Introduction

Synaesthesia is a condition where a sensation in one of the senses, such as hearing, triggers a sensation in another, such as taste.

For example, some people with synaesthesia can taste numbers or hear colours.

A wide range of different synaesthetic experiences have been reported and recorded – a typical example is someone who described experiencing the colour red every time he heard the word “Monday”.

What are the different types of synaesthesia?

There are many different types of synaesthesia, and many people with synaesthesia will experience more than one of these – for example, taste, sound and touch may all produce colours.

Colours and patterns

Research suggests that the most common synaesthetic experiences are associating days, months, numbers and the alphabet with:

patterns or shapes (for example, envisaging the months laid out in lines, spirals or circles)

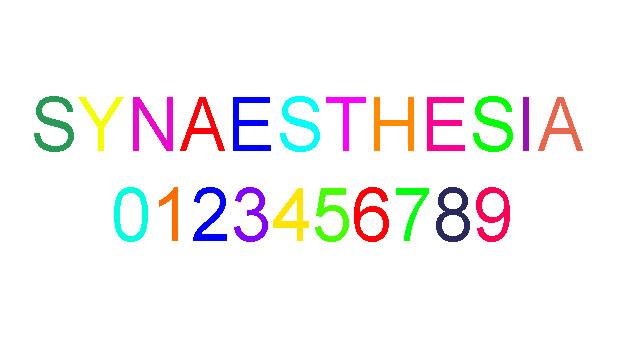

distinctive colours – for example, “A” may be red and “B” may be blue

Synaesthesia affects people differently. Two people with synaesthesia will often disagree over the colour of letters.

However, there are some trends that appear common to all people with the condition – A is generally perceived as red, B is often blue, and C is often yellow.

Taste and smell

For some people with synaesthesia, spoken words trigger a particular taste, as well as a particular texture, place in the mouth and temperature (for example, “runny egg yolk”).

Taste can also produce colour sensations, or shapes that can be “felt”.

Certain odours may also be perceived as shapes and/or colours, but this form of synaesthesia is thought to be rare.

Touch and other body sensations

Some people experience touch just by looking at someone being touched. This is known as “mirror touch” synaesthesia.

Feelings of pain or touch can also trigger visions or colour, and there has been a documented case of words triggering feelings of body movement.

Advice for people with synaesthesia

Most people with synaesthesia have had it since childhood, so it feels perfectly normal to experience the world in this way. It’s not obtrusive and does not affect day-to-day life. It’s not necessary to see a doctor.

If you think your child has synaesthesia

If you are a parent of a child with synaesthesia, you may wish to discuss it with their teacher so they are aware of it. There is evidence that synaesthesia affects educational ability, either by slightly distracting the pupil, or (most often) by giving slight learning advantages.

It may also be true that your child will learn in different ways to other children. For instance, many people with synaesthesia report a visual style of thinking.

If it comes on suddenly in adulthood

If you suddenly begin to experience symptoms of synaesthesia for the first time as an adult, it’s a good idea to see your GP for an assessment.

This is because there could be underlying factors related to your brain and nervous system that may need investigating.

Is synaesthesia linked to other conditions?

Because the number of people with synaesthesia is relatively small, it is not yet possible to know this conclusively.

An Australian study did not find any evidence of an association between synaesthesia and various mental health problems. In fact, there is growing evidence that synaesthesia may be linked to certain advantages, including enhanced memory, superior perception and being able to think more quickly.

Two small studies published in 2013 suggest that synaesthesia is more common in adults with autism (also known as autistic spectrum disorder) than in adults who do not have an autistic spectrum disorder.

The studies involved screening people with and without autism for synaesthesia. In adults with autism, the prevalence of synaesthesia was estimated to be 17-19%, whereas adults without autism have a much lower prevalence of 2% (for more information, read NHS News: Synaesthesia may be ‘more common’ in autism).

These results appear broadly reliable, but they need to be confirmed in larger studies. If true, these findings imply that the two conditions may share some common cause in the brain.

However, it’s important to note that most people with autism do not have synaesthesia, and that most people with synaesthesia do not have autism.

What’s the cause?

It’s likely that the brain of someone with synaesthesia is “wired” differently, or has extra connections.

A brain imaging study has shown that when some people with synaesthesia hear spoken words, a part of their brain normally used to process colour from vision lights up.

Synaesthesia runs in families, although it may skip a generation and may not affect immediate relatives. It’s possible for only one twin to have the condition, or for family members to show different types of synaesthesia. In summary, there is a genetic contribution to synaesthesia, but the environment is also important.

It’s possible for people to “grow out of” synaesthesia: there have been cases of people claiming that they used to experience synaesthesia, but no longer do.

How do people with synaesthesia feel about their condition?

Interviews with people who have synaesthesia show a wide range of feelings towards their condition.

Many are positive about it (“I feel sorry for people who don’t have this”), and can’t imagine their life without it.

Some feel neutral about it, and treat it as something they’ve become used to, which doesn’t affect them in any way.

For a minority, the sensations can disrupt their chain of thought and be intrusive.

How common is it?

Synaesthesia has been estimated to affect at least 4% of the UK population.

Researchers at the University of Sussex have estimated that 1-2% of the UK population experience colour when they see, hear or think about letters and numbers, and that synaesthesia is just as common in women as in men (read the study).