In talks at MIT, noted behavioral expert suggests encouraging skills of people with autism.

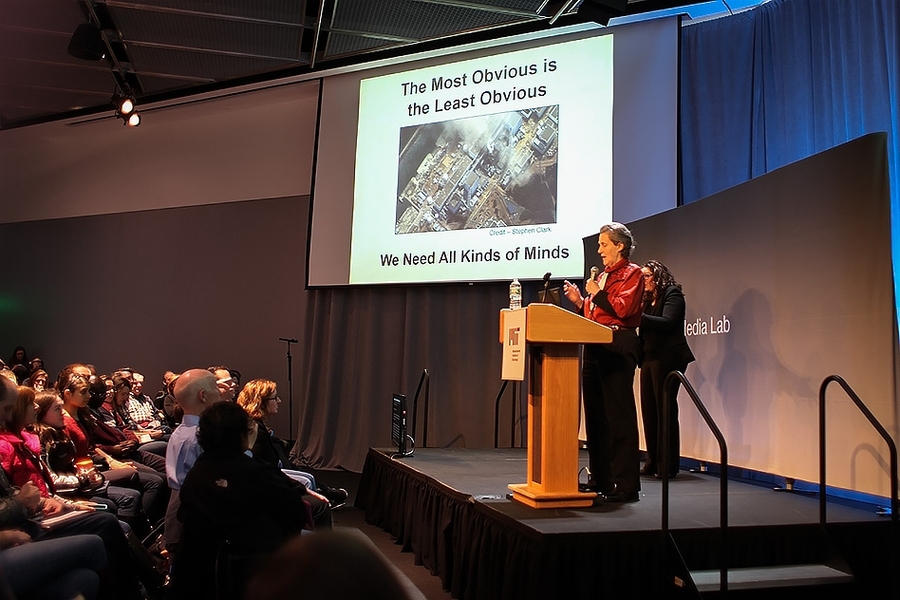

Caption:Temple Grandin speaks to a capacity crowd at the MIT Media Lab.Credits:Photo: Jose-Luis Olivares/MIT

Caption:Temple GrandinCredits:Photo: Maia Weinstock/MIT

When she was just two, doctors advised Temple Grandin’s mother that her child would probably need to be institutionalized for life due to her autism. But her mother would have none of that, and instead focused on teaching her daughter basic social and life skills, even though she didn’t begin to speak until age four.

That approach worked with dramatic success. Grandin went on to graduate from college, earn a PhD, design new systems for animal handling that revolutionized the meat processing industry, earn a faculty position at Colorado State University, and become a leading spokesperson and author on dealing with autism. In public talks on Monday and Tuesday, she shared her insights at MIT’s Media Laboratory.

“I see too many kids who aren’t learning the basics,” said Grandin, referring to skills such as interacting with people socially and making things with one’s hands. She strongly recommended that children on the autism spectrum be encouraged, coached, and instructed in basic skills and simple tasks that build useful self-discipline — “Walking dogs for neighbors, doing simple chores, shaking hands, having a paper route.”

As they grow into adulthood, she said, it’s useful to enter internships and other ways to try out different careers. “I thought I was going to be an experimental psychologist, I didn’t think I would be designing slaughterhouses,” she recalled.

But designing slaughterhouses has indeed been the basis of her career. Early on, as someone who had suffered intensely from anxiety attacks until those were controlled by low-dose, anti-anxiety medication, she noticed that the way cattle were traditionally led into slaughterhouses let the approaching animals see, hear, and smell the carnage just ahead. This often caused them to panic and thus made them more difficult to handle — which caused the release of fear and stress hormones into their bloodstream. The new, more humane systems she designed to replace these traditional designs are now used in about half of all U.S. and Canadian slaughterhouses. “I think that’s pretty good for someone who people thought was retarded,” she said.

As she has also described in her books, Grandin explained that she is a visual thinker. The key moment in her revolutionizing of cattle handling was when she crawled through the cattle chute herself, taking in the sights and sounds firsthand from the animal’s perspective — and seeing things that seemed obvious from that point of view, but had been overlooked by generations of designers of such facilities.

Time and again as people asked questions during her two appearances at MIT, she urged people to “be specific — I can’t deal with abstractions.” Before answering a vague question about how to help a child with autism, she wanted to know the details: How old is the child? What does he like to do? Does he talk? What are his interests?

Many people on the autism spectrum are fascinated by things that move, she said: cars, planes, trains. Such interests can become fixations that lead nowhere, she said, but they can also be channeled. If a child loves trains, parents or teachers could use trains as examples to teach math or other skills, or look at where the trains are going and study those places. “Broaden it out,” she said, but in a way that’s “still linked to that favorite thing.”

When she herself was in the third grade, she said, she had a fixation with drawing horses’ heads. Instead of trying to stop her, teachers encouraged her to broaden that interest and start drawing other things. That approach worked, and in the end those drawing skills became very useful as she began to design buildings.

When asked about the role of medications in treating autism, she said that “way too many medications are given out to little kids. On the other hand, careful, sensible use of medications” can be very effective. In her own case, she said that brain scans later in life revealed that her amygdala — a part of the brain that is responsible for fear reactions, among other things — is three times larger than normal, perhaps accounting for anxiety attacks that struck without warning through much of her early life, until they were controlled through medication.

To visualize what her life was like before the medications, she asked people to imagine that the building they were in — the Media Lab — contained 100 extremely venomous snakes, which mostly remained hidden but might suddenly appear in front of you without warning, at any moment. “That’s the way I was until I got antidepressants,” she said.

In offering guidance, she suggested, the key is not to be angry or overprotective, but to offer concrete instructions. As an example, she said when as a young child she lapped her ice cream off the plate at school, a teacher just picked up the plate and said, “You’re not a dog” — and the lesson was learned. Today, she said, “I see overprotection [of autistic children] on even the smallest tasks.”

She added that “people are always looking for magic breakthroughs. But it’s more like slogging on, one step at a time,” to master necessary skills. In general today, she said, “kids are not doing enough hands-on things.”

Grandin referred with contempt to the latest version of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, known as DSM-5, in which Asperger’s syndrome — a very mild and widespread form of autism — is eliminated as a separate diagnosis and instead is included within the autism spectrum. “DSM-5 is a mess,” she said, because it lumps together so many different conditions, from “people who can’t dress themselves,” to those who may be “presidents of companies in Silicon Valley.”

She pointed out that many people at places such as MIT likely fall on the high-functioning end of that spectrum, and may have extraordinary abilities in some areas, but a lack of skills in other areas, such as social and interpersonal relations — which may cause problems in situations such as job interviews. To counter that, she suggested, “When you’re a really weird geek, the way to sell yourself is to show them your skills. … How do you sell yourself? I did it by showing off my work.”

The defining characteristic of autism, she explained, is a very uneven set of skills and abilities. That’s true of everyone, but the discrepancies are more extreme in those with autism, who tend to be “very good at some things, and not good at something else.” For those working with students or family members with autism, Grandin said, it’s important both to provide instruction on basic skills that may be lacking, and to support and reinforce the person’s skills and interests.

Such people may need a bit of extra help or accommodation along the way, she added, such as leaving a bit more time than usual to wait for a response to a question. “I want to see kids that are different get good outcomes,” she said. “I’m getting worried about that quirky kid who gets shunted aside.”

They key thing, she said, is to “Look at what they can do, not what they can’t do.”