Dr. Mercedes Alfonso-Prieto from the Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Forschungszentrum Jülich CREDIT Forschungszentrum Jülich / Ralf-Uwe Limbach

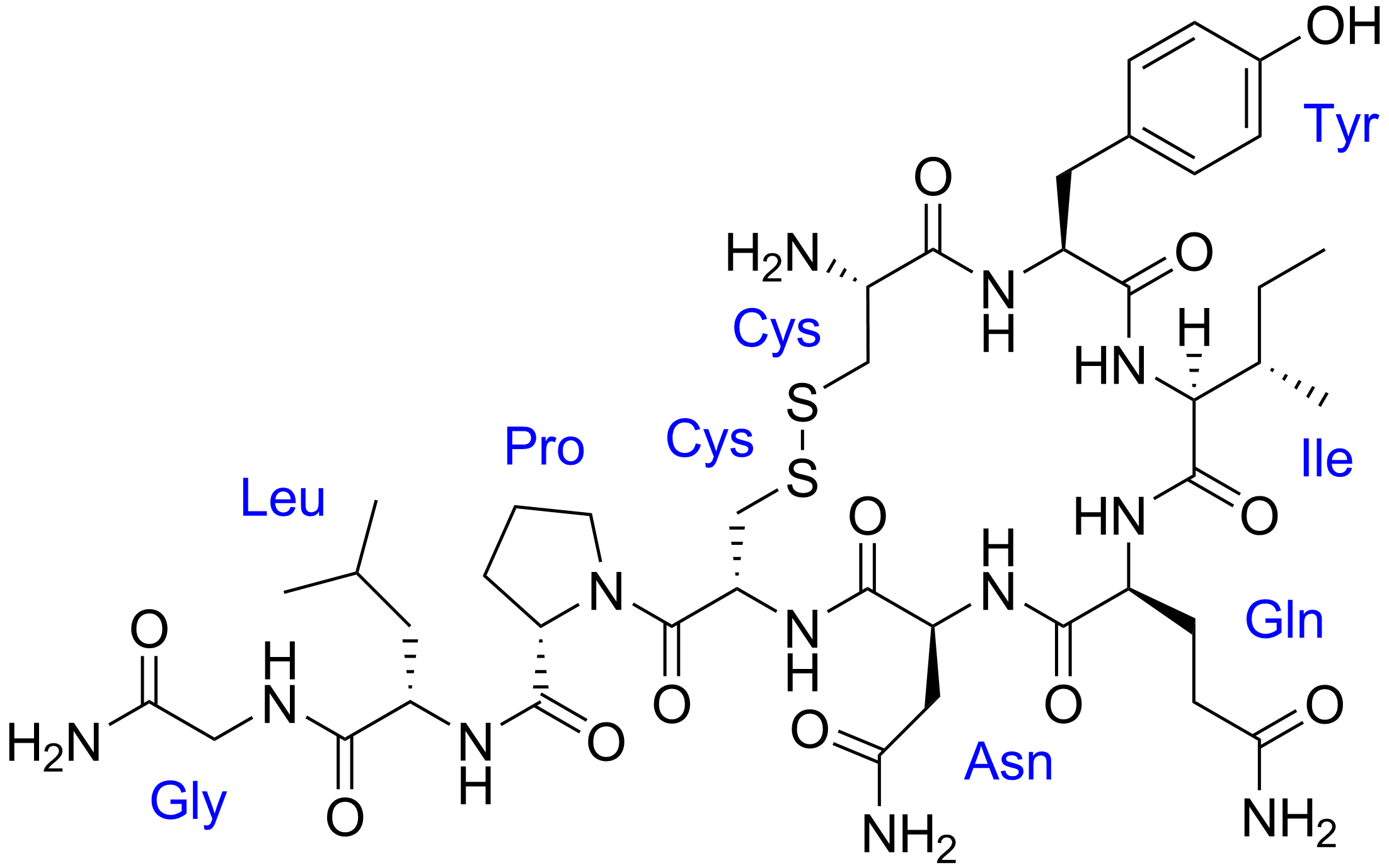

Oxytocin is known as the “love hormone”. It strengthens social bonding and promotes trust and empathy. These behavioral traits are caused by the binding of the hormone to the oxytocin receptor in the brain. Researchers at the University of Regensburg and Forschungszentrum Jülich have now demonstrated, with the help of cell culture experiments and computer simulations, how genetic variations of the receptor affect the hormone signaling inside brain cells. Their findings provide a better understanding why nasal sprays with oxytocin are not always helpful to treat autistic patients and they point to alternative strategies that could lead to new therapies in the long term.

Changes in the finely tuned mechanism of oxytocin interacting with its receptor might trigger psychosocial disorders. Researchers have been assuming this for a long time. In fact, genetic variants of the oxytocin receptor have already been associated with autism spectrum disorder. However, the causal mechanisms linking these mutations to the onset of autism are still unknown.

Structure of the oxytocin receptor (left) and the mutant receptor variant A218T (right) CREDIT Forschungszentrum Jülich / Mercedes Alfonso-Prieto

There are some indications that there is more than one single cause. As a consequence, the simple use of nasal sprays with oxytocin helps only in certain cases to improve social interaction in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Various studies on therapeutic effects, conducted for example by researchers at Forschungszentrum Jülich ( DOI: 10.1038/s41386-018-0258-7) or recently published by US researchers in the New England Journal of Medicine in October (DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103583), obtained quite different results, with the treatment efficacy being highly variable among patients. But without the knowledge of the molecular mechanism that causes oxytocin nasal sprays to work only in some patients, an effective, standardized treatment is unattainable.

In a recent work, together with partners from the University of Regensburg, researchers at the Jülich Institute for Neuroscience and Medicine (INM-9/IAS-5) have now described in detail how a specific variant in the DNA sequence of the oxytocin receptor affect the hormone-triggered response of the neurons.

“The devil really is in the detail here,” explains Dr. Mercedes Alfonso-Prieto. “The oxytocin receptor consists of 389 amino acids. The variant we studied deviates from the normal type in only one – a rather subtle change, but one that is amplified inside the cell as if by a kind of domino effect.”

Together with colleagues at her institute, led by Prof. Paolo Carloni, she modelled and simulated the effect of the mutation. “We focused on understanding the mechanism of how the structure of the oxytocin receptor is changed and how this affects the subsequent cellular response,” explains Mercedes Alfonso-Prieto.

The surprising result: the mutated variant is more active and stable than the normal receptor, contrary to what might intuitively be expected.

„Despite its connection to autism, we were puzzled that the receptor variant had been previously classified as non-pathogenic“, say Dr. Magdalena Meyer and Dr. Benjamin Jurek from the University of Regensburg, who studied the cell response to oxytocin experimentally in the laboratory. The Regensburg working group, led by Prof. Inga Neumann, has been researching the neurobiological effects of oxytocin for many years. The current work in the prestigious journal Molecular Psychiatry now provides new starting points for developing new therapies in the long term.

“Since the mutant variant reacts excessively to oxytocin, increasing the oxytocin level by means of a nasal spray is probably not the best therapeutic strategy for treating autistic patients with this mutation,” explains Magdalena Meyer. More success is promised by drug development approaches that aim to find molecules that can restore the normal response levels of the receptor.