“The NHS spends £25 million on acupuncture each year despite experts saying there is ‘insufficient’ evidence it helps fight pain,” reports the Mail Online.

This is arguably quite a one-sided headline as it has been prompted by two opinion pieces in the peer-reviewed BMJ, in which a supporter of acupuncture, and two critics of the practice, argue their respective cases.

One researcher from the British Medical Acupuncture Society feels acupuncture is a safe alternative to drugs and is under-researched because of a lack of commercial interest. However, two researchers from the University of Southern Denmark argue there is no convincing evidence of clinical benefit and, because of this, potential risks of the procedure and health services costs are unjustified.

To summarise, evidence outlining the benefits of acupuncture does exist, but it is not strong evidence. There are also concerns the positive effects found in acupuncture research are only small and, arguably, due to a placebo effect. Participants know when they are receiving it (it is an unblinded intervention). Also few research studies compare acupuncture to usual care or other interventions. Acupuncture treatment for lower back pain was removed from the NICE guidelines in the 2016 update because there was not reliable evidence that it was any better than sham acupuncture (which uses blunt needles).

NICE guidelines still recommend acupuncture for chronic tension-type headaches and migraines.

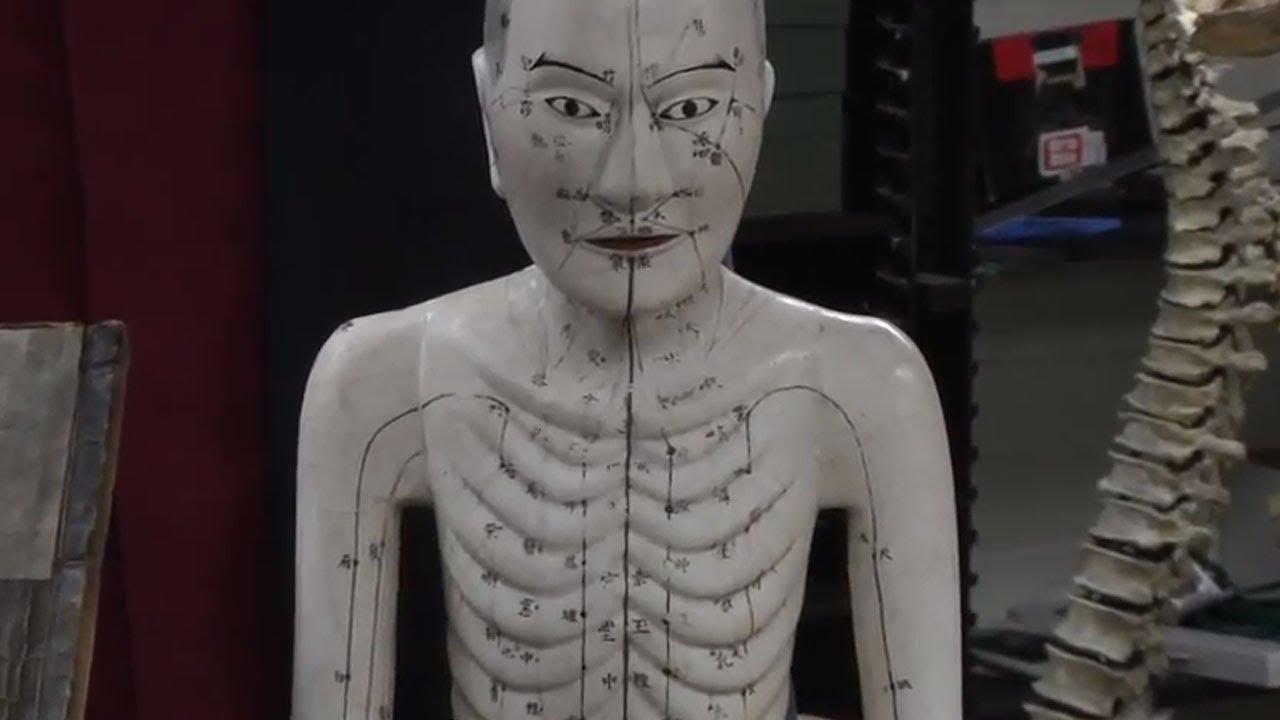

What is acupuncture?

Acupuncture is a complementary medicine technique originating from ancient Chinese medicine. It uses fine needles that are inserted into the skin at specific points, along what are considered to be lines of energy.

It is used for both the treatment of physical and mental conditions and has been used in a lot of NHS general practices and pain clinics in the UK.

While acupuncture is sometimes available on the NHS, most acupuncture patients pay for private treatment. Although NICE only recommends considering acupuncture as a treatment option for chronic tension-type headaches and migraines, it is also often used to treat other musculoskeletal conditions, including chronic pain, joint pain, dental pain and postoperative pain.

In many of the conditions where acupuncture is used, there is limited good-quality evidence to draw any clear conclusions over its effectiveness compared with other treatments.

What is the basis for these current reports?

Many doctors in developed countries recommend acupuncture for treating pain, but the UK is narrowing its availability as an NHS-funded treatment. The medical director of the British Medical Acupuncture Society thinks the removal of acupuncture from NICE guidelines was due to a misinterpretation of the evidence. He further points out that while NICE guidelines recommend drugs before acupuncture for migraines, a Cochrane review reports acupuncture is better. Cochrane reviews involve researchers looking at the data from a number of relevant studies.

The largest study supporting the use of acupuncture for chronic pain used individual patient data from 20,827 patients. This study showed a moderate benefit for acupuncture compared with usual care, and smaller effects were found for sham acupuncture. However, this study did not compare acupuncture to other interventions. Doing so would have made its findings more credible.

In terms of NHS resources, acupuncture requires more medical staff and infrastructure than drug-based treatments. For those patients who respond well, acupuncture has a lower long-term risk than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. It may also be useful for chronic pain in older patients who are particularly at risk from adverse drug reactions.

The two professors from the University of Denmark are less positive about the small beneficial effects of acupuncture. They feel after decades of research, there is still no strong, clear evidence for the benefits of acupuncture, or enough information about the possible harms of this treatment. Although regarded as harmless, acupuncture can cause pain, haemorrhages, infection, pneumothorax (collapsed lung), and even death. It is argued that taxpayers’ money could be better used for interventions proven to be effective.

How might this affect you?

A single opinion piece is unlikely to change NHS guidelines on providing acupuncture, so we doubt these will change in the near future.

But a reality is that NHS provision of acupuncture is limited. Most acupuncture patients pay for private treatment. The cost of acupuncture varies widely between practitioners. At the time of writing, initial sessions usually cost £40-70, and further sessions £25-60.

This interesting debate piece is unlikely to change the minds of supporters or critics of acupuncture. But it does possibly highlight the need for more robust and, ideally blinded, trials into the effectiveness of acupuncture.