Polling finds while majority appreciate importance of recording and sharing their wishes, less than 1 in 10 have done so

Compassion in Dying is today (Wednesday 30 May 2018) launching a new publication designed to help people think about their priorities for the future and make plans for their treatment and care. Officially endorsed by the Royal College of Nursing, Planning ahead: My treatment and care aims to support people to discuss and record their wishes so they can get on with living life, knowing they have prepared for the future.

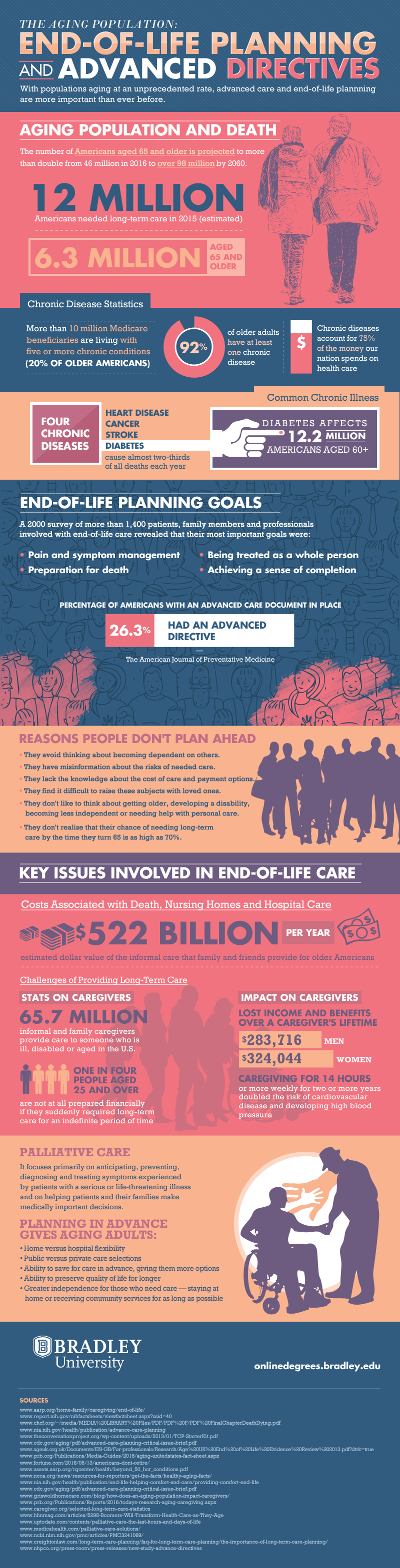

Polling conducted by YouGov in 2018[1], commissioned by Compassion in Dying, found that the vast majority (87%) of the public feel it is important that healthcare professionals caring for them know their wishes for future treatment. Top of their end-of-life concerns were ‘to have my symptoms and pain well controlled’ (23% listed this as their top priority) and ‘to be able to maintain by dignity and independence’ (20% listed this as their top priority). Just one in ten (10%) said they would want a doctor to make final decisions regarding their treatment and care if they were to become unable to make these choices for themselves.

Despite this, less than one in ten people have recorded their wishes in a legally binding way, either by making an Advance Decision (‘Living Will’) which allows someone to state whether they want to refuse life-prolonging treatment in certain circumstances (4%), or by making a Lasting Power of Attorney for Health and Welfare to appoint a trusted person(s) to make healthcare decisions on their behalf (7%). This means that doctors may be left to make important decisions without knowing a person’s values and preferences.

Peter Coe, 69, from Lyme Regis, whose experience is featured in Planning Ahead, is well aware of the benefits of discussing and recording healthcare wishes with loved ones. He explained:

“My dad had memory problems and wanted me to support him in enforcing his healthcare decisions and ensuring that his choices were undertaken. He made me his attorney for health and welfare, which provided an opportunity to discuss his wishes for the future.

“Sadly, in 2016 we were told his kidneys had failed and Dad didn’t have the capacity to make a decision over whether to opt for dialysis. We were told it might delay the effects for a few months but would involve arduous trips to the hospital several times a week. At the time Dad was living alone with support for daily tasks from his carers and me, and being able to spend his days in the garden, watching the sea, was very important to him. He had previously discussed what decision he would have made in such circumstances. I therefore felt confident that I could make the decision to refuse dialysis on his behalf, while ensuring he was comfortable and pain-free.

“It was a hard decision to make and I had to discuss it thoroughly with the

doctors, but it would have been much more difficult if I hadn’t spoken to Dad about his priorities. I knew it was what he would have wanted and as a result he was able to spend his final months doing the things he loved most, seeing his family and enjoying his garden.”

Planning Ahead explains in simple language the information people need to understand how treatment and care decisions are made, how they can plan ahead to ensure they stay in control of these decisions, and who to talk to and share their wishes with. It also includes answers to the common concerns that Compassion in Dying hears on its free information line such as, ‘can I have a ‘Living Will’ as well as a Lasting Power of Attorney for Health and Welfare?’, ‘can anyone override my wishes?’, ‘how will it feel to plan ahead?, and ‘is it expensive?’

Natalie Koussa, Director of Partnerships and Services at Compassion in Dying, said:

“We produced Planning Ahead because sadly any of us could become unwell and unable to tell the people around us what we do or do not want. By making plans now, you can record your preferences for treatment and care so that if you are ever in that situation, your wishes are known and can be followed. It gives you control and allows you to express what is important to you, providing peace of mind. Planning ahead means you can get on with living, safe in the knowledge that if an illness or injury leaves you unable to make decisions about your treatment and care, it will be easier for those around you to respect and follow your wishes.

“We are thrilled to have official endorsement from the Royal College of Nursing and the backing of other leading organisations in the sector, such as the Alzheimer’s Society. We hope Planning Ahead will be a valuable tool for individuals, their loved ones and health professionals alike.”

Amanda Cheesley, Professional Lead for Long Term Conditions and End of Life Care at the Royal College of Nursing, said:

“We are delighted to endorse Planning Ahead. Discussing death with family and friends and letting them know our wishes can help ensure people’s experience of care at the end of their life is as personal and compassionate as possible.

“The more we make talking about future treatment and end-of-life care a normal and sensible thing to do, the less frightening it will be for patients. This useful and easy to read booklet will be helpful to many people.”

Jeremy Hughes, Chief Executive Officer at Alzheimer’s Society, added:

“This is a valuable resource to help anyone think about what kind of care and treatment they would want in the future. It can be an incredibly emotional and difficult time when making these decisions and this guidance will help walk people through all the aspects that need to be considered. This is particularly important for people living with dementia, as they may not be able to make these important decisions later on.

“This guide can also be a useful tool to start conversations with those closest to a person with dementia and it can be reassuring for wider families and friends to have some clarity about what someone wants for the future. Too many people with dementia die with their wishes unknown and unmet. This publication seeks to empower people with dementia and ensure their rights are upheld.”