Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a rare and serious condition that causes painful blisters to develop on the skin and lining of the mouth, nose, throat and genitals.

The blisters are fragile and can easily burst open, leaving areas of raw unhealed skin that are very painful and can put you at risk of infections.

There’s currently no cure for pemphigus vulgaris, but treatment can help keep the symptoms under control.

The condition can affect people of all ages, including children, but most cases develop in older adults between the ages of 50 and 60. It isn’t contagious and can’t be passed from one person to another.

Symptoms of pemphigus vulgaris

The blisters usually develop in the mouth first, before affecting the skin a few weeks or months later.

There tends to be times when the blisters are severe (flare-ups), followed by periods when they heal and fade (remission). It’s impossible to predict when this might happen and how severe the flare-ups will be.

Blisters in the mouth often turn into painful sores, which can make eating, drinking and brushing teeth very difficult. The voice can become hoarse if they spread to the voice box (larynx).

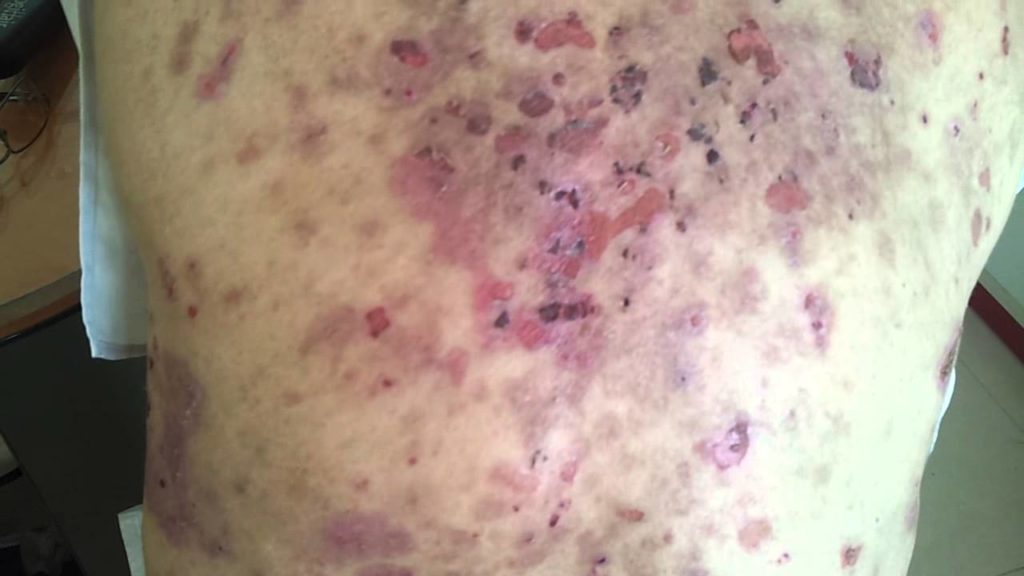

Sores on the skin can join together to form large areas of painful, raw-looking skin, before crusting over and forming scabs. They don’t usually leave any scars, although affected skin can occasionally become permanently discoloured.

When to seek medical advice

See your GP if you have severe or persistent blisters or sores in your mouth or on your skin.

It’s unlikely that you have pemphigus vulgaris, but it’s a good idea to get your symptoms checked out.

If your GP thinks your symptoms could be caused by a serious condition such as pemphigus vulgaris, they can refer you to a dermatologist (skin specialist) for some tests.

The dermatologist will examine your skin and mouth, and may remove a small sample (biopsy) from the affected area so it can be analysed in a laboratory. This can confirm whether you have pemphigus vulgaris.

What causes pemphigus vulgaris?

Pemphigus vulgaris is what’s known as an autoimmune condition. This means that something goes wrong with the immune system (the body’s defence against infection) and it starts attacking healthy tissue.

In cases of pemphigus vulgaris, the immune system attacks cells found in a deep layer of skin, as well as cells found in the mucous membrane (the protective lining of the mouth, nostrils, throat, genitals and anus). This causes blisters to form in the affected tissue.

It is unclear what causes the immune system to go wrong in this way. Certain genes have been linked to an increased risk of pemphigus vulgaris, although it doesn’t tend to run in families.

Treatments for pemphigus vulgaris

The symptoms of pemphigus vulgaris can often be controlled with a combination of medicines that help stop the immune system attacking the body.

Most people will start off taking high doses of steroid medication (corticosteroids) for a few weeks or months. This helps stop new blisters forming and allows existing ones to heal.

To reduce the risk of side effects from steroid medication, the dose is then gradually reduced and another medication that reduces the activity of the immune system is taken alongside it.

It may eventually be possible to stop taking medications for pemphigus vulgaris if the symptoms don’t come back, although many people need ongoing treatment to prevent flare-ups.

Read more about treating pemphigus vulgaris.

Risk of infected blisters

There is a high risk of blisters caused by pemphigus vulgaris becoming infected, so it’s important to look out for signs of infection.

Signs of an infected blister can include:

the skin becoming painful and hot

yellow or green pus in the blisters

red streaks leading away from the blisters

Don’t ignore these signs, as an infected blister could potentially lead to a very serious infection if left untreated. Contact your GP or dermatologist for advice straight away.