Acromegaly is a condition in which the body produces too much growth hormone, leading to the excess growth of body tissues over time.

Typical features include:

- abnormally large hands and feet

- large, prominent facial features

- an enlarged tongue

- abnormally tall height (if it occurs before puberty)

Growth hormone is produced and released by the pituitary gland, a pea-sized gland just below the brain.

When growth hormone is released into the blood, it stimulates the liver to produce another hormone – insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) – which causes growth of muscle, bones and cartilage throughout the body.

This process is essential for growth and repair of body tissues.

What happens in people with acromegaly?

Acromegaly is caused by excessive production of growth hormone.

This usually occurs as the result of a benign (non-cancerous) brain tumour in the pituitary gland called an adenoma, but rare cases have been linked to tumours elsewhere in the body, such as in the lungs and pancreas.

Although acromegaly does very occasionally run in families, most adenomas are not inherited – they usually develop spontaneously as a result of a genetic change within a cell of the pituitary gland. This genetic change switches on a signal that tells cells in the pituitary gland to divide and secrete growth hormone.

The tumour almost never spreads to other parts of the body, but it may grow to more than 1cm in size and compress the surrounding nerves and normal pituitary tissue, which can affect the production of other hormones, such as thyroid hormones released from the thyroid gland.

Who is affected

It’s not clear exactly how many people are affected by acromegaly, although it’s been estimated that around 4 to 13 in every 100,000 people may have the condition.

This means there is likely to be between 2,500 and 8,300 people in the UK with the condition.

Acromegaly can affect people of any age, but it is rare in children. The average age at which people are diagnosed is around 40-45.

Problems caused by acromegaly

Acromegaly can cause a wide range of symptoms that tend to develop slowly over time.

Typical symptoms include:

- joint pain

- large hands and feet

- carpal tunnel syndrome (compression of the nerve in the wrist, causing numbness and weakness of the hands)

- thick, coarse, oily skin

- skin tags

- enlarged lips, tongue and nose

- a protruding jaw and brow

- widely spaced teeth

- deepening of the voice due to enlarged sinuses and vocal cords

- obstructive sleep apnoea (breaks in breathing during sleep due to obstruction of the airway)

- excessive sweating

- fatigue and weakness

- headaches

- impaired vision

- loss of sex drive

- in women, abnormal periods

- in men, erectile dysfunction

- in children and teenagers, excessive height (gigantism)

Some of the above symptoms are the result of the tumour compressing nearby tissues – for example, headaches and vision problems may occur if the tumour squashes nearby nerves.

If you think you have acromegaly, see your GP straight away. Acromegaly can usually be successfully treated with brain surgery and medication, but early diagnosis and treatment is important to prevent the symptoms getting worse and to reduce your chance of getting complications.

Possible complications

If acromegaly is left untreated, you may be at risk of the following health problems:

- type 2 diabetes

- high blood pressure (hypertension)

- cardiovascular disease

- cardiomyopathy (a disease of the heart muscle)

- arthritis as a result of overgrowth of bone and cartilage

- bowel polyps, which can potentially turn into bowel cancer if left untreated

Left untreated, these complications can become serious and fatal.

Diagnosing acromegaly

Blood tests

If your doctor suspects acromegaly from your symptoms, they will order blood tests to measure your levels of human growth hormone.

Levels of growth hormone naturally vary from minute to minute as it is released from the pituitary gland in spurts. Therefore to accurately diagnose acromegaly, growth hormone needs to be measured under conditions that normally suppress growth hormone secretion.

To ensure an accurate result, you may be referred to a hospital doctor for a glucose tolerance test. This involves testing your blood after drinking a solution or drink containing the sugar glucose.

In most people, drinking the glucose solution will suppress the release of growth hormone, but in people with acromegaly, the level of growth hormone in the blood will remain elevated.

Your doctor will also measure your level of IGF-1, which should increase with the level of growth hormone. An elevated IGF-1 level almost always indicates acromegaly.

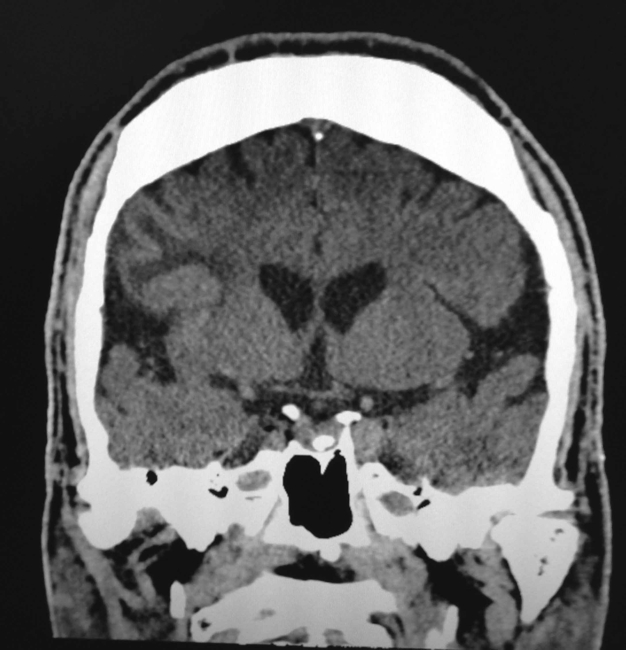

Brain scans

You may then have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of your brain to locate and define the size of the pituitary gland tumour causing your acromegaly. A computerised tomography (CT) scan can be carried out if you are unable to have an MRI scan.

Treating acromegaly

Treatment aims to:

- reduce excess growth hormone to normal levels

- relieve the pressure the tumour is exerting on the surrounding structures

- treat any hormone deficiencies

- improve the symptoms of acromegaly

This is usually achieved through surgical removal of the tumour and medication.

Brain surgery

In most cases, surgery is recommended to remove the adenoma from your pituitary gland. This is effective in most people, although sometimes the tumour is too large to be removed completely.

Under a general anaesthetic, the surgeon will make an incision inside your nose or behind your upper lip to access the gland. An endoscope (a long, thin, flexible tube that has a light source and a video camera at one end) and surgical instruments are then passed through the incisions to remove the tumour.

Removing the tumour promptly relieves the pressure on the surrounding structures and leads to a rapid lowering of growth hormone levels. Facial appearance and swelling often improve within a few days.

Possible complications of surgery include damage to the healthy parts of the pituitary gland, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (which surrounds and protects the brain), and meningitis, though this is rare. Your surgeon will discuss these risks with you and answer any questions you have.

Radiotherapy

If surgery is not possible, or surgery and medication do not cure the condition, radiotherapy aimed at the adenoma may be an option.

This can eventually lead to a reduction in growth hormone levels, although it may not have a noticeable effect for several years and you may need to take medication in the meantime.

There are two main types of radiotherapy for acromegaly:

- Stereotactic radiosurgery – where a high-dose beam of radiation is precisely aimed at the tumour, requiring you to wear a rigid head frame to keep your head still. This can sometimes be done in a single session.

- Conventional radiotherapy – where the tumour is targeted with external beams. This can potentially damage the surrounding pituitary gland and brain tissue, so small doses of radiation are given over four to six weeks, giving normal tissue time to heal in between treatments.

Stereotactic radiosurgery is generally preferred to conventional radiotherapy because it minimises the risk of damage to nearby healthy tissue, although it is not always widely available.

Radiotherapy can have a number of side effects. For example, the treatment will often cause a gradual decline in the production of other hormones from your pituitary gland, so you’ll usually need to take hormone replacement therapy for the rest of your life. There’s also a risk it will impair fertility. Speak to your doctor about the risks involved.

Bowel cancer screening

There is some evidence acromegaly may increase your risk of bowel cancer, so guidelines recommend having a colonoscopy when you are diagnosed with the condition, and regular colonoscopy screening from the age of 40.

A colonoscopy is an examination of your entire large bowel using a type of endoscope called a colonoscope that is inserted into your bottom. See bowel cancer tests for more information about what a colonoscopy involves.

Outlook

Treatment is often effective at stopping the excessive production of growth hormone and improving problems caused by the condition. Treatment can also increase life expectancy to around that of someone without acromegaly.

Some treatments can take a long time to have a noticeable effect and you may need to take medication for a long period of time.

After treatment, you’ll need regular follow-up appointments with your specialist for the rest of your life. These will be used to monitor your pituitary function, check you are on the correct hormone replacement treatment, and to ensure the condition does not return.

Without treatment, acromegaly can cause long-term problems and may reduce life expectancy by a number of years.