28 Celebrities You Wouldn’t Guess Are Battling Horrific Diseases

A to Z of Medical Conditions

Urticaria- so what are the signs and symptoms of hives?

Urticaria – also known as hives, weals, welts or nettle rash – is a raised, itchy rash that appears on the skin. It may appear on one part of the body or be spread across large areas.

The rash is usually very itchy and ranges in size from a few millimetres to the size of a hand.

Although the affected area may change in appearance within 24 hours, the rash usually settles within a few days.

Doctors may refer to urticaria as either:

acute urticaria – if the rash clears completely within six weeks

chronic urticaria – in rarer cases, where the rash persists or comes and goes for more than six weeks, often over many years

A much rarer type of urticaria, known as urticaria vasculitis, can cause blood vessels inside the skin to become inflamed. In these cases, the weals last longer than 24 hours, are more painful, and can leave a bruise.

When to seek medical advice

Visit your GP if your symptoms don’t go away within 48 hours.

You should also contact your GP if your symptoms are:

severe

causing distress

disrupting daily activities

occurring alongside other symptoms

Who’s affected by urticaria?

Acute urticaria (also known as short-term urticaria) is a common condition, estimated to affect around one in five people at some point in their lives.

Children are often affected by the condition, as well as women aged 30 to 60, and people with a history of allergies.

Chronic urticaria (also known as long-term urticaria) is much less common, affecting up to five in every 1,000 people in England.

What causes urticaria?

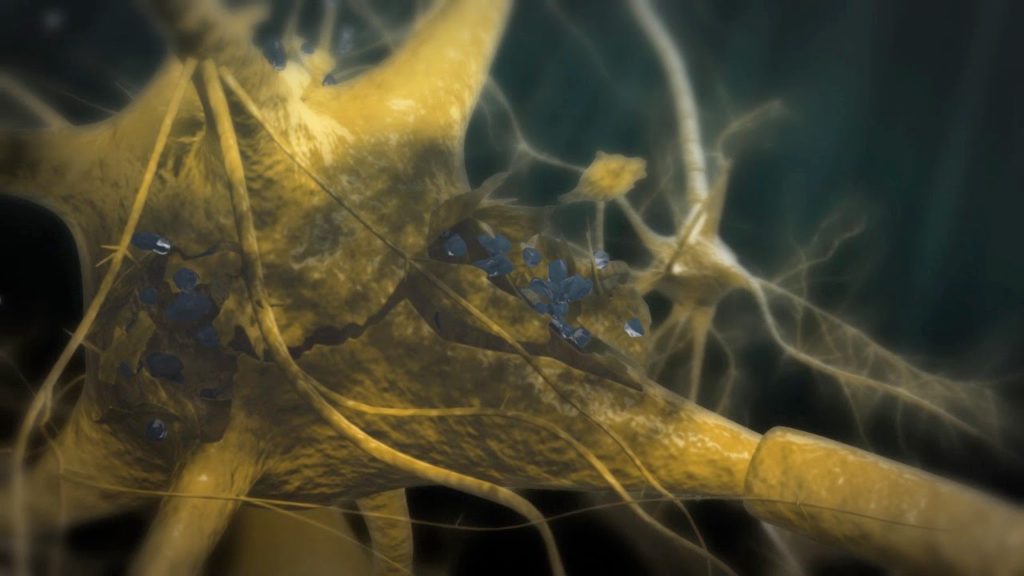

Urticaria occurs when a trigger causes high levels of histamine and other chemical messengers to be released in the skin.

These substances cause the blood vessels in the affected area of skin to open up (often resulting in redness or pinkness) and become leaky. This extra fluid in the tissues causes swelling and itchiness.

Histamine is released for many reasons, including:

an allergic reaction – such as a food allergy or a reaction to an insect bite or sting

cold or heat exposure

infection – such as a cold

certain medications – such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or antibiotics

However, in many cases of urticaria, no obvious cause can be found.

Some cases of long-term urticaria may be caused by the immune system mistakenly attacking healthy tissue. However, this is difficult to diagnose and the treatment options are the same.

Certain triggers may also make the symptoms worse. These include:

drinking alcohol or caffeine

emotional stress

warm temperature

Read more about the causes of urticaria.

Diagnosing urticaria

Your GP will usually be able to diagnose urticaria by examining the rash. They may also ask you questions to find out what triggered your symptoms.

If your GP thinks that it’s caused by an allergic reaction, you may be referred to an allergy clinic for an allergy test. However, if you’ve had urticaria most days for more than six weeks, it’s unlikely to be the result of an allergy.

You may also be referred for a number of tests, including a full blood count (FBC), to find out whether there’s an underlying cause of your symptoms.

Read more about diagnosing urticaria.

Treating urticaria

In many cases, treatment isn’t needed for urticaria, because the rash often gets better within a few days.

If the itchiness is causing you discomfort, antihistamines can help. Antihistamines are available over the counter at pharmacies – speak to your pharmacist for advice.

A short course of steroid tablets (oral corticosteroids) may occasionally be needed for more severe cases of urticaria.

If you have persistent urticaria, you may be referred to a skin specialist (dermatologist). Treatment usually involves medication to relieve the symptoms, while identifying and avoiding potential triggers.

Read about treating urticaria.

Complications of urticaria

Around a quarter of people with acute urticaria and half of people with chronic urticaria also develop angioedema, which is a deeper swelling of tissues.

Chronic urticaria can also be upsetting and negatively impact a person’s mood and quality of life.

Angioedema

Angioedema is swelling in the deeper layers of a person’s skin. It’s often severe and is caused by a build-up of fluid. The symptoms of angioedema can affect any part of the body, but usually affect the:

eyes

lips

genitals

hands

feet

Medication such as antihistamines and short courses of oral corticosteroids (tablets) can be used to relieve the swelling.

Read more about treating angioedema.

Emotional impact

Living with any long-term condition can be difficult. Chronic urticaria can have a considerable negative impact on a person’s mood and quality of life. Living with itchy skin can be particularly upsetting.

One study found that chronic urticaria can have the same negative impact as heart disease. It also found that one in seven people with chronic urticaria had some sort of psychological or emotional problem, such as:

See your GP if your urticaria is getting you down. Effective treatments are available to improve your symptoms.

Talking to friends and family can also improve feelings of isolation and help you cope better with your condition.

Read about how talking to others can help.

Hypoglycaemia – what are the signs and symptoms of Hypoglycaemia?

Introduction

Hypoglycaemia, or a “hypo”, is an abnormally low level of glucose in your blood (less than four millimoles per litre).

When your glucose (sugar) level is too low, your body doesn’t have enough energy to carry out its activities.

Hypoglycaemia is most commonly associated with diabetes, and mainly occurs if someone with diabetes takes too much insulin, misses a meal or exercises too hard.

In rare cases, it’s possible for a person who doesn’t have diabetes to experience hypoglycaemia. It can be triggered by malnutrition, binge drinking or certain conditions, such as Addison’s disease.

Read more about the causes of hypoglycaemia.

Symptoms of hypoglycaemia

Most people will have some warning that their blood glucose levels are too low, which gives them time to correct them. Symptoms usually occur when blood sugar levels fall below four millimoles (mmol) per litre.

Typical early warning signs are feeling hungry, trembling or shakiness, and sweating. In more severe cases, you may also feel confused and have difficulty concentrating. In very severe cases, a person experiencing hypoglycaemia can lose consciousness.

It’s also possible for hypoglycaemia to occur during sleep, which can cause excess sweating, disturbed sleep, and feeling tired and confused upon waking.

Read more about the symptoms of hypoglycaemia.

Correcting hypoglycaemia

The immediate treatment for hypoglycaemia is to have some food or drink that contains sugar, such as dextrose tablets or fruit juice, to correct your blood glucose levels.

After having something sugary, you may need to have a longer-acting “starchy” carbohydrate food, such as a sandwich or a few biscuits.

If hypoglycaemia causes a loss of consciousness, an injection of the hormone glucagon can be given to raise blood glucose levels and restore consciousness. This is only if an injection is available and the person giving the injection knows how to use it.

You should request an ambulance if:

a glucagon injection kit isn’t available

there’s nobody trained to give the injection

the injection is ineffective after 10 minutes

Never try to put food or drink into the mouth of someone who’s drowsy or unconscious as they could choke. This includes some of the high-sugar preparations specifically designed for smearing inside the cheek.

Read more about treating hypoglycaemia.

Preventing hypoglycaemia

If you have diabetes that requires treatment with insulin, the safest way to avoid hypoglycaemia is to regularly check your blood sugar and learn to recognise the early symptoms.

Missing meals or snacks or eating less carbohydrate than planned can increase your risk of hypoglycaemia. You should be careful when drinking alcohol as it can also cause hypoglycaemia, sometimes many hours after drinking.

Exercise or activity is another potential cause, and you should have a plan for dealing with this, such as eating carbohydrate before, during or after exercise, or adjusting your insulin dose.

You should also make sure you regularly change where you inject insulin as the amount of insulin your body absorbs can differ depending on where it’s injected.

Always carry rapid-acting carbohydrate with you, such as glucose tablets, a carton of fruit juice (one that contains sugar), or some sweets in case you feel symptoms coming on or your blood glucose level is low.

Make sure your friends and family know about your diabetes and the risk of hypoglycaemia. It may also help to carry some form of identification that lets people know about your condition in an emergency.

When hypoglycaemia occurs as the result of an underlying condition other than diabetes, the condition will need to be treated to prevent a further hypo.

Read more about preventing hypoglycaemia.

Heat exhaustion and heatstroke – signs, symptoms and treatments -important this time of year

Heat exhaustion and heatstroke are two potentially serious conditions that can occur if you get too hot.

They usually happen during a heatwave or in a hot climate, but can also occur when you’re doing very strenuous physical exercise.

Heat exhaustion is where you become very hot and start to lose water or salt from your body, which leads to the symptoms listed below and generally feeling unwell.

Heatstroke is where the body is no longer able to cool itself and a person’s body temperature becomes dangerously high (sunstroke is when this is caused by prolonged exposure to direct sunlight).

Heatstroke is less common, but more serious. It can put a strain on the brain, heart, lungs, liver and kidneys, and can be life-threatening.

If heat exhaustion isn’t spotted and treated early on, there’s a risk it could lead to heatstroke.

Signs and symptoms

Heat exhaustion or heatstroke can develop quickly over a few minutes, or gradually over several hours or days.

Signs of heat exhaustion can include:

tiredness and weakness

feeling faint or dizzy

a headache

muscle cramps

feeling and being sick

heavy sweating

intense thirst

a fast pulse

urinating less often and having much darker urine than usual

If left untreated, more severe symptoms of heatstroke can develop, including confusion, disorientation, seizures (fits) and a loss of consciousness.

What to do

If you notice that someone has signs of heat exhaustion, you should:

get them to lie down in a cool place – such as a room with air conditioning or somewhere in the shade

remove any unnecessary clothing to expose as much of their skin as possible

cool their skin – use whatever you have available, such as a cool, wet sponge or flannel, cold packs around the neck and armpits, or wrap them in a cool, wet sheet

fan their skin while it’s moist – this will help the water to evaporate, which will help their skin cool down

get them to drink fluids – this should ideally be water, fruit juice or a rehydration drink, such as a sports drink

Stay with the person until they’re feeling better. Most people should start to recover within 30 minutes.

If the person is unconscious, you should follow the steps above and place the person in the recovery position until help arrives (see below). If they have a seizure, move nearby objects out of the way to prevent injury.

When to get medical help

Severe heat exhaustion or heatstroke requires hospital treatment.

You should call an ambulance if:

the person doesn’t respond to the above treatment within 30 minutes

the person has severe symptoms, such as a loss of consciousness, confusion or seizures

Continue with the treatment outlined above until the ambulance arrives.

If the person is feeling better after using the above measures, but you have any concerns about them, contact your GP or NHS 111 for advice.

Who’s most at risk?

Anyone can develop heat exhaustion or heatstroke during a heatwave or while doing heavy exercise in hot weather. However, some people are at a higher risk.

These include:

elderly people

babies and young children

people with a long-term health condition, such as diabetes or a heart or lung condition

people who are already ill and dehydrated (for example, from gastroenteritis)

people doing strenuous exercise for long periods, such as military soldiers, athletes, hikers and manual workers

You’re more likely to experience problems if you’re dehydrated, there’s little breeze or ventilation, or you’re wearing tight, restrictive clothing.

Certain medications can also increase your risk of developing heat exhaustion or heatstroke, including diuretics, antihistamines, beta-blockers, antipsychotics and recreational drugs, such as amphetamines and ecstasy.

How to prevent heat exhaustion and heatstroke

Heat exhaustion and heatstroke can often be prevented by taking sensible precautions when it’s very hot.

During the summer, check for heatwave warnings, so you’re aware when there’s a potential danger. The government uses a system called Heat-Health Watch to warn people about the chances of a heatwave. This is a system of four different warning levels based on the expected temperature.

Public Health England (PHE) has also published a Heatwave plan for England (PDF, 1.19Mb), which suggests following the advice below during a heatwave to help prevent heat-related illnesses.

Stay out of the heat

Keep out of the sun between 11am and 3pm.

If you have to go out in the heat, walk in the shade, apply sunscreen and wear a hat and light scarf.

Avoid extreme physical exertion.

Wear light, loose-fitting cotton clothes.

If you’re travelling to a hot country, be particularly careful for at least the first few days, until you get used to the temperature.

Cool yourself down

Have plenty of cold drinks, and avoid excess alcohol, caffeine and hot drinks.

Eat cold foods, particularly salads and fruit with a high water content.

Take a cool shower or bath.

Sprinkle water over your skin or clothing, or keep a damp cloth on the back of your neck.

If you’re not urinating frequently or your urine is dark, it’s a sign that you’re becoming dehydrated and need to drink more.

Keep your environment cool

Keep windows and curtains that are exposed to the sun closed during the day, but open windows at night when the temperature has dropped.

If possible, move into a cooler room, especially for sleeping.

Electric fans may provide some relief.

Turn off non-essential lights and electrical equipment, as they generate heat.

Keep indoor plants and bowls of water in the house, as these can cool the air.

In the longer term, it can help to have your loft and cavity walls insulated, as this will keep the heat in when it’s cold and keep it out when it’s hot. Using light-coloured, reflective external paint on your house may also be useful.

Look out for others

Keep an eye on isolated, elderly, ill or very young people and make sure they are able to keep cool.

Ensure that babies, children or elderly people are not left alone in stationary cars.

Check on elderly or sick neighbours, family or friends every day during a heatwave.

Be alert and call a doctor or social services if someone is unwell or further help is needed.

Read about how to prepare for a heatwave.

Paraesthesia – what are the signs and symptoms of Paraesthesia?

Pins and needles (paraesthesia) is a pricking, burning, tingling or numbing sensation that’s usually felt in the arms, legs, hands or feet.

It doesn’t usually cause any pain, but it can cause numbness or itching.

Pins and needles is usually temporary, but can sometimes be long-lasting (chronic).

Temporary pins and needles

Most people have temporary pins and needles from time to time.

It happens when pressure is applied to a part of the body, which cuts off the blood supply to the nerves in that area. This prevents the nerves from sending important signals to the brain.

Putting weight on a body part (for example, by kneeling) or wearing tight shoes or socks can potentially cause pins and needles.

Temporary pins and needles can be eased by simply taking the pressure off the affected area. This allows your blood supply to return, relieving the numbness or tingling sensation.

Other common reasons for temporary pins and needles include:

a condition known as Raynaud’s disease – which affects the blood supply to certain areas of the body, such as the fingers and toes, and is usually triggered by cold temperatures or sometimes anxiety or stress

hyperventilating (breathing too quickly)

Long-lasting pins and needles

Sometimes, pins and needles can occur over a long period of time. It can be a sign of a wide range of health conditions, including:

diabetes – a condition in which there is too much glucose in the blood.

a compressed ulnar nerve – the ulnar nerve starts in your neck and runs down the inside of your upper arm to your elbow, then down to the little finger side of your hand; it can be compressed at any point, but the elbow is most commonly affected

carpal tunnel syndrome – pain, numbness and a burning or tingling sensation in the hand caused by a build-up of pressure in the small tunnel that runs from the wrist to the lower palm (the carpal tunnel)

sciatica – pain caused by irritation or compression of the sciatic nerve, which runs from the back of your pelvis, through your buttocks and down both legs to your feet

Persistent pins and needles can also occur after an injury, or be caused by certain treatments, such as chemotherapy.

When to see your GP

Most cases of pins and needles are temporary and the sensation disappears after the pressure is taken off the affected area.

See your GP if you constantly have pins and needles or if it keeps coming back. It may be a sign of a more serious underlying health condition.

Treatment for chronic pins and needles depends on the cause. For example, if it’s caused by diabetes, treatment will focus on controlling your blood glucose levels.

Other causes

Long-lasting pins and needles may also be caused by:

a condition that damages the nervous system – such as a stroke, multiple sclerosis or in extremely rare cases, a brain tumour

exposure to toxic substances – such as lead or radiation

certain types of medication – such as HIV medication, medication to prevent seizures (anticonvulsants), or some antibiotics

malnutrition – where the body lacks important nutrients because of a poor diet

nerve damage caused by infection, injury or overuse – for example, a condition known as hand-arm vibration syndrome may be the result of regularly using vibrating tools

cervical spondylosis – the bones and tissues of the spine can wear down over time, leading to trapped nerves and occasionally pins and needles