Neuromyelitis optica (NMO), also known as Devic’s disease, is a rare neurological condition.

Neurological conditions are caused by disease or damage to the brain, spinal cord or nerves.

NMO most commonly affects the optic nerves and spinal cord, which can lead to optic neuritis and transverse myelitis (see below).

Some people may only experience optic neuritis or myelitis but may have the aquaporin-4 antibody (also see below). In such cases, a person is said to have an NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD).

Each person with NMO will experience different symptoms and require individually tailored care and support.

Some of the main symptoms of NMO include:

muscle weakness – reduced strength in one or more muscles that can affect mobility

impaired eyesight

nerve pain – which can be a sharp, burning, shooting or numbing pain

spasms and increased muscle tone – from nerve damage that affects muscle control

bladder, bowel and sexual problems

NMO UK has more information about the symptoms of NMO.

Optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is inflammation of the nerve that leads from the eye to the brain. It causes a reduction or loss of vision, and can affect both eyes at the same time.

Other symptoms of optic neuritis include eye pain, which is usually made worse by movement, and reduced colour vision where colours may appear ‘washed out’ or less vivid than usual.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is inflammation of the spinal cord. It causes weakness in the arms and legs which can range from a mild ‘heavy’ feeling in one limb, to complete paralysis in all four limbs.

It may cause numbness, tingling or burning below the affected area of the spinal cord and increased sensitivity to touch, cold and heat. There may also be tight and painful muscle contractions (known as tonic muscle spasms).

Relapses in NMO

An attack or relapse of NMO results in the nervous system becoming inflamed. The inflammation usually occurs in the optic nerve and spinal cord, and causes new symptoms or the recurrence of previous symptoms.

Less common symptoms of NMO can include unexplained nausea and vomiting, unexplained itching and tonic spasms (painful muscle contractions). In someone with known NMO, these symptoms may signify a new relapse.

NMO symptoms can range from mild to severe. In some cases, there may only be one attack of optic neuritis or transverse myelitis, with good recovery and no further relapses for a long time.

However, in severe cases, there can be a number of attacks which lead to disability. Disability occurs because the body can’t always fully recover from damage caused by the attacks on the spinal cord and optic nerve.

NMO UK has more information about NMO relapses.

What causes NMO?

NMO is an autoimmune condition, which means a person’s immune system (the body’s natural defence against illness and infection) reacts abnormally and attacks the body’s tissues and organs.

An antibody against a protein called aquaporin-4 is present in the blood of up to 80% of people with NMO.

Antibodies are proteins produced by the body to destroy disease-carrying organisms and toxins.

In NMO, the immune system attacks aquaporin-4 which damages the myelin sheath (the protective layer that surrounds nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord and helps transmit nerve signals).

Who’s affected by NMO?

NMO is a rare condition. In Europe, it’s estimated that there’s one case of NMO for every 100,000 people. In the UK, it’s thought that NMO affects less than 1,000 people.

NMO can affect anyone but it’s more common in women than men, with about four females being affected for every male.

Although the condition is thought to be more common in people of Asian and African descent, an increasing number of white (Caucasian) people are also being diagnosed.

Diagnosing NMO

It’s important that NMO is correctly diagnosed. It can sometimes be confused with multiple sclerosis, which also affects the brain and spinal cord and has similar symptoms. However, the treatment is different.

A neurology specialist will discuss your symptoms and medical history with you.

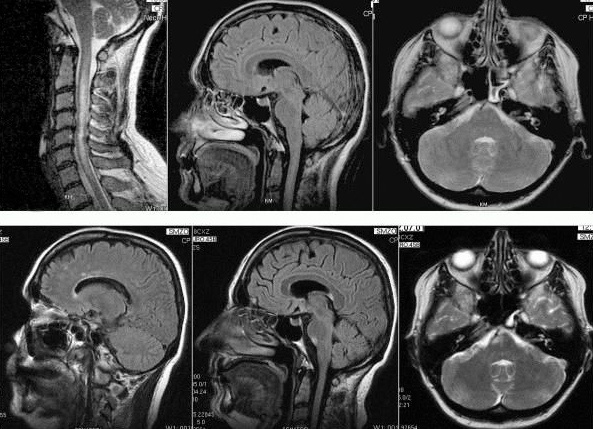

You’ll have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of your brain and spinal cord. Some people with NMO (up to 60%) have lesions on their brain and spine, which are different to the lesions of someone with MS.

A blood sample will be taken and tested for aquaporin-4 antibodies.

A lumbar puncture is another test you may have. A sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is taken from the spine using a hollow needle that’s inserted into the lower part of the spine.

The fluid sample will be sent to a laboratory to be tested and to look for evidence of conditions affecting the brain, spinal cord or other parts of the nervous system.

In some cases of transverse myelitis, there’s an increase in the level of proteins or white cells.

NMO UK has more information about how NMO is diagnosed.

Treating NMO

There’s no cure for NMO, so treatment aims to manage attacks and symptoms, and prevent relapses.

Every person with NMO is affected differently and some may have much milder symptoms than others. However, early treatment is usually needed to prevent further episodes and permanent disability.

Medication is used to reduce nerve inflammation, suppress the immune system and treat any pain. Rehabilitation techniques, such as physiotherapy, can also help with any reduced mobility that the relapses cause.

At these centres, research is ongoing to find possible future treatments for NMO.

To be referred to one of these centres, a GP referral letter is all that’s needed. These specialist services are nationally funded, so GP practices won’t have any additional costs for referring.

NMO UK has more information about treatments for NMO.

Driving

Optic neuritis (inflammation of the optic nerve) could affect your ability to drive.