Crohn’s disease, a debilitating inflammatory bowel disease, has long been known to have several contributing factors, including bacterial changes in the microbiome that foster an inflammatory environment. However, new research from Boston Children’s Hospital has uncovered a surprising link between Crohn’s disease and a virus—specifically, the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), best known for causing infectious mononucleosis (mono).

The Chicken and Egg Problem

Researchers had previously observed increased levels of EBV in the intestines of patients with Crohn’s disease and had found associations between EBV and other autoimmune diseases, such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. However, it was unclear which came first: EBV or Crohn’s disease. According to Anubhab Nandy, PhD, a research fellow in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Boston Children’s Hospital, “It was a classic chicken and egg problem.”

Longitudinal Study Findings

A recent longitudinal study published in Gastroenterology has provided strong evidence that EBV infection predisposes individuals to develop Crohn’s disease. Nandy and colleagues analyzed data from a cohort of initially healthy military recruits, aged 20 to 24, who provided periodic serum samples throughout their service. Using VirScan, a high-throughput assay developed by study coauthor Stephen Elledge, PhD, at Harvard Medical School, the researchers were able to detect antibodies against a wide range of viruses, offering insights into viral exposures.

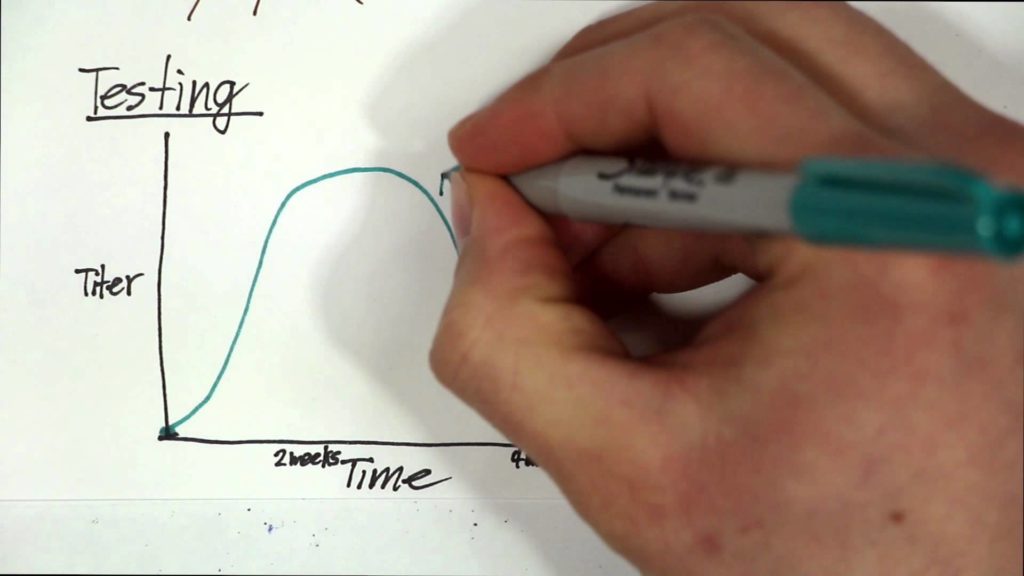

Compared with healthy controls, military personnel whose samples tested positive for anti-EBV antibodies were three times more likely to eventually develop Crohn’s disease. Intriguingly, evidence of EBV exposure preceded their Crohn’s diagnosis by five to seven years. “We went into this study not looking for EBV; we were looking for any virus that might elicit inflammatory bowel disease,” says Scott Snapper, MD, PhD, the study’s senior investigator and director of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at Boston Children’s. “Then, when EBV was a hit, we looked very specifically at immune responses to EBV with more detailed tests.”

Additional Insights

To further validate their findings, the team examined a second cohort of over 5,000 children (median age: 11 years) who were first-degree relatives of individuals with Crohn’s disease. In this cohort, EBV was not a statistically significant predictor of a subsequent Crohn’s disease diagnosis. Snapper speculates that having first-degree relatives with Crohn’s might already put these children at increased risk due to shared genetic or environmental factors, which could obscure the association with EBV.

EBV and the Immune System

Another possibility is that EBV affects children’s immune systems differently, as children are less likely to develop infectious mono when exposed. “Responding to certain organisms early in life may boost the immune system in a way that prevents immune-mediated disease,” Snapper explains.

Nandy and Snapper now aim to uncover the molecular mechanisms by which EBV increases susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. One hypothesis is that the virus has certain genes or molecules that interact with human genes involved in autoimmune susceptibility. Another possibility is related to an anti-inflammatory protein produced by EBV, which is remarkably similar to mammalian IL-10. Individuals exposed to this protein might produce antibodies against it, preventing their own IL-10 from working and making them susceptible to inflammatory disease.

Conclusion

“Mechanistically, we need to understand exactly how EBV alters the immune system leading to Crohn’s disease,” Snapper emphasizes. “If you could figure out the mechanisms, you could come up with new therapies.” This groundbreaking research not only highlights a surprising link between EBV and Crohn’s disease but also opens new avenues for understanding and potentially treating autoimmune conditions.