A sizeable percentage of men suffer from prostate cancer, and still there’s basically no support initiatives compared to something like breast cancer. This is an initiative to propagate awareness. Please support this and spread awareness of the lethal disease.

Cancer

A nagging sore throat may be an early sign of cancer

“Sore throat that won’t go away ‘could be a sign of cancer’ doctors warned,” reports The Independent.

Cancer of the larynx, or voice box, affects about 1,700 people a year in the UK. Most cases develop in people aged 60 and above and it is more common in men. It can be treated, and early detection and treatment can make a real difference. Laryngeal cancer is strongly linked to tobacco smoking, secondhand smoke and heavy drinking.

The main symptom of laryngeal cancer is hoarseness. But researchers have now looked at the records of 806 patients with laryngeal cancer and 3,559 without it to see if there are other warning signs GPs should be aware off.

Their analysis suggests that certain combinations of symptoms may require further testing. A potentially serious pattern of symptoms was found to be when hoarseness was combined with a persistent sore throat. Other potential “red flags” included combinations of sore throat with earache, difficulty breathing, difficulty swallowing and insomnia.

Hoarseness, however, remained the most common individual symptom.

The research could be used to update or expand clinical guidelines about when GPs should refer people with suspected cancer for further tests.

If you do have a sore throat, there is no need to panic as it is highly unlikely to be due to cancer and your pharmacist should be able to recommend suitable treatments. But if symptoms do not pass within 1 week then contact your GP for advice.

Where did the story come from?

The researchers who carried out the study were from the University of Exeter. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research and published in the peer-reviewed British Journal of General Practice and is free to read online.#

The UK media’s coverage of the study was generally accurate. However, when reporting the risks of particular symptoms, the media reports did not make clear that these figures applied only to people aged over 60. So, the use of a photograph of a young woman with a sore throat by the Mail Online is arguably inappropriate and may cause unnecessary alarm.

What kind of research was this?

This was a case control study. Case control studies are used to investigate risk factors associated with a rare outcome, such as laryngeal cancer. In this case, researchers wanted to see what symptoms people reported to GPs in the year before being diagnosed with laryngeal cancer, and whether these reports were more common in people with cancer than without.

What did the research involve?

Researchers used anonymised patient information from the UK’s Clinical Practice Research Datalink network of more than 600 general practices. They found all cases of people 40 or over, diagnosed with laryngeal cancer between 2000 and 2009, who had a record of a consultation with a GP in the year before their diagnosis. They then matched them with up to 5 patients from the same practice, of the same age and sex.

The researchers conducted a literature search and looked on patient forums to find any symptoms that had previously been linked to laryngeal cancer. They focused on 10 commonly reported symptoms, then looked for reports of these symptoms in the records of the people in the study, to see how often they’d been reported to GPs by people with or without laryngeal cancer.

The researchers used the data to calculate the positive predictive value of symptoms alone or in combination. Positive predictive value tells you what percentage of people with that symptom have the disease in question. Importantly, the calculation was done for people aged over 60, because there were few people with laryngeal cancer in younger age groups.

What were the basic results?

The study confirmed that hoarseness is the single symptom most closely linked with laryngeal cancer. 52% of people diagnosed with laryngeal cancer had reported hoarseness in the year before diagnosis, compared to 0.25% of people without cancer.

The researchers calculated that 2.7% of people over 60 reporting hoarseness would have laryngeal cancer. No other symptom was as strongly linked to cancer on its own. However, other combinations of symptoms did raise the risk. For people over 60 with hoarseness, the likelihood of cancer rose further if they also had insomnia (5.2% of people with both symptoms having cancer), persistent shortness of breath (7.9% of people), mouth symptoms (4.1%), blood tests that showed inflammation (15%), earache (6.3%), difficulty swallowing (3.5%), or persistent sore throat (12%).

For people over 60 without hoarseness, 3% or more of people with the following combination of symptoms were found to have laryngeal cancer:

persistent sore throat with: shortness of breath (4.1%), blood tests showing inflammation (3%), persistent chest infection (3%), earache (3%), difficulty swallowing (4.1%)

sore throat with: shortness of breath (5.2%), earache (6.3%) or difficulty swallowing (6.9%)

difficulty swallowing with earache (3%)

How did the researchers interpret the results?

The researchers said: “These results provide new evidence that GPs should consider relevant when ascertaining whether to refer a patient for suspected laryngeal cancer.”

They point out that chances of laryngeal cancer “rose considerably” when hoarseness thought to be down to an infection persisted, and say GPs should “encourage re-attendance should the hoarseness persist”.

Conclusion

This study provides useful information for GPs about which symptoms, together or in isolation, might warrant a referral for investigation for possible laryngeal cancer.

The study has some limitations. The researchers relied on the GPs to record symptoms accurately and consistently, and say they may have missed some symptoms recorded in free text boxes rather than coded separately. People diagnosed with laryngeal cancer saw GPs more often, so had more chance to report symptoms. That means some people without cancer may have had symptoms such as sore throat, but did not report them. This could slightly overestimate the risk attached to symptoms.

The research provides new evidence to help GPs weigh up which patients may need referral for investigation, and which should be followed up to ensure their symptoms resolve. Even then, the study authors make the point that selecting the right patients for investigation of possible cancer “is not simply a matter of totting up symptoms and PPVs (positive predictive values)”. They say GPs’ clinical experience is also important for making these decisions.

However, there’s no need to panic if you get a sore throat. The vast majority of sore throats are caused by colds or infections. They pass quickly and often need no treatment. Sore throats, ear aches and other symptoms of infection are particularly common in children and young people. Even among older adults, the proportion of people with a sore throat or other symptoms who will be found to have laryngeal cancer is still very low.

However, people should get persistent symptoms – alone or in combination – checked out, especially if they last longer than you’d expect from a cold or chest infection.

Why haven’t we found a cure for cancer yet?

Cancer is more difficult to cure than you might think. It is a series of related diseases, not just one disease, complicating things greatly.

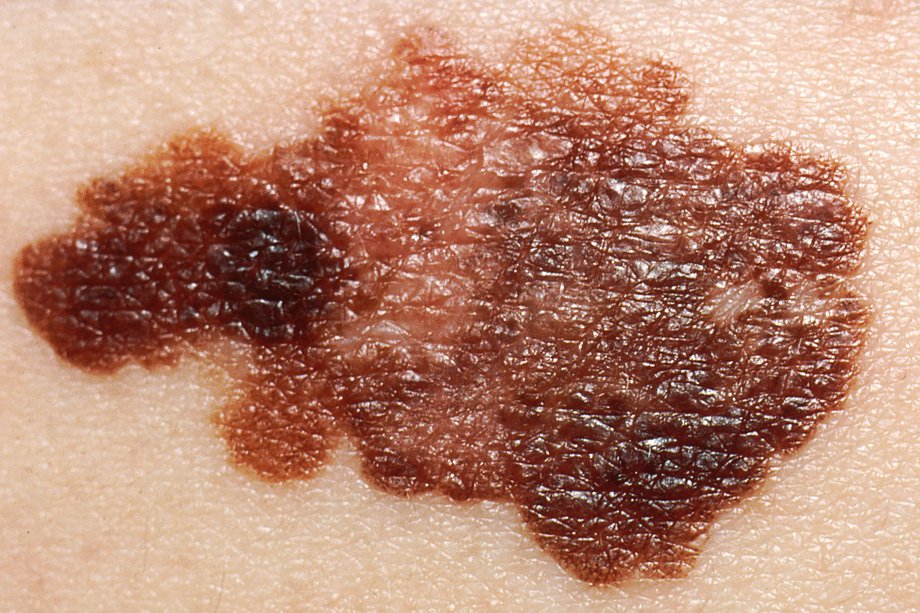

What are the signs and symptoms of melanoma?

The first sign of a melanoma is often a new mole or a change in the appearance of an existing mole.

Normal moles are generally round or oval, with a smooth edge, and usually no bigger than 6mm (1/4 inch) in diameter.

But size isn’t a sure sign of melanoma. A healthy mole can be larger than 6mm in diameter, and a cancerous mole can be smaller than this.

See your GP as soon as possible if you notice changes in a mole, freckle or patch of skin, particularly if the changes happen over a few weeks or months.

Signs to look out for include a mole that’s:

getting bigger

changing shape

changing colour

bleeding or becoming crusty

itchy or sore

The ABCDE checklist should help you tell the difference between a normal mole and a melanoma:

Asymmetrical – melanomas have 2 very different halves and are an irregular shape

Border – melanomas have a notched or ragged border

Colours – melanomas will be a mix of 2 or more colours

Diameter – most melanomas are larger than 6mm (1/4 inch) in diameter

Enlargement or elevation – a mole that changes size over time is more likely to be a melanoma

Melanomas can appear anywhere on your body, but they most commonly appear on the back in men and on the legs in women.

They can also develop underneath a nail, on the sole of the foot, in the mouth or in the genital areas, but these types of melanoma are rare.

Melanoma of the eye

In rare cases, melanoma can develop in the eye. It develops from pigment-producing cells called melanocytes.

Eye melanoma usually affects the eyeball. The most common type is uveal or choroidal melanoma, which occurs at the back of the eye.

Very rarely, it can occur on the thin layer of tissue that covers the front of the eye (the conjunctiva) or in the coloured part of the eye (the iris).

Noticing a dark spot or changes in vision can be signs of eye melanoma, although it’s more likely to be diagnosed during a routine eye examination.

Read more about melanoma of the eye.

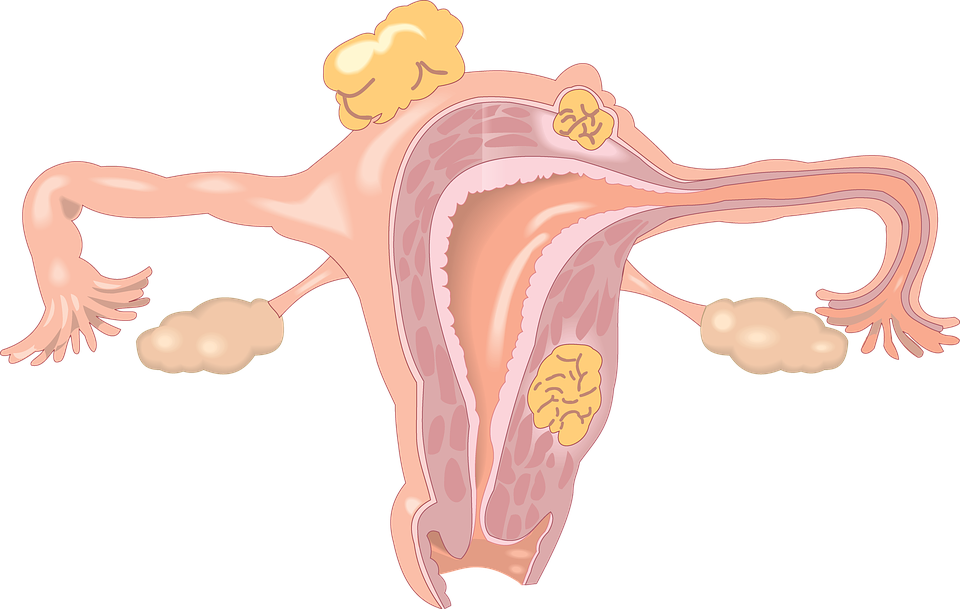

Womb cancer – What are the early signs and symptoms of womb cancer?

The most common symptom of womb cancer is abnormal bleeding from the vagina, although most people with abnormal bleeding don’t have cancer.

Bleeding may start as light bleeding accompanied by a watery discharge, which may get heavier over time. Most women diagnosed with womb cancer have been through the menopause, so any vaginal bleeding will be unusual.

In women who haven’t been through the menopause, unusual vaginal bleeding may consist of:

periods that are heavier than usual

vaginal bleeding in between normal periods

Less common symptoms include pain in the lower abdomen (tummy) and pain during sex.

If womb cancer reaches a more advanced stage, it may cause additional symptoms. These include:

pain in the back, legs, or pelvis

loss of appetite

tiredness

nausea

When to seek medical advice

If you have postmenopausal vaginal bleeding, or notice a change in the normal pattern of your period, visit your GP.

Only 1 in 10 cases of unusual vaginal bleeding after the menopause are caused by womb cancer, so it’s unlikely your symptoms will be caused by this condition.

However, if you have unusual vaginal bleeding, it’s important to get the cause of your symptoms investigated. The bleeding may be the result of a number of other potentially serious health conditions, such as:

endometriosis – where tissue that behaves like the lining of the womb is found on the outside of the womb

fibroids – non-cancerous growths that can develop inside the uterus

polyps in the womb lining

Other types of gynaecological cancer can also cause unusual vaginal bleeding, particularly cervical cancer.