“Study links synaesthesia to autism,” BBC News reports. The news comes from the results of a small study that suggests that synaesthesia is more common in adults with autism (also known as autistic spectrum disorder).

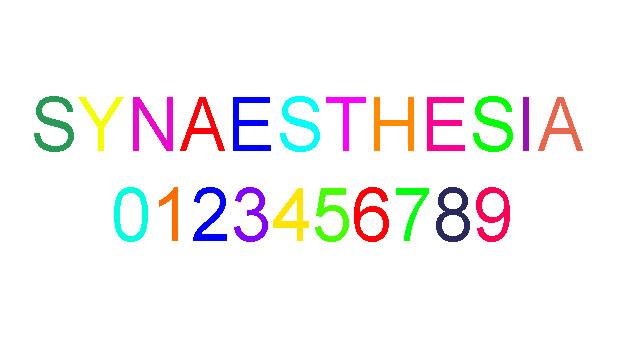

Synaesthesia is a condition where experiencing one sensation in one of the senses, such as hearing, involuntarily triggers another sensation in another sense, such as taste. An example given in the study for one person is that every time they heard the word “hello” they experienced the taste of coffee.

The researchers explain that synaesthesia has been estimated to affect around 4% of the population and autism 1% of the population. If the two phenomena were completely independent, you’d expect to see the same prevalence of synaesthesia in people with and without autism.

However, this study, which involved screening people with and without autism for synaesthesia, showed this may not be the case. In adults with autism, the prevalence of synaesthesia was estimated to be 18.9%, whereas adults without autism had a much lower prevalence of 7.21%.

The study’s results appear broadly reliable, but they need to be confirmed in larger studies to be sure. If true, these findings imply that the two conditions may share some common cause in the brain.

The researchers speculate that both conditions may be associated with what they term “hyperconnectivity”, or excessive neural connections between different parts of the brain.

Further research using technology such as functional MRI scanners may be able to provide more information about the biological link between the two conditions.

Where did the story come from?

The study was led by researchers from the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. The various collaborating authors involved in the work were funded by the National Institute for Health Research, the Gates Foundation, the Medical Research Council UK, and the Max Planck Society.

The study was published in the peer-reviewed science journal Molecular Autism.

BBC News’ reporting of the study was good quality. It provided an accurate overview of the research and included some useful quotes from the researchers involved as well as independent experts.

What kind of research was this?

This was a cross-sectional study looking at whether synaesthesia was more common in people with autism.

Synaesthesia is a condition where one sensation triggers a perception of a second. For example, a person could taste numbers or hear colours. Self-reported examples of this from the study include how “the letter q is dark brown”, “the sound of the bell is red”, and “the word hello tastes like coffee”.

Autism is shorthand for autistic spectrum conditions, which are a range of related developmental disorders, including autism and Asperger’s syndrome. They share some features, such as difficulties with social communication, resistance to change, and a focus on an unusually narrow range of interests or activities, but the level of difficulties faced varies between individuals.

People with Asperger’s syndrome have fewer problems with language, are often of average or above-average intelligence, and are usually high functioning and able to live independently.

Some people, the researchers report, have suggested that synaesthesia and autistic spectrum conditions may originate from brain abnormalities common across both conditions. This led the researchers to investigate whether synaesthesia was more common in people with autism to see if the two conditions appeared to be related.

A cross-sectional study is an appropriate way of assessing the prevalence of something in a group of people, such as estimating what proportion of people with autism experience synaesthesia. However, this type of study cannot prove that the two conditions are biologically linked.

What did the research involve?

A group of 927 adults with autism and 1,364 adults without autism were invited to participate in the study. Of these, 164 adults with clinically diagnosed autism and 97 adults without the condition took part.

Both groups completed online questionnaires assessing any experiences of synaethesia, as well as their autistic traits to check on the original autism diagnosis.

A third test was used to investigate the consistency of the participants’ synaesthetic experiences and to further check that they were reporting genuine experiences. This consistency test involved “matching” words or sounds to preferred colours.

Conservative inclusion criteria were reported to be used to judge if an individual had synaesthesia. For example, if synaesthesia was first experienced in adulthood, the person was judged not to have synaesthesia.

To be considered synaesthetic, participants had to report that they experienced synaesthesia and could not meet any of the exclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria included people who had medical conditions affecting their vision, the brain, or who had a history of hallucinogenic drug use. This was to ensure that their synaesthetic experiences were not as a result of injury or drug use.

The analysis compared the prevalence of synaethesia in people with autism with people without the condition.

What were the basic results?

Of the 164 people in the autism group, 31 were considered synaesthetic, a rate of 18.9%. Synaesthesia in the control group was significantly lower, at 7 out of of 97 people, or 7.21%.

Most of the autism group had Asperger’s syndrome (03%), nine (5.5%) had higher-functioning autism, and two (1.2%) had pervasive developmental disorder (not otherwise specified).

No group differences were found in age or education, with the latter measured by the rate of university attendance.

Hardly anyone filled in the consistency questionnaire, so it was not possible for the researchers to obtain results from this. Further investigation revealed that people with autism were fatigued from the 241 possible choices during this test, so gave up before completing it.

How did the researchers interpret the results?

The researchers concluded that, “The significant increase in synaesthesia prevalence in autism suggests that the two conditions may share some common underlying mechanisms. Future research is needed to develop more feasible validation methods of synaesthesia in autism.”

Conclusion

This small study suggests that synaethesia is more common in adults with autism than in adults who do not have the condition. Prevalence in a group mainly diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome was estimated at 18.9%, compared with 7.21% in adults without autism, using a sample of 261 people in total.

In spite of these interesting findings, the study has several limitations:

- The study sample was relatively small for a prevalence study. A study using more people would produce more reliable estimates and would be able to confirm or refute these initial findings.

- The study participants with an autistic spectrum disorder mainly had Asperger’s syndrome, which is at the higher functioning end of the spectrum, with only two people having potentially greater impairment. The results cannot be generalised to all people with autism.

- The researchers were unable to collect completed consistency tests to validate the prevalence estimates of synaesthesia. They report that the traditional test to confirm symptoms may not be suitable for people with autism.

- The study did not recruit children, so it is not clear if similar findings would be discovered earlier in life.

- It is not clear how representative the “control” group of adults without a diagnosis of an autistic spectrum disorder was of the general population. It was a small sample size, and it is not clear what their motivations were for completing the questionnaires. What is interesting is that 27 respondents without a formal diagnosis of autism were excluded from the study because their answers to the autism questionnaire indicated that they might be on the spectrum.

- The criteria for assessing whether someone was synaesthetic or not weren’t wholly clear. Using a stricter or looser definition to categorise synaesthesia would change the estimates of prevalence reported.

- The study does not tell us about the biological underpinnings of synaesthesia or what they may or may not have in common with autism.

- The study didn’t seem to account for the possibility that some people with psychosis might report experiences that could be falsely categorised as synaesthetic. However, the impact of this possibility is likely to be very small.

In considering the results, it is important to realise that synaesthesia is not necessarily an impairment and in some cases can enhance memory or creativity.

The bottom line is that this study suggests synaesthesia is more prevalent in adults with autism than non-autistic adults, but this needs to be confirmed in bigger studies to be more certain.

If true, the implication of this finding is that the two conditions may share some common causes in the brain, but this is not yet proven.

The researchers argue that investigation into the possible links between the two conditions using more sophisticated techniques such as MRI scans is now a research priority.

Analysis by Bazian

Edited by NHS Website