The role that Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) plays in the development of multiple sclerosis (MS) may be caused a higher level of cross-reactivity, where the body’s immune system binds to the wrong target, than previously thought.

In a new study published in PLOS Pathogens, researchers looked at blood samples from people with multiple sclerosis, healthy people infected with EBV and people recovering from glandular fever caused by recent EBV infection. The study investigated how the immune system deals with EBV infection as part of worldwide efforts to understand how this common virus can lead to the development of multiple sclerosis, following 20 years of mounting evidence showing a link between the two.

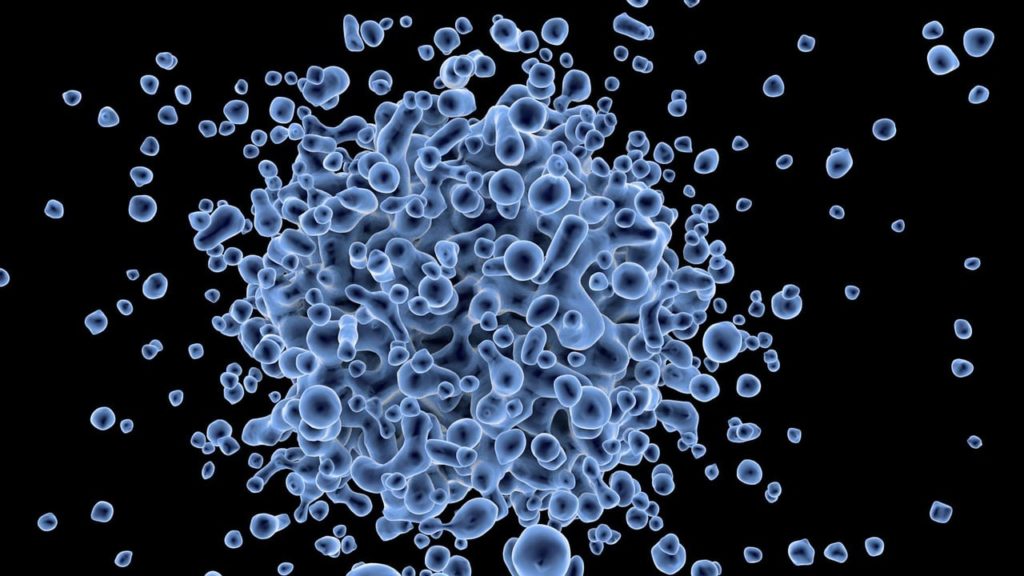

While previous studies have shown that antibody responses to one EBV protein — EBNA1 — also recognise a small number of central nervous system proteins, this study found that T-cells, another important part of the immune system that targets viral proteins, can also recognise brain proteins.

A second important finding was that these cross-reactive T-cells can be found in people with MS and those without the disease. This suggests that differences in how these immune cells function may explain why some people get MS after EBV infection.

Dr Graham Taylor, associate professor at the University of Birmingham and one of the corresponding authors of the study, said:

“The discovery of the link between Epstein-Barr Virus and Multiple Sclerosis has huge implications for our understanding of autoimmune disease, but we are still beginning to reveal the mechanisms involved. Our latest study shows that following Epstein-Barr virus infection, there is a great deal more immune system misdirection, or cross-reactivity than previously thought.”

“Our study has two main implications. First, the findings give greater weight to the idea that the link between EBV and multiple sclerosis is not due to uncontrolled virus infection in the body. Second, we have shown that the human immune system cross-recognises a much broader array of EBV and central nervous system proteins than previously thought and that different cross-reactivity patterns exist.

“Knowing this will help identify which proteins are important in MS and may provide targets for future personalised therapies.”

T Cells are involved.

During blood testing, the team also found evidence that cross-reactive T cells targeting Epstein-Barr virus and central nervous system proteins are present in many healthy individuals.

Dr Olivia Thomas from the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and joint corresponding author of the paper said:

“Our detection of cross-reactive T-cells in healthy individuals suggests that these cells’ ability to access the brain is important in MS.

“Although our work shows the relationship between EBV and MS is now more complex than ever, it is important to know how far this cross-reactivity extends to fully understand the link between them.”