Don’t let a positive Rheumatoid Factor test confuse you. Rheumatoid Arthritis is only one reason why you may test positive, here are 5 more.

Don’t let a positive Rheumatoid Factor test confuse you. Rheumatoid Arthritis is only one reason why you may test positive, here are 5 more.

Rheumatoid Arthritis affects almost 1% of people in the US and is a common concern as we get older and start to have joint pain. Learn the facts so you can talk more with your doctor.

Crowdsourcing has become an increasingly popular way to develop machine learning algorithms to address many clinical problems in a variety of illnesses. Today at the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) annual meeting, a multicenter team led by an investigator from Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) presented the results from the RA2-DREAM Challenge, a crowdsourced effort focused on developing better methods to quantify joint damage in people with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

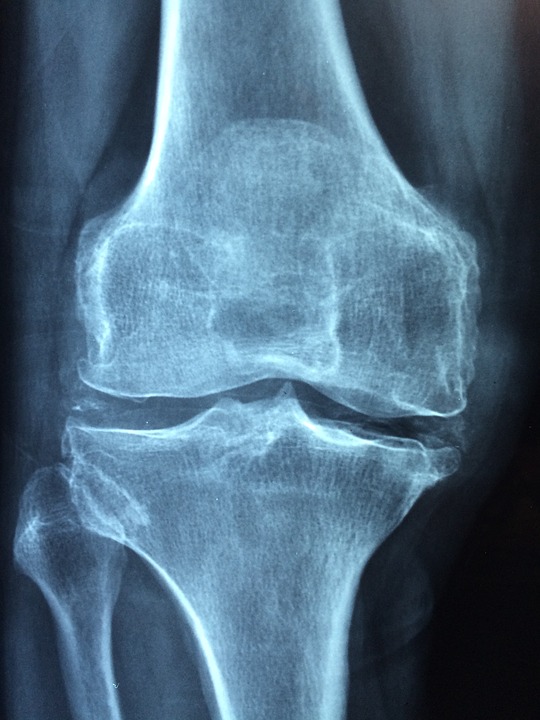

Damage in the joints of people with RA is currently measured by visual inspection and detailed scoring on radiographic images of small joints in the hands, wrists and feet. This includes both joint space narrowing (which indicates cartilage loss) and bone erosions (which indicates damage from invasion of the inflamed joint lining). The scoring system requires specially trained experts and is time-consuming and expensive. Finding an automated way to measure joint damage is important for both clinical research and for care of patients, according to the study’s senior author, S. Louis Bridges, Jr., MD, PhD, physician-in-chief and chair of the Department of Medicine at HSS.

“If a machine-learning approach could provide a quick, accurate quantitative score estimating the degree of joint damage in hands and feet, it would greatly help clinical research,” he said. “For example, researchers could analyze data from electronic health records and from genetic and other research assays to find biomarkers associated with progressive damage. Having to score all the images by visual inspection ourselves would be tedious, and outsourcing it is cost prohibitive.”

“This approach could also aid rheumatologists by quickly assessing whether there is progression of damage over time, which would prompt a change in treatment to prevent further damage,” he added. “This is really important in geographic areas where expert musculoskeletal radiologists are not available.”

For the challenge, Dr. Bridges and his collaborators partnered with Sage Bionetworks, a nonprofit organization that helps investigators create DREAM (Dialogue on Reverse Engineering Assessment and Methods) Challenges. These competitions are focused on the development of innovative artificial intelligence-based tools in the life sciences. The investigators sent out a call for submissions, with grant money providing prizes for the winning teams. Competitors were from a variety of fields, including computer scientists, computational biologists and physician-scientists; none were radiologists with expertise or training in reading radiographic images.

For the first part of the challenge, one set of images was provided to the teams, along with known scores that had been visually generated. These were used to train the algorithms. Additional sets of images were then provided so the competitors could test and refine the tools they had developed. In the final round, a third set of images was given without scores, and competitors estimated the amount of joint space narrowing and erosions. Submissions were judged according to which most closely replicated the gold-standard visually generated scores. There were 26 teams that submitted algorithms and 16 final submissions. In total, competitors were given 674 sets of images from 562 different RA patients, all of whom had participated in prior National Institutes of Health-funded research studies led by Dr. Bridges. In the end, four teams were named top performers.

For the DREAM Challenge organizers, it was important that any scoring system developed through the project be freely available rather than proprietary, so that it could be used by investigators and clinicians at no cost. “Part of the appeal of this collaboration was that everything is in the public domain,” Dr. Bridges said.

Dr. Bridges explained that additional research and development of computational methods are needed before the tools can be broadly used, but the current research demonstrates that this type of approach is feasible. “We still need to refine the algorithms, but we’re much closer to our goal than we were before the Challenge,” he concluded.

When joints flare up in people with rheumatoid arthritis and related diseases, the joints involved are often the same as those affected before. For example, if arthritis started in the right knee, it is much more likely to flare there than in the left knee, even if the arthritis had been in remission for years. As a result, each patient develops a highly individual disease pattern. But why this happens has remained a mystery.

“Overwhelmingly, flares occur in a previously involved joint,” says Peter Nigrovic, MD, chief of the division of immunology at Boston Children’s Hospital. “Something in that joint seems to remember, ‘this is the joint that flared before.’”

A new study, co-led by Nigrovic with colleagues at Boston Children’s and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, shows where that memory is housed: in a type of immune cell called a tissue-resident memory T cell. Specifically, these T cells reside in the synovium, the tissue that lines the inside of the capsule surrounding the joint. Findings were published October 26 in Cell Reports.

“We showed that these T cells anchor themselves in the joints and stick around indefinitely after the flare is over, waiting for another trigger,” says Nigrovic. “If you delete these cells, arthritis flares stop.”

The team demonstrated this phenomenon in three separate mouse models of inflammatory arthritis. Two models used chemical triggers to cause joint inflammation, and the third used a genetic trigger (loss of a protein that blocks the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1). Once activated, resident memory T cells in the joints rallied other immune cells, leading to an arthritis flares limited to specific joints. Elimination of these T cells blocked additional flares from occurring.

“Right now, treatment of rheumatoid arthritis has to continue lifelong; although we can successfully suppress disease activity in many patients, there is no cure,” says Nigrovic. “We think our findings may open up new therapeutic avenues.”

Nigrovic also believes the findings apply to other types of autoimmune arthritis, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Margaret Chang, MD, PhD, an attending rheumatologist at Boston Children’s and co-first author on the paper, is leading an effort to find practical ways of targeting tissue-resident memory T cells in humans.

Nigrovic and colleagues took their cue from dermatology. Tissue-resident memory T cells were originally found in skin, where a “memory” pattern is well known to dermatologists. In psoriasis, for example, patients get plaques in same places over and over. The same is often true in cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions, such as reactions to nickel from jewelry or wristwatches. “A person reacting to nickel through a belt buckle may also develop a rash on their wrist, where they wore a nickel-containing watch as a child,” says Nigrovic.

Anaïs Levescot, PhD, a previous postdoctoral fellow in the Nigrovic lab, is co-first author on the paper with Chang. Nigrovic and Robert Fuhlbrigge, MD, PhdD of Children’s Hospital of Colorado (formerly Boston Children’s) conceptualized the T resident memory cell hypothesis together and are co-corresponding authors.

The work was enabled by a philanthropic gift from Jacqueline and Stuart Arbuckle. Other funders were the Rheumatology Research Foundation, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, the American Academy of Neurology, the Arthritis National Research Foundation, and the Fundación Bechara.

Blanca is 60 and has struggled with severe rheumatoid arthritis for 15 years. She had seen conventional doctors and tried many other things prior to joining the program. She spent $15,000 on stem cell therapy and countless supplements and acupuncturist along with taking 3 medications from her rheumatologist. The problem is, she got worse. Her pain got so bad it was 9/10 to the point she couldn’t walk, drive, even change her own clothes. She had to depend on others for basic self-care and had to retire early. Her fatigue was 10/10 and she was bedridden, depressed, and ready to give up. Find out how she was able to turn this around in just a few months.