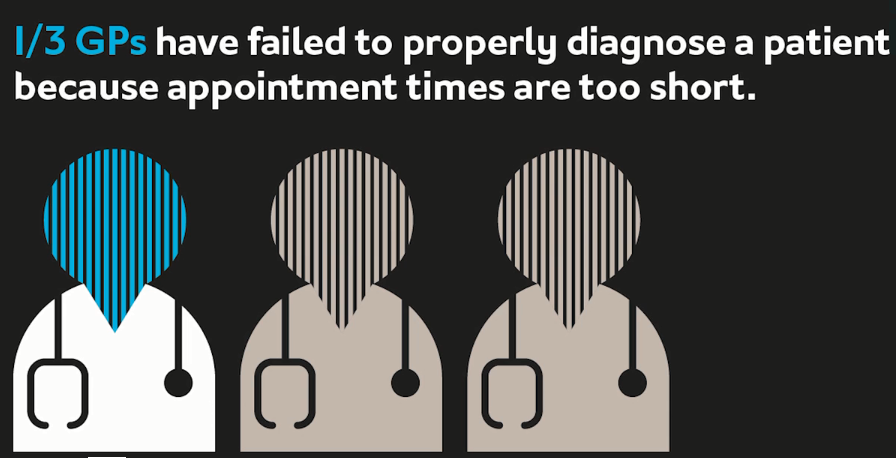

ONE in three GP’s admit they have failed to properly diagnose patients because short appointment times have meant symptoms have been missed, according to new research.

Misdiagnoses meant sick patients are forced to return for repeat appointments and further medical treatment as tight consultation windows did not provide enough time for doctors to assess them properly.

A staggering 94 per cent of NHS doctors surveyed said short appointment times put patients at risk, with GP’s reporting that they felt the minimum ‘safe’ timeframe would be 16 to 20 minutes.

Four in five said they don’t always have time to properly diagnose patients, with 55 percent fearing they have missed serious health issues are missed and 37 per cent believing they have prescribed the wrong course of treatment.

Half of the GP’s surveyed said they are expected to keep appointment times to less than ten minutes. Others were pressured to reduce this further depending on patient demand for attention.

Nearly all GP’s (94.5 per cent) said they felt stressed or anxious about appointment times. When asked what changes would improve their working conditions the most common answer was for them to be given more time to diagnose patients. This was more of a priority to GP’s than better resources, flexible working or better pay.

One GP, said: “I often don’t have enough time to spend with one patient to make a proper diagnosis. Recently it took three weeks and repeat appointments to get to the bottom of a patient’s medical condition and offer the correct solution. It made me feel terrible as she really needed help, but I didn’t have enough time for her to be completely open about her situation. Had we had more time in the first appointment it would have allowed me to get to the bottom of her complaint straight away.”

Another said: “If I’d had more time during my first appointment with one patient recently I believe I would have been able to ask her more questions and uncover the issue. Instead she had to come for a second appointment and required tests. We need more time.”

The research, conducted by Slater and Gordon, quizzed 200 GPs about the pressures they were under.

Parm Sahota from Slater and Gordon said: “Working in this area of law I already knew GPs were stretched, but the timeframes they are expected to practice within are suffocating.

“We trust our family doctors to listen to our concerns and identify any issues, without worrying about rushing us through to meet unsafe deadlines which are not best practice. They need to have enough time to do their jobs correctly and robustly for the health of the UK.”

Another outcome was the effect on patients’ experience, with many GPs fearing patients felt unheard or unvalued (51 per cent) and were losing confidence in GP practices (51 per cent).

Parm Sahota from Slater and Gordon said: “This research shows a lack of time directly effects the level of care GPs can provide to patients. But it’s not just the patients who lose out, it’s also effecting the mental health of our GPs.

“We all deserve to work in a safe and supportive workplace, this should be even more important for those we entrust with our health. We also want public healthcare to be functioning as best it can, which means making the NHS an attractive, safe and enjoyable place to work.”

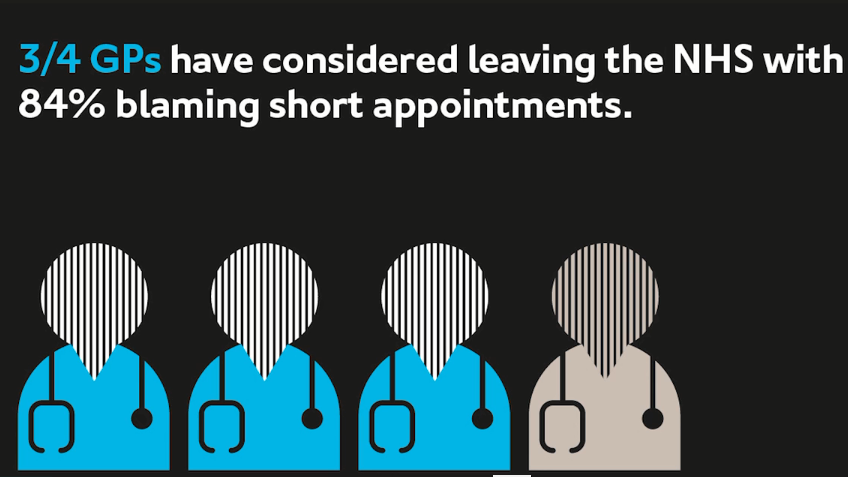

Of those polled, nearly three quarters of NHS GPs considered leaving the service for private practice and 45 per cent have considered leaving medicine all together. Over 84 per cent said short appointments were a factor or the main reason they were considering leaving the public system.

Ultimately 43 per cent said if they knew about the pressure on GPs before they began studying, they would have chosen a different career.

The GPs polled ranged in length of service from two years to more than 30 years, with the majority serving between five and 15 years.

Case study – Dr Eleanor Holmes, 39

Dr Holmes qualified as a GP in 2008. She worked for 10 years in Newcastle and Northumberland: “I’m now on a sabbatical because working as a GP within the NHS had become so bad for my health. Over the last 10 years I’ve changed workplaces, working patterns, taught at university, while keeping up hobbies and exercise. This is not a profession you give up lightly, but no matter what changes I made I couldn’t make it healthy or safe to continue working. I found myself in a position where I could not care for myself, and if I couldn’t care for myself how could I care for anyone else? “I know so many people who have put every other aspect of their life on hold to be GPs. They prioritise patients and the care they deliver above their own wellbeing. This is not sustainable. I want to be a doctor who is fully there for my patients, giving the quality of care I know I am capable of. I believe the current system does not allow for this.

“A ‘typical’ workload is 30 patients each day, over 10 to 12 hours. Normally this would look like 14 patients in the morning, followed by two home visits, then 14 patients in the afternoon. Appointments are generally 10 minutes long but can vary between practices. If you’re ‘on‐call’ and triaging patients on the phone you could speak to double that in a morning. When I was ‘on call’ I could have contact with 50 or 60 patients, or more, a day. This is not safe working.

“Each 10‐minute appointment creates work too, like referrals, tests to order, results to check, reports to write and paperwork to chase. We also have to write legally binding medical records, able to stand up in court, all in 10 minutes. We have administration time built into our contracts, but this doesn’t begin to cover the work generated.

“Not only are timeframes and patient volumes impossible, patients’ needs have changed. It is normal for allied health professionals, like nurse practitioners, to take more straight‐forward cases. Leaving GPs to see patients with increasingly complex needs which cannot be safely managed in 10 minutes.

“For most GPs it’s like you’re on a treadmill, you’re treated like expendable machines under unrelenting pressure. Most GPs want to do their very best for their patients, but the system will not let them. Often doctors burnout, suffer significant mental health problems, or leave the profession. If they stay, GPs have to reduce their clinical loads significantly, or diversify their roles to avoid becoming disconnected and cynical.”