. Researchers will be choosing or breeding healthy and high-yielding varieties, working with the soil to improve yield via nitrogen fixing bacteria, mitigating environmental impacts of farming faba beans, planning for the changing climate, and more.