Symptoms of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) can vary in severity, ranging from mild to life-threatening.

Although specific symptoms depend on the type of EB, there are some common features, including:

skin that blisters easily

blisters inside the mouth

blisters on the hands and soles of the feet

scarred skin, sometimes with small white spots called milia

thickened skin and nails

Symptoms of epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS)

The symptoms of the most common variants of epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) are described below.

EBS (localised)

Localised EBS is the most common form of EBS. It’s characterised by painful blisters on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet that develop after mild or moderate physical activity, such as walking, gardening or playing sport.

Although the blisters often form on the hands and feet, it’s not uncommon for them to develop on other parts of the body as well, such as the buttocks or inner thighs, after they’ve been subjected to friction during activities such as riding a bike.

Excessive sweating can make the blisters worse, so localised EBS is often more noticeable during the summer. The blisters usually heal without scarring.

Symptoms usually become apparent during early childhood, although mild cases may go undiagnosed until early adolescence.

Some adults with localised EBS may experience thickening of the skin on their palms and the soles of their feet, as well as their fingernails and toenails.

EBS (generalised intermediate)

In this form of EBS, blisters can form anywhere on the body in response to friction or trauma. The symptoms are also usually more troublesome during hot weather.

There may be mild blistering of the mucus membranes, such as the inside of the nose, mouth and throat.

Scarring and milia (small white spots) may occur on the skin, but this is uncommon.

The symptoms usually begin during birth or infancy. As with localised EBS, adults may experience thickening of the skin on their palms and the soles of their feet, as well as their fingernails and toenails.

EBS (generalised severe)

This form of EBS is the most severe type, where children experience widespread blistering. In the most severe cases, a child can develop up to 200 blisters in a single day.

The widespread blistering can make the skin vulnerable to infection and affect an infant’s normal feeding pattern, which means they may not develop at the expected rate.

Painful blisters on the soles of the feet can affect an infant’s ability to walk and may mean they start to walk later.

Blisters can also develop inside the mouth and throat, making eating – and sometimes speaking – difficult and painful. Thickening or loss of the fingernails and toenails is another common symptom.

The symptoms usually develop at birth, but the blistering gradually improves through childhood and adolescence – so adults may only experience occasional blistering.

However, it’s common for the skin of the palms and soles to become progressively thicker with age, and this may make walking or activities using the hands difficult or painful.

Symptoms of junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB)

There are two main variants of junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB), discussed below.

JEB localised (non-Herlitz)

Non-Herlitz JEB causes widespread blistering of the skin and mucus membranes. Blistering of the scalp is common and may lead to scarring and permanent hair loss.

Other common symptoms include:

long-term injuries to the skin and underlying tissue, especially of the lower legs

scarring of the skin

deformity or loss of fingernails and toenails

pigmented (coloured) areas of skin that look like large, irregular moles

Tooth enamel isn’t properly formed, which means teeth may be discoloured, fragile and prone to tooth decay. The mouth is also frequently affected by blisters and ulcers, which may make eating difficult.

Some patients also develop problems with the urinary tract, such as blistering or scarring of the urethra (tube urine passes through from the bladder).

The symptoms usually develop at birth or shortly afterwards and can improve with age.

As adults, people with this form of EB have an increased risk of developing skin cancer, so regular review by a dermatologist (skin specialist) familiar with EB is recommended.

JEB generalised (Herlitz)

This is the most severe type of JEB, although it’s incredibly rare.

Herlitz JEB causes widespread blistering of both the skin and the mucus membranes. In particular, the following areas of the body are affected by blistering and chronic ulcers:

the genitals and buttocks

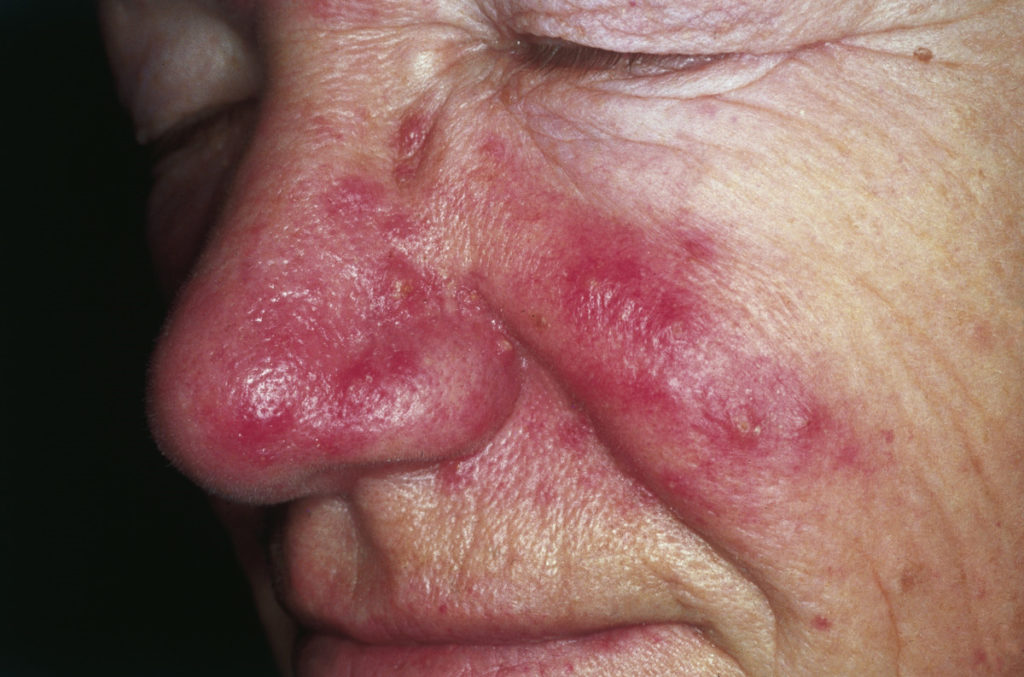

around the nose and mouth

the fingertips

the toes

the neck

inside the mouth and throat

the eyes

Complications of Herlitz JEB are common and include:

anaemia

tooth enamel defects and decay

malnutrition and delayed growth

breathing difficulties

Because of these complications, the outlook for children with Herlitz JEB is very poor. Around 40% of children with the condition won’t survive the first year of life, and most won’t survive more than five years.

Sepsis and respiratory failure (due to blistering and narrowing of the airways) are the most common causes of death.

Symptoms of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB)

The three most common variants of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) are discussed below.

Dystrophic EB (dominant)

Dominant DEB causes blistering at places on the body that experience trauma, often the hands, feet, arms and legs, which usually results in scarring. Milia (tiny white spots) often form at the site of the blisters.

The nails will usually become thickened and abnormally shaped, or even lost altogether. The mouth is often affected, which can make eating or cleaning teeth painful.

Some people with dominant DEB have mild symptoms with very few blisters, and the only sign of the disease may be misshapen or missing nails.

The symptoms of dominant DEB usually develop at birth or shortly afterwards, but may not occur until later in childhood.

Dystrophic EB (recessive, severe generalised)

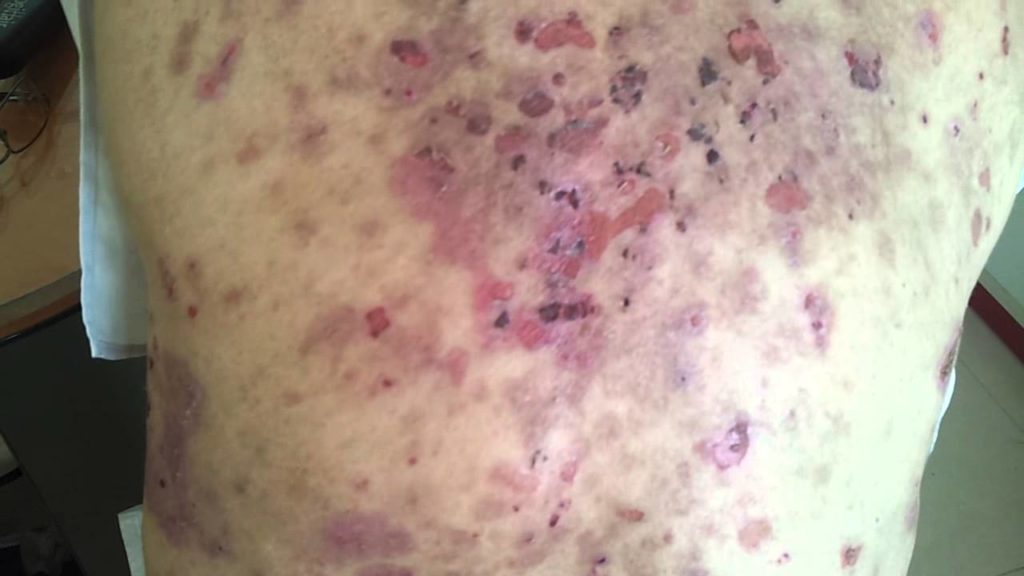

Severe generalised recessive DEB is the most severe type of DEB. It causes severe and widespread skin blistering that often leaves areas covered with persistent ulcers.

Repeated scarring to hands and feet can result in the loss of nails. Spaces between fingers and toes can fill with scar tissue so hands and feet take on a mitten-like appearance.

Extensive blistering can also occur on the mucus membranes, particularly inside the:

mouth

oesophagus (tube connecting the mouth and stomach)

anus

Tooth decay and repeated scarring in and around the mouth are both common. This can often cause problems with speaking, chewing and swallowing. Repeated blisters on the scalp may also reduce hair growth.

As a result, many children with this form of DEB will experience anaemia, malnutrition and delayed or reduced growth. The eyes can also be affected by blistering and scarring, which is painful and can lead to vision problems.

The symptoms of severe generalised recessive DEB are usually present at birth. There may be areas of missing skin at birth, or blistering developing very shortly afterwards.

People with this type of DEB have a high risk of developing skin cancer at the site of repeated scarring. It is estimated that more than half of people with severe generalised recessive DEB will develop skin cancer by the time they are 35.

Therefore, awareness of this problem and frequent check-ups (possibly twice a year) with a dermatologist are recommended.