Strategy could restore tissue balance and target cells that contribute to aging-related diseases

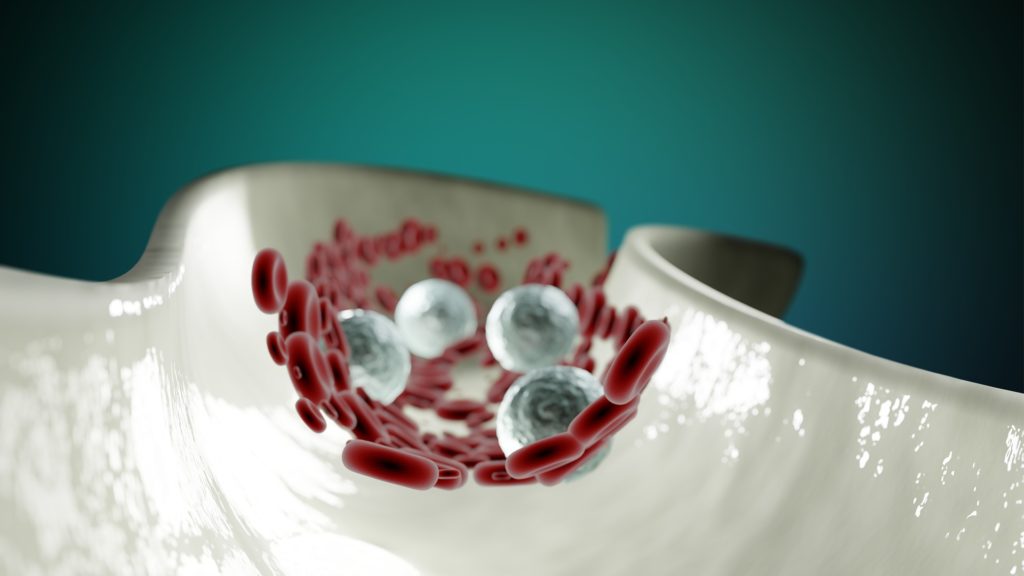

Ageing, or senescent cells, which stop dividing but don’t die, can accumulate in the body over the years and fuel chronic inflammation that contributes to conditions such as cancer and degenerative disorders.

In mice, eliminating senescent cells from aging tissues can restore tissue balance and increase healthy lifespan. Now a team led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of Mass General Brigham (MGB), has found that the immune response to a virus that is ubiquitously present in human tissues can detect and eliminate senescent cells in the skin.

For the study, which is published in Cell, the scientists analyzed young and old human skin samples to learn more about the clearance of senescent cells in human tissue.

The researchers found more senescent cells in the old skin compared with young skin samples. However, in the samples from old individuals, the number of senescent cells did not increase as individuals got progressively older, suggesting that some type of mechanism kicks in to keep them in check.

Experiments suggested that once a person becomes elderly, certain immune cells called killer CD4+ T cells are responsible for keeping senescent cells from increasing. Indeed, higher numbers of killer CD4+ T cells in tissue samples were associated with reduced numbers of senescent cells in old skin.

When they assessed how killer CD4+ T cells keep senescent cells in check, the researchers found that aging skin cells express a protein, or antigen, produced by human cytomegalovirus, a pervasive herpesvirus that establishes lifelong latent infection in most humans without any symptoms. By expressing this protein, senescent cells become targets for attack by killer CD4+ T cells.

“Our study has revealed that immune responses to human cytomegalovirus contribute to maintaining the balance of aging organs,” says senior author Shawn Demehri, MD, PhD, director of the High Risk Skin Cancer Clinic at MGH and an associate professor of Dermatology at Harvard Medical School. “Most of us are infected with human cytomegalovirus, and our immune system has evolved to eliminate cells, including senescent cells, that upregulate the expression of cytomegalovirus antigens.”

These findings, which highlight a beneficial function of viruses living in our body, could have a variety of clinical applications. “Our research enables a new therapeutic approach to eliminate aging cells by boosting the anti-viral immune response,” says Demehri. “We are interested in utilizing the immune response to cytomegalovirus as a therapy to eliminate senescent cells in diseases like cancer, fibrosis and degenerative diseases.”

Demehri notes that the work may also lead to advances in cosmetic dermatology, for example in the development of new treatments to make skin look younger.