Chorionic villus sampling (CVS) is a test you may be offered during pregnancy to check if your baby has a genetic or chromosomal condition, such as Down’s, Edwards’ or Patau’s syndromes.

It involves removing and testing a small sample of cells from the placenta (the organ linking the mother’s blood supply with her unborn baby’s).

When CVS is offered

CVS isn’t routinely offered to all pregnant women. It’s only offered if there’s a high risk your baby could have a genetic or chromosomal condition.

This could be because:

an earlier antenatal screening test has suggested there may be a problem, such as Down’s syndrome, Edwards’ syndrome or Patau’s syndrome

you’ve had a previous pregnancy with these problems

you have a family history of a genetic condition, such as sickle cell disease, thalassaemia, cystic fibrosis or muscular dystrophy, and an abnormality is detected in your baby during a routine ultrasound scan

It’s important to remember that you don’t have to have CVS if it’s offered. It’s up to you to decide whether you want it.

Your midwife or doctor will speak to you about what the test involves, and let you know what the possible benefits and risks are, to help you make a decision.

Read more about why CVS is offered and deciding whether to have it.

How CVS is performed

CVS is usually carried out between the 11th and 14th weeks of pregnancy, although it’s sometimes performed later than this if necessary.

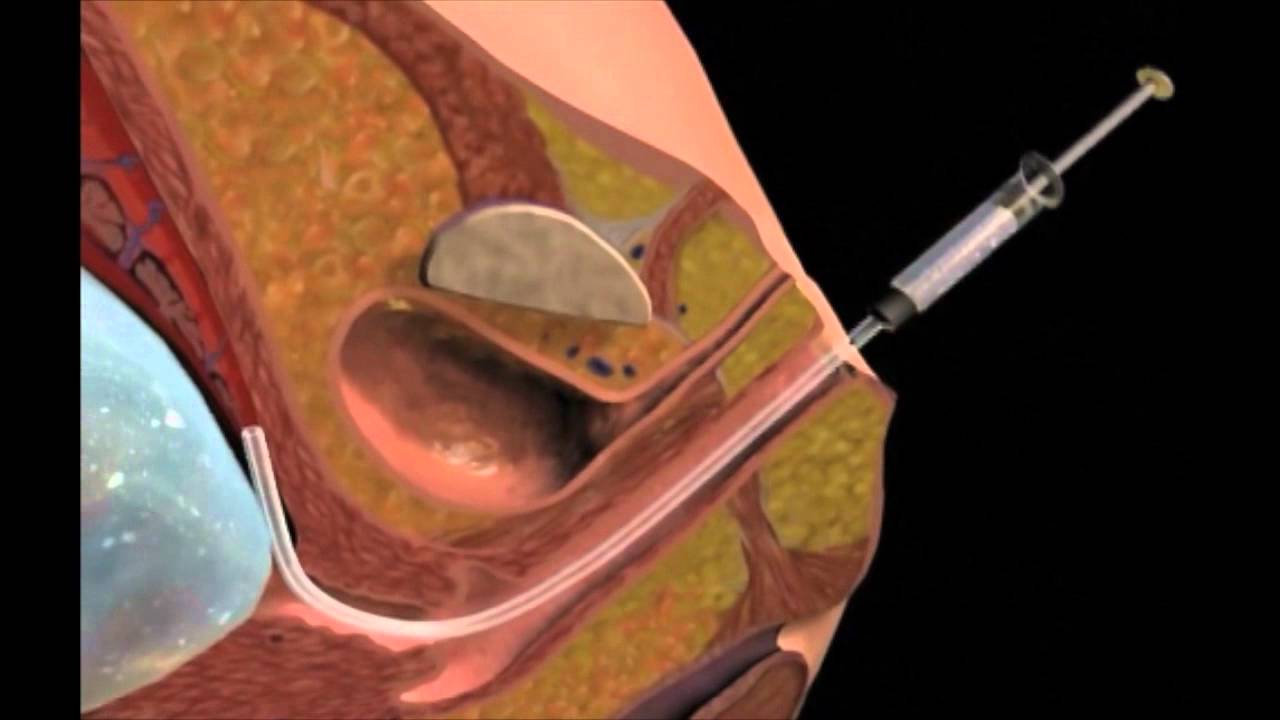

During the test, a small sample of cells will be removed from the placenta using one of two methods:

transabdominal CVS – a needle is inserted through your tummy (this is the most common method used)

transcervical CVS – a tube or small forceps (smooth metal instruments that look like tongs) are inserted through the cervix (the neck of the womb)

The test itself takes about 10 minutes, although the whole consultation may take about 30 minutes.

The CVS procedure is usually described as being uncomfortable rather than painful, although you may experience some cramps that are similar to period pains for a day or two afterwards.

Read more about what happens during CVS.

Getting your results

The first results of the test should be available within three working days and this will tell you whether a major chromosome condition, such as Down’s, Edwards’ or Patau’s syndrome, has been discovered.

If rarer conditions are also being tested for, it can take two to three weeks or more for the results to come back.

If your test shows that your baby has a genetic or chromosomal condition, the implications will be fully discussed with you. There’s no cure for most of the conditions CVS finds, so you’ll need to consider your options carefully.

You may choose to continue with your pregnancy, while gathering information about the condition so you’re fully prepared, or you may consider having a termination (abortion).

Read more about the results of CVS.

What are the risks of CVS?

Before you decide to have CVS, the risks and possible complications will be discussed with you.

One of the main risks associated with CVS is miscarriage, which is the loss of the pregnancy in the first 23 weeks. This is estimated to occur in 0.5% to 1% of women who have CVS.

There are also some other risks, such as infection or needing to have the procedure again because it wasn’t possible to accurately test the first sample that was removed.

The risk of CVS causing complications is higher if it’s carried out before the 10th week of pregnancy, which is why the test is only carried out after this point.

Read more about the risks of CVS.

What are the alternatives?

An alternative to CVS is a test called amniocentesis. This is where a small sample of amniotic fluid (the fluid that surrounds the baby in the womb) is removed for testing.

It’s usually carried out between the 15th and 18th week of pregnancy, although it can be performed later than this if necessary.

This test has a similar risk of causing a miscarriage, but your pregnancy will be at a more advanced stage before you can get the results, so you’ll have a bit less time to consider your options.

If you’re offered tests to look for a genetic or chromosomal condition in your baby, a specialist involved in carrying out the test will be able to discuss the different options with you, and help you make a decision.