In a groundbreaking step toward combating serious illnesses linked to the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a spin-off from Helmholtz Munich called EBViously officially launched on 11 November 2024. The company is on a mission to develop a vaccine that could prevent a wide range of diseases, including infectious mononucleosis, certain cancers, chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), and, most notably, multiple sclerosis (MS)—a devastating autoimmune disease of the nervous system.

Why Target EBV?

Epstein-Barr virus, part of the herpes virus family, is one of the most common viruses in the world, with an estimated 90% of the global population infected. While infections during early childhood are usually mild, later infections can lead to mononucleosis (“mono”) and set the stage for long-term complications like ME/CFS and MS.

Recent research has identified EBV as the leading risk factor for MS. In this condition, the immune system mistakenly attacks the nervous system, causing symptoms like fatigue, vision problems, and mobility issues. By preventing EBV infections, EBViously’s vaccine has the potential to dramatically reduce the risk of developing MS.

An Innovative Vaccine

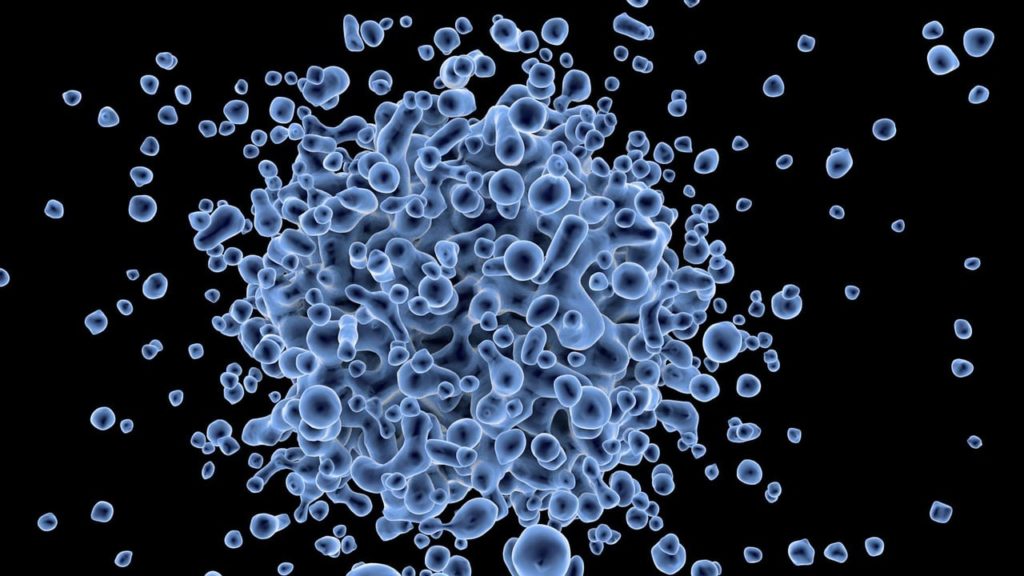

EBViously’s vaccine candidate, EBV-001, is built on cutting-edge technology using virus-like particles (VLPs). These particles mimic the Epstein-Barr virus’s structure but contain no viral genetic material, making them non-infectious. This design “tricks” the immune system into launching a defense against EBV without exposing the body to the actual virus.

Preclinical studies in animal models have shown highly promising results, with the vaccine successfully triggering targeted immune responses. According to Prof. Wolfgang Hammerschmidt of Helmholtz Munich, “Our approach pulls the virus’s teeth while preserving its protein combinations, ensuring the immune system is well-prepared to combat EBV.”

Hope for MS and Beyond

The vaccine’s benefits could go far beyond protecting against mono. By stopping EBV infections in their tracks, the vaccine could also help prevent secondary diseases like ME/CFS, reduce the risk of EBV-associated cancers (including lymphomas), and even protect transplant patients from post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease. Most significantly, it could lower the risk of developing multiple sclerosis, offering hope to millions who live with or are at risk of this chronic condition.

Fast-Tracking Clinical Trials

With approximately 12 million euros in funding so far, including support from the Helmholtz Validation Fund and DZIF, EBViously is pushing to bring its vaccine to clinical trials as quickly as possible. The vaccine is being developed and manufactured under stringent Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) standards in collaboration with prestigious partners like Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich and TUM University Hospital.

Dr. Sebastian Goy, CEO of EBViously, emphasizes the urgency of the mission: “The founding of EBViously is a major step toward accelerating the clinical development of EBV-001. We are optimistic that this vaccine will protect millions worldwide from serious diseases caused by EBV, including multiple sclerosis.”

A Vision for the Future

With plans to secure additional investors, EBViously is racing toward the goal of making EBV-001 a reality. If successful, this vaccine could not only transform the way we think about MS prevention but also mark a new era in the fight against EBV-related diseases.

For those at risk of MS and other debilitating conditions, EBViously represents more than a vaccine—it’s a symbol of hope for a healthier, brighter future.