Acute cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis is swelling (inflammation) of the gallbladder. It is a potentially serious condition that usually needs to be treated in hospital.

The main symptom of acute cholecystitis is a sudden sharp pain in the upper right side of your tummy (abdomen) that spreads towards your right shoulder.

The affected part of the abdomen is usually extremely tender, and breathing deeply can make the pain worse.

Unlike some others types of abdominal pain, the pain associated with acute cholecystitis is usually persistent, and doesn’t go away within a few hours.

Some people may additional symptoms, such as:

- a high temperature (fever)

- nausea and vomiting

- sweating

- loss of appetite

- yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes (jaundice)

- a bulge in the abdomen

When to seek medical advice

You should see your GP as soon as possible if you develop sudden and severe abdominal pain, particularly if the pain lasts longer than a few hours or is accompanied by other symptoms, such as jaundice and a fever.

If it’s not possible to contact your GP immediately, phone your local out-of-hours service or call NHS 111 for advice.

It’s important for acute cholecystitis to be diagnosed as soon as possible, because there is a risk that serious complications could develop if the condition is not treated promptly (see below).

What causes acute cholecystitis?

The causes of acute cholecystitis can be grouped into two main categories: calculous cholecystitis and acalculous cholecystitis.

Calculous cholecystitis

Calculous cholecystitis is the most common, and usually less serious, type of acute cholecystitis. It accounts for around 95% of all cases.

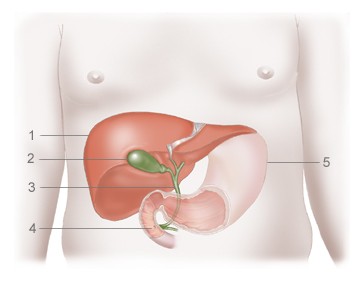

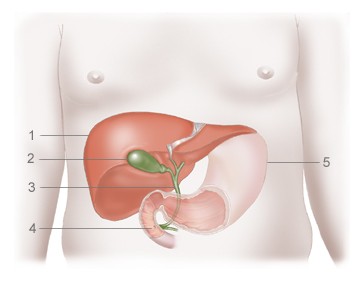

Calculous cholecystitis develops when the main opening to the gallbladder, called the cystic duct, gets blocked by a gallstone or by a substance known as biliary sludge.

Biliary sludge is a mixture of bile (a liquid produced by the liver that helps digest fats) and small crystals of cholesterol and salt.

The blockage in the cystic duct results in a build-up of bile in the gallbladder, increasing the pressure inside it and causing it to become inflamed. In around one in every five cases, the inflamed gallbladder also becomes infected by bacteria.

Acalculous cholecystitis

Acalculous cholecystitis is a less common, but usually more serious, type of acute cholecystitis. It usually develops as a complication of a serious illness, infection or injury that damages the gallbladder.

Acalculous cholecystitis is often associated with problems such as accidental damage to the gallbladder during major surgery, serious injuries or burns, blood poisoning (sepsis), severe malnutrition or AIDS.

Who is affected

Acute cholecystitis is a relatively common complication of gallstones.

It is estimated that around 10-15% of adults in the UK have gallstones. These don’t usually cause any symptoms, but in a small proportion of people they can cause infrequent episodes of pain (known as biliary colic) or acute cholecystitis.

In England, around 28,000 cases of cholecystitis were reported during 2012-13.

Diagnosing cholecystitis

To diagnose acute cholecystitis, your GP will examine your abdomen.

They will probably carry out a simple test called Murphy’s sign. You will be asked to breathe in deeply with your GP’s hand pressed on your tummy, just below your rib cage.

Your gallbladder will move downwards as your breathe in and, if you have cholecystitis, you will experience sudden pain as your gallbladder reaches your doctor’s hand.

If your symptoms suggest you have acute cholecystitis, your GP will refer you to hospital immediately for further tests and treatment.

Tests you may have in hospital include:

- blood tests to check for signs of inflammation in your body

- an ultrasound scan of your abdomen to check for gallstones or other signs of a problem with your gallbladder

Other scans – such as an X-ray, a computerised tomography (CT) scan or a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan – may also be carried out to examine your gallbladder in more detail if there is any uncertainty about your diagnosis.

Treating acute cholecystitis

If you are diagnosed with acute cholecystitis, you will probably need to be admitted to hospital for treatment.

Initial treatment

Initial treatment will usually involve:

- fasting (not eating or drinking) to take the strain off your gallbladder

- receiving fluids through a drip directly into a vein (intravenously) to prevent dehydration

- taking medication to relieve your pain

If you have a suspected infection, you will also be given antibiotics. These often need to be continued for up to a week, during which time you may need to stay in hospital or you may be able to go home.

With this initial treatment, any gallstones that may have caused the condition usually fall back into the gallbladder and the inflammation often settles down.

Surgery

In order to prevent acute cholecystitis recurring, and reduce your risk of developing potentially serious complications, the removal of your gallbladder will often be recommended at some point after the initial treatment. This type of surgery is known as a cholecystectomy.

Although uncommon, an alternative procedure called a percutaneous cholecystostomy may be carried out if you are too unwell to have surgery. This is where a needle is inserted through your abdomen to drain away the fluid that has built up in the gallbladder.

If you are fit enough to have surgery, your doctors will need to decide when the best time to remove your gallbladder may be. In some cases, you may need to have surgery immediately or in the next day or two, while in other cases you may be advised to wait for the inflammation to fully resolve over the next few weeks.

Surgery can be carried out in two main ways:

- laparoscopic cholecystectomy – a type of keyhole surgery where the gallbladder is removed using special surgical instruments inserted through a number of small cuts (incisions) in your abdomen

- open cholecystectomy – where the gallbladder is removed through a single, larger incision in your abdomen

Although some people who have had their gallbladder removed have reported symptoms of bloating and diarrhoea after eating certain foods, you can lead a perfectly normal life without a gallbladder.

The organ can be useful but it’s not essential, as your liver will still produce bile to digest food.

Read more about recovering from gallbladder removal.

Possible complications

Without appropriate treatment, acute cholecystitis can sometimes lead to potentially life-threatening complications.

The main complications of acute cholecystitis are:

- the death of the tissue of the gallbladder, called gangrenous cholecystitis, which can cause a serious infection that could spread throughout the body

- the gallbladder splitting open, known as a perforated gallbladder, which can spread the infection within your abdomen (peritonitis) or lead to a build-up of pus (abscess)

In about one in every five cases of acute cholecystitis, emergency surgery to remove the gallbladder is needed to treat these complications.

Preventing acute cholecystitis

It’s not always possible to prevent acute cholecystitis, but you can reduce your risk of developing the condition by cutting your risk of gallstones.

One of the main steps you can take to help lower your chances of developing gallstones is adopting a healthy, balanced diet and reducing the number of high-cholesterol foods you eat, as cholesterol is thought to contribute to the formation of gallstones.

Being overweight, particularly being obese, also increases your risk of developing gallstones. You should therefore control your weight by eating a healthy diet and exercising regularly.

However, low-calorie, rapid weight loss diets should be avoided, because there is evidence they can disrupt your bile chemistry and actually increase your risk of developing gallstones. A more gradual weight loss plan is best.

Read more about preventing gallstones.

[Original article on NHS Choices website]