A ground-breaking study – the largest of its kind globally – has found children with multiple sclerosis (MS) have better outcomes if treated early and with the same high-efficacy therapies as adults.

There are a limited number of therapies approved for children with MS, with only one considered to be of high efficacy – meaning highly effective.

However, a Royal Melbourne Hospital (RMH) observational study has determined that paediatric patients should be treated with the same high-efficacy treatments offered to adults as early in their diagnosis as possible to avoid the onset of significant disability.

“We found that patients who were treated with high-efficacy disease-modifying therapies during the initial phases of their disease benefitted the most compared to patients who were not treated,” Dr Sifat Sharmin, a Research Fellow at the Royal Melbourne Hospital’s Neuroimmunology Centre, and the University of Melbourne’s Department of Medicine, said.

“Based on our findings we recommend that patients with paediatric-onset multiple sclerosis should be treated early in the disease course, when the disability is still minimal, to preserve neurological capacity before it’s damaged.”

The observational study analysed global data on more than 5,000 people diagnosed with MS during childhood over the last 30 years, including from MSBase, a large international registry encompassing 41 countries, and a national registry in Italy, where the disease is highly prevalent.

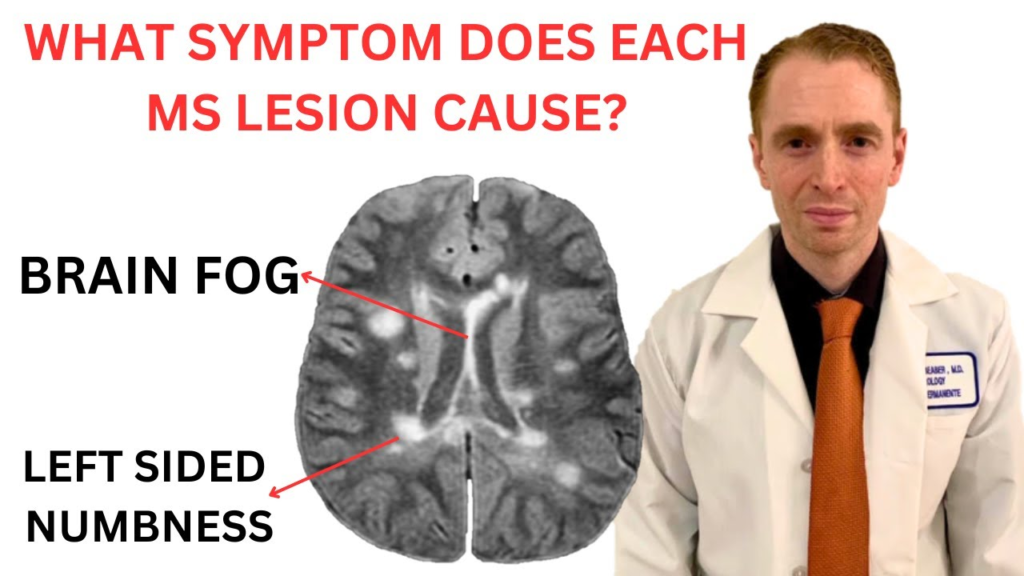

It compared the strength of treatment with the severity of the disease later in life, and concluded patients treated with the most effective treatments early on in their diagnosis were less likely to experience disability worsening. These disease-modifying therapies include highly effective antibodies that change the way in which an individual’s immune system behaves.

The findings were published in the prestigious journal the Lancet Child and Adolescent Health this week.

The research also confirmed that any treatment – including low-efficacy treatments – was better than no treatment

Dr Sharmin, who led the study, said because paediatric-onset MS was a rare disease – about four to eight per cent of MS patients are diagnosed before age 18 – it wasn’t as well investigated.

“This is the largest study of its kind for paediatric MS,” she said.

“We hope this may have some policy implications so children with MS can access the most effective therapies as early as possible.”

MS is a chronic condition that occurs when the immune system attacks the brain and spinal cord. There is currently no cure for the condition.