Brugada syndrome is an uncommon, but serious, heart condition. It can result in abnormally rapid heart rhythms called arrhythmias, which can cause palpitations or fainting and can be fatal.

However, some people with the condition have no symptoms at all.

Even though the heart pumps and looks normal, it’s possible for sudden electrical activity to lead to a dangerous heart rhythm.

This problem can be genetic, or may be passed on in families – see What’s the cause? below.

Not everyone with Brugada syndrome experiences arrhythmia, but when it does happen, it can be fatal.

What are the signs and symptoms of Brugada syndrome?

Often, there are no warning signs of Brugada syndrome until an abnormal heart rhythm causes the heart to stop beating (cardiac arrest).

Some people may experience symptoms such as:

blackouts

seizures

(sometimes) heart palpitations

A family history of Brugada syndrome or unexplained sudden deaths may also be a warning sign.

Around a fifth of people with Brugada syndrome also experience atrial fibrillation, a heart condition that causes an irregular and abnormally fast heart rate.

Having a high temperature (fever) is thought to increase the risk of symptoms appearing or can aggravate existing symptoms.

How can it be fatal?

Sometimes the abnormal heart rhythm persists, leading to ventricular fibrillation, a rapid, uncoordinated series of heart contractions.

Most of the time, this doesn’t revert to normal heart rhythm without being corrected electrically, and usually causes the heart to stop pumping.

Brugada syndrome is a leading cause of sudden cardiac death in young, otherwise healthy people and may not be diagnosed because there’s no visible abnormality.

It may explain some cases of sudden infant death syndrome, which is a major cause of death in babies younger than one.

Sadly, most deaths from Brugada syndrome happen without any warning sign of the disorder.

Who’s affected

Brugada syndrome typically affects young and middle-aged males who are otherwise healthy, although women can also be affected.

It’s also more common in young men of Japanese and south east Asian descent. Read more about South Asian health.

Men are more likely than women to show signs of it, possibly because of the sex hormone testosterone, which is thought to play a role.

What is the underlying cause of Brugada syndrome?

The heart of someone with Brugada syndrome is structurally normal, but there are problems with electrical activity.

To properly understand the underlying cause, it’s important to know how the heart cells work.

On the surface of each heart muscle cell are tiny pores, or ion channels. These open and close to let electrically charged sodium, calcium and potassium atoms (ions) flow into and out of the cells.

This passage of ions generates the heart’s electrical activity. An electrical signal spreads from the top of the heart to the bottom, causing the heart to contract and pump blood.

More information on how the heart works can be found at the bottom of this page.

Genetic mutation

There are many different genetic mutations that have been linked to Brugada syndrome. The SCN5A gene is most often involved, but only in around a third of cases.

This particular gene provides instructions for making a sodium channel that transports positively charged sodium ions into heart muscle cells.

The mutation in this gene affects the proteins that make up the sodium channels, so they don’t work as well. There’s a reduced flow of sodium ions into the heart cells, which alters the way the heart beats.

Only one copy of the altered gene in each cell is needed to cause the disorder. In most cases, an affected person has just one parent with the condition.

Not all people with Brugada syndrome have these common gene mutations and there isn’t always a family history of it.

Other genes may be involved, and there can be many factors contributing to the development of symptoms, including medicines and imbalances of salts in the body.

How is it diagnosed?

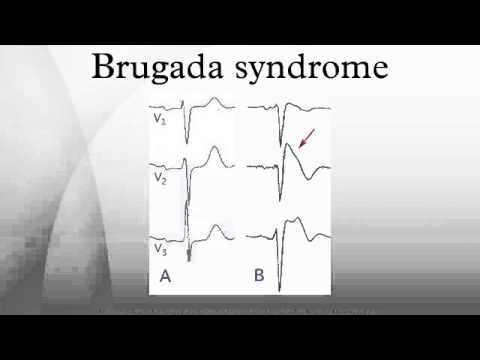

If your GP thinks you have Brugada syndrome after assessing your symptoms, they may ask you to have an electrocardiogram (ECG) and refer you to a heart specialist (cardiologist). This should usually be a cardiologist who specialises in heart rhythm and genetic heart problems.

ECG

An ECG is a test that records the rhythm and electrical activity of your heart. Every time your heart beats, it produces tiny electrical signals, which an ECG machine traces on to paper.

Small stickers called electrodes are stuck on to your arms, legs and chest and connected by wires to the ECG machine.

If Brugada syndrome is suspected, you’ll probably have a simple and safe test known as an ajmaline or flecainide challenge to confirm your diagnosis.

Ajmaline and flecainide are antiarrhythmic medicines that correct abnormal heart rhythms, which block sodium channels.

The medicine is given through a vein in your arm, and an ECG records how your heart responds to it.

If given to someone with Brugada syndrome, it can reveal the abnormal ECG pattern characteristic of the syndrome.

Other antiarrhythmic medicines, such as propafenone or procainamide, can also reveal an irregular ECG result and lead to a diagnosis of Brugada syndrome.

If the test is negative, your doctor will consider your individual risk of having the syndrome and advise if further tests are needed, but you’ll probably be able to go home the same day.

You may need to have an echocardiography or MRI scan to rule out other heart problems and causes of arrhythmia, and blood tests to measure blood potassium and calcium levels.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing may also be carried out to identify the defective SCN5A gene that may be causing Brugada syndrome.

You and your family may be offered genetic testing if Brugada syndrome is diagnosed in a relative.

Learn more about genetic testing.

How is it treated?

The only proven effective treatment for Brugada syndrome is having an implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) fitted.

An ICD is similar to a pacemaker. If the ICD senses your heart is beating at a potentially dangerous abnormal rate, it can deliver treatment, such as an electrical shock, to help return your heart to a normal rhythm and pumping correctly.

An ICD won’t prevent arrhythmia, but it can treat it if it happens and help prevent sudden cardiac death.

Find out how an ICD is fitted.

There are currently no medicines recommended to treat Brugada syndrome.

A few simple measures can help prevent heart rhythm disturbances. For example, you can avoid getting a high temperature (fever) by taking paracetamol, and should treat illnesses like diarrhoea, which can affect the balance of salts in the body.