Noonan syndrome can affect a person in many different ways. Not everyone with the disorder will share the same characteristics.

The three most common characteristics of Noonan syndrome are:

unusual facial features

short stature (restricted growth)

heart defects present at birth (congenital heart disease)

These are discussed in more detail below.

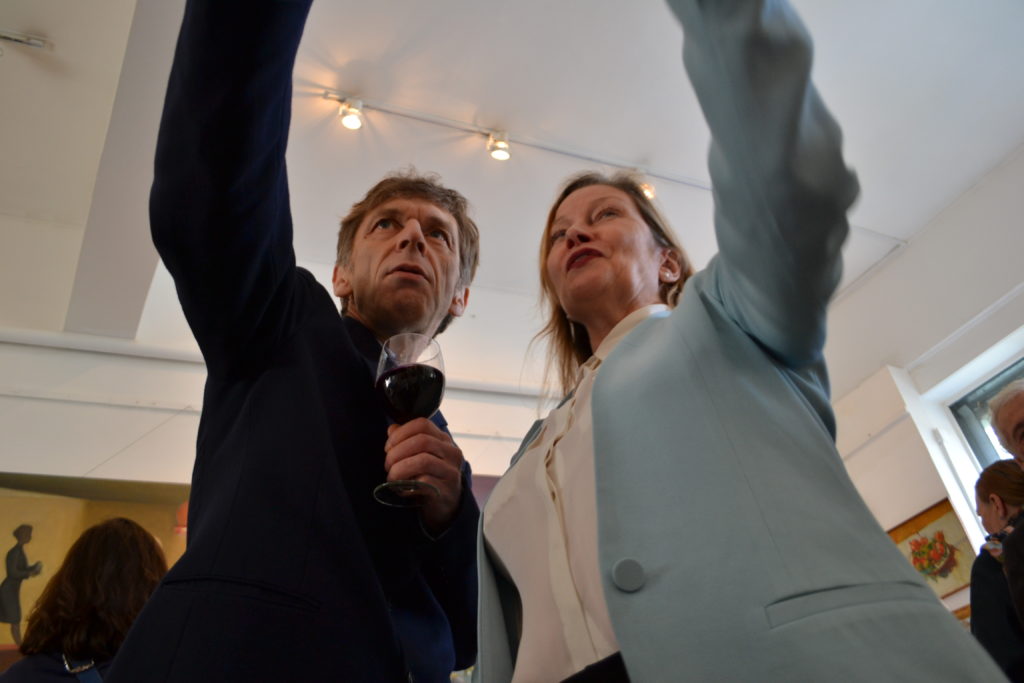

Unusual features

People with Noonan syndrome may have a characteristic facial appearance, although this isn’t always the case.

The following features may become apparent soon after birth:

a broad forehead

drooping eyelids (ptosis)

a wider-than-usual distance between the eyes

a short, broad nose

low-set ears that are rotated towards the back of the head

a small jaw

a short neck with excess skin folds

a lower-than-usual hairline at the back of the head and neck

Children with Noonan syndrome also have abnormalities that affect the bones of the chest. For example, their chest may stick out or sink in, or they may have an usually wide chest with a large distance between the nipples.

These features may be more obvious in early childhood, but tend to become much less noticeable in adulthood.

Short stature

Children with Noonan syndrome are usually a normal length at birth. However, at around two years old you may notice that they don’t grow as quickly as other children of the same age.

Puberty (when a child begins to mature sexually and physically) typically occurs a few years later than normal and the expected growth spurt that normally happens during puberty is either reduced or doesn’t happen at all.

Medication known as human growth hormone can sometimes help children reach a more normal height. Left untreated, the average adult height for men with Noonan syndrome is 162.5cm (5ft 3in) and for women is 153cm (5ft).

Heart defects

Most children with Noonan syndrome will have some form of congenital heart disease. This is usually one of the following:

pulmonary stenosis – where the pulmonary valve (the valve that helps control the flow of blood from the heart to the lungs) is unusually narrow, which means the heart has to work much harder to pump blood into the lungs

hypertrophic cardiomyopathy – where the muscles of the heart are much larger than they should be, which can place a strain on the heart

septal defects – a hole between two of the chambers of the heart (a “hole in the heart”), which can cause the heart to enlarge and/or lead to high pressure in the lungs

Read more about the different types of congenital heart disease.

Other characteristics

Other less common characteristics of Noonan syndrome can include:

learning disability – children with Noonan syndrome tend to have a slightly lower-than-average IQ and a small number have learning disabilities, though these are often mild

feeding problems – babies with Noonan syndrome may have problems sucking and chewing, and may vomit soon after eating

behavioural problems – some children with Noonan syndrome may be fussy eaters, behave immaturely compared to children of a similar age, have problems with attention and have difficulty recognising or describing their or other people’s emotions

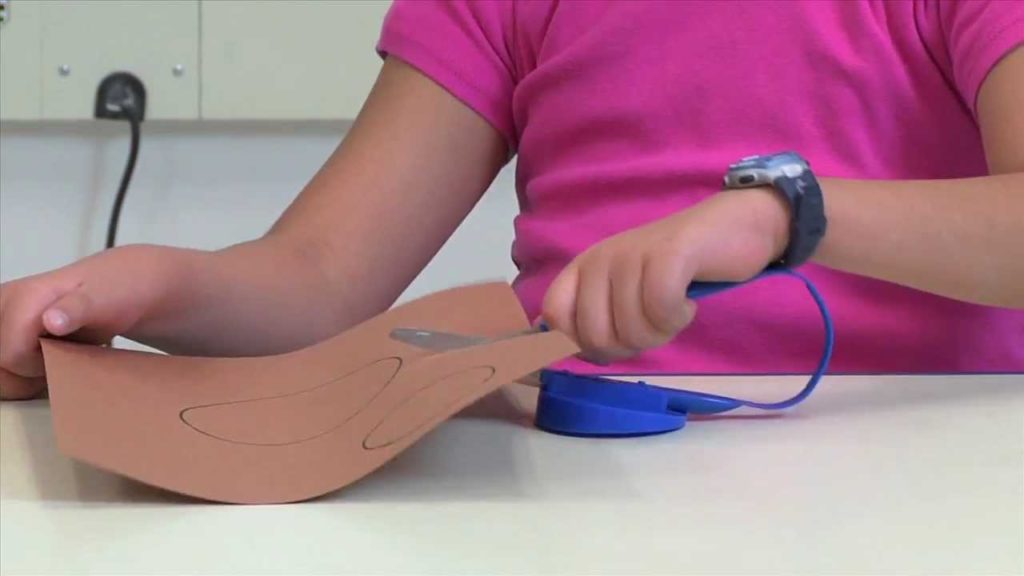

increased bruising or bleeding – sometimes the blood doesn’t clot properly, which can make children with Noonan syndrome more vulnerable to bruising and heavy bleeding from cuts or medical procedures

eye conditions – including a squint (where the eyes point in different directions), a lazy eye (where one eye is less able to focus) and/or astigmatism (slightly blurred vision caused by the front of the eye being an irregular shape)

hypotonia – decreased muscle tone, which can mean it takes your child a bit longer to reach early developmental milestones

undescended testicles – in boys with Noonan syndrome, one or both testicles may fail to drop into the scrotum (sack of skin that holds the testicles)

infertility – especially if undescended testicles aren’t corrected at an early age, there’s a risk of boys with Noonan syndrome having reduced fertility; fertility in girls is usually unaffected

lymphoedema – a build-up of fluid in the lymphatic system (a network of vessels and glands distributed throughout the body)

bone marrow problems – a small number of people can develop an abnormal white blood cell count; this can sometimes get better on its own, but can occasionally turn into leukaemia

A variety of different tumours (cancerous growths) have also been found in people with Noonan syndrome, but it’s often not clear if these are caused by the condition or occur by chance.

Overall, the risk of developing cancer doesn’t appear to be much higher than for people without Noonan syndrome, although there may be a very small increased risk of some rare childhood cancers.