Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological conditions worldwide; with around 600,000 people in the UK being diagnosed with epilepsy; 112,000 of these being children and young people.

Purple Day (26th March 2019) exists to promote international awareness, education and conversation about the condition. Epilepsy Action is calling for people to support Purple Day, and start talking about the effects that epilepsy has upon those living with the condition, and their family and friends.

One in every 240 children aged 16 and under in the UK will be diagnosed with epilepsy. Some of these children will be babies, some will be starting school and some will be teenagers. Every year, around 40-80 of these children will die because of their epilepsy.

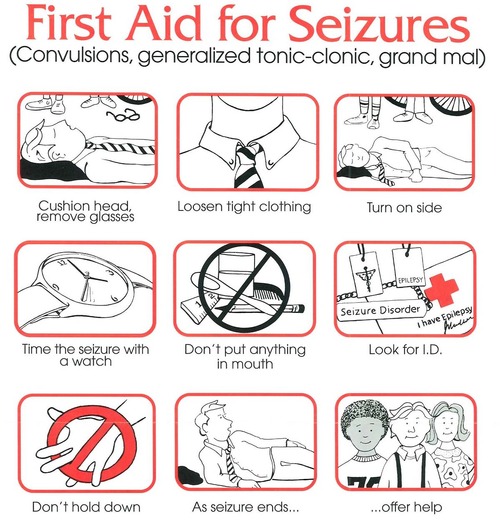

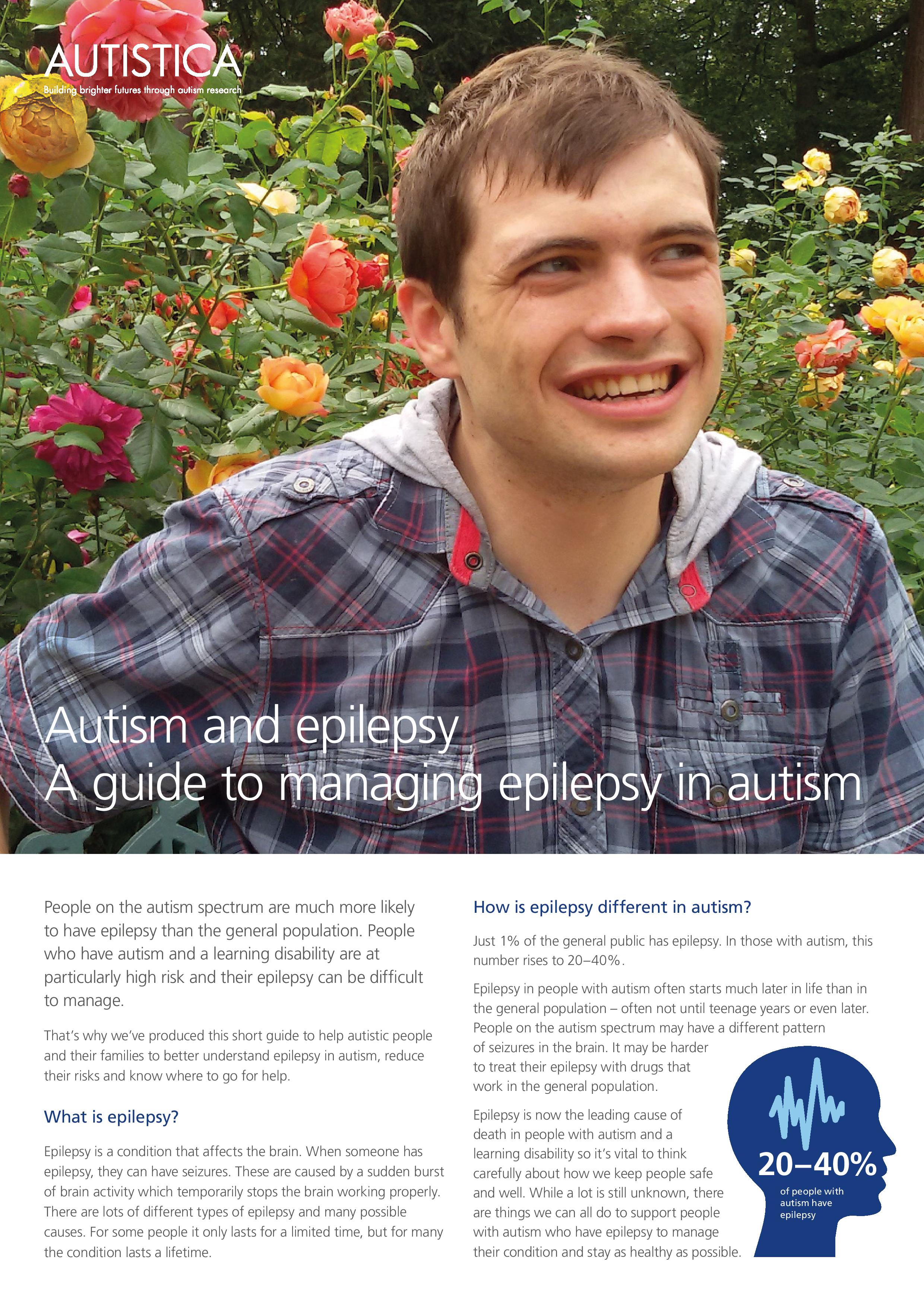

Epilepsy is a condition that affects the brain. A seizure happens when there is a sudden burst of intense electrical activity in the brain. There are many different types of epileptic seizures, and these can affect people differently such as; having strange sensations, movements that can’t be controlled and falling to the floor and shaking.

Children with epilepsy also have a one in 4,500 risk of ‘Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy’ (SUDEP), which is when a child with epilepsy dies suddenly and no reason can be found.

[wp_ad_camp_”]

Epilepsy Action chief executive Philip Lee said:“Finding out you have epilepsy is scary at any age. For young children, it can be terrifying. This Purple Day, Epilepsy Action wants to help children and their families to learn more about epilepsy, let them know they’re not alone and give them the confidence to deal with their diagnosis. We also know that it can be very hard for children to put into words their epilepsy and how it affects them.”

Children with epilepsy are consistently found to be behind their peers academically, and to report a reduced quality of life compared to that of their peers. Supporting Purple Day can help explain epilepsy to children in a way that they understand, and also get more resources to teaching staff meaning children with epilepsy can be better supported to succeed in school.

Epilepsy Action has created a short video with groups of children, some living with epilepsy, talking through what the condition is and how it affects their lives.

<

Rachael King, mum to Jenson, William and Darcie who took part in the filming said:“I think it’s really important for the children to talk about their epilepsy – not only to raise awareness of the condition and what to do if they have a seizure but also so they can share their experiences in a positive way and be proud of how strong they are. I don’t want their epilepsy to ever hold them back through childhood or anything they want to do in life. By sharing their journey from an early age it will hopefully make more people aware of the condition and get support from friends – putting an end to any misconceptions and prejudice about the condition.”

For more information visit https://www.epilepsy.org.uk/