Kawasaki disease is a rare condition that mainly affects children under the age of five. It’s also known as mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome.

The characteristic symptoms are a high temperature that lasts for more than five days, with:

a rash

swollen glands in the neck

dry, cracked lips

red fingers or toes

red eyes

After a few weeks the symptoms become less severe, but may last longer. At this stage, the affected child may have peeling skin on their fingers and toes.

The symptoms of Kawasaki disease usually develop in three phases over a six-week period.

The three phases are described below.

Phase 1: acute (weeks 1-2)

Your child’s symptoms will appear suddenly and may be severe.

High temperature

The first and most common symptom of Kawasaki disease is usually a high temperature (fever) of 38C (100.4F) or above.

The fever can come on quickly and doesn’t respond to antibiotics or medicines typically used to reduce a fever, such as ibuprofen or paracetamol. If your child has a fever, they may be very irritable.

Your child’s fever will usually last for at least five days. However, it can last for around 11 days without the proper treatment. In some rare cases, the fever can last for as long as three to four weeks.

The fever may come and go, and your child’s body temperature could possibly reach a high of 40C (104F).

Rash

Your child may have a blotchy, red rash on their skin. It usually starts in the genital area before spreading to the torso, arms, legs and face.

The spots are usually red and raised, but there will not be any blistering.

Read more about skin rashes in children.

Hands and feet

The skin on your child’s fingers or toes may become red or hard, and their hands and feet may swell up.

Your child may feel their hands and feet are tender and painful to touch or put weight on, so they may be reluctant to walk or crawl while these symptoms persist.

Conjunctival injection

Conjunctival injection is where the whites of the eyes become red and swollen. Both eyes are usually affected, but the condition isn’t painful.

Unlike conjunctivitis, where the thin layer of cells that cover the white part of the eye (conjunctiva) becomes inflamed, fluid doesn’t leak from the eyes in conjunctival injection.

Lips, mouth, throat and tongue

Your child’s lips may be red, dry or cracked. They may also swell up and peel or bleed.

The inside of your child’s mouth and throat may also be inflamed. Their tongue may be red, swollen and covered in small lumps, also known as “strawberry tongue”.

Swollen lymph glands

If you gently feel your child’s neck, you may be able to feel swollen lumps on one or both sides. The lumps could be swollen lymph glands.

Lymph glands are part of the immune system, the body’s defence against infection. They may swell to over 1.5cm wide, feel firm and be slightly painful.

Phase 2: sub-acute (weeks 2-4)

During the sub-acute phase, your child’s symptoms will become less severe but may last longer. The fever should subside, but your child may still be irritable and in considerable pain.

Symptoms during the second phase of Kawasaki disease may include:

peeling skin on the fingers and toes – also sometimes on the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet

abdominal pain

vomiting

urine that contains pus

feeling drowsy and lacking energy (lethargic)

joint pain and swollen joints

yellowing of the skin and the whites of the eyes (jaundice)

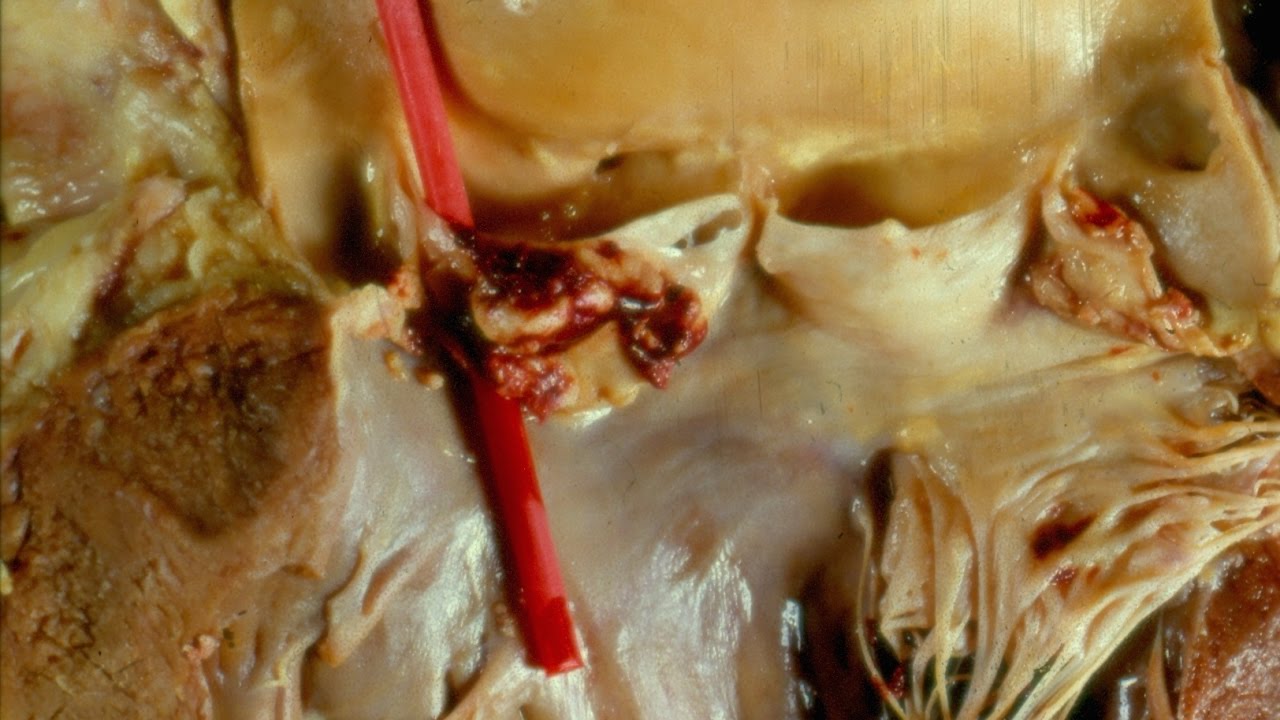

It’s during the second phase of Kawasaki disease that complications are more likely to develop, such as a coronary artery aneurysm, which is a bulge in one of the blood vessels that supply blood to the heart.

Read more about the complications of Kawasaki disease.

Phase 3: convalescent (weeks 4-6)

Your child will begin to recover during the third phase of Kawasaki disease, which is known as the convalescent phase.

Your child’s symptoms should begin to improve and all signs of the illness should eventually disappear. However, your child may still have a lack of energy and become easily tired during this time.

Occasionally, complications can develop during the third phase of Kawasaki disease, but they’re more likely to develop before this stage.