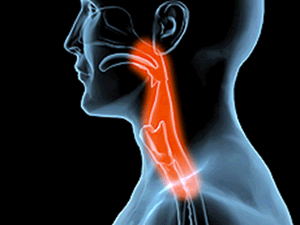

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) (also known as acid reflux) is a common condition where acid from the stomach leaks out of the stomach and up into the oesophagus (gullet).

he oesophagus is a long tube of muscle that runs from the mouth to the stomach.

Common symptoms of GORD include:

- heartburn – burning chest pain or discomfort that occurs after eating

- acid reflux – you may have an unpleasant taste in the mouth, caused by stomach acid coming back up into your mouth

- pain when swallowing (odynophagia)

- difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

GORD occurs only occasionally for some people, but if the symptoms persist it’s usually regarded as a condition that needs treatment.

Read more about the symptoms of GORD.

What causes GORD?

It’s thought that GORD is caused by a combination of factors, but the most common is the failure of the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) – a ring of muscle towards the bottom of the oesophagus.

This acts like a valve, opening to let food fall into the stomach, then closing to prevent acid leaking out of the stomach.

In GORD, this sphincter doesn’t close properly, allowing acid to leak up out of the stomach.

Known risk factors for GORD include:

- being overweight or obese

- being pregnant

- eating a high-fat diet

Read more about the causes of GORD.

Diagnosing GORD

Your GP should be able to diagnose and treat GORD by asking you about your symptoms.

Further testing is usually only required if you have pain or difficulty swallowing, or if your symptoms don’t improve despite taking medication.

Testing usually involves using an instrument called an endoscope, which is a long, thin, flexible tube with a light and camera at one end. It will be gently lowered down your throat so that any acid damage to the oesophagus can be seen.

Endoscopy is usually used if the diagnosis of GORD is in doubt, to check for any other possible causes of your symptoms, such as functional dyspepsia (an irritable stomach or gullet) or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Read more about diagnosing GORD.

Treating GORD

A step-by-step approach is usually used for treating GORD. This means that simple treatments, such as changing your diet, will be tried first.

If this proves ineffective in controlling your symptoms, medication – such as antacids, proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) or H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) – may be recommended.

Antacids neutralise the effects of stomach acid, and PPIs and H2RAs reduce the amount of acid that the stomach produces.

Surgery may be required in cases where medication fails to control the symptoms of GORD.

Read more about the treatment of GORD.

Complications

A common complication of GORD is that the stomach acid can irritate and inflame the lining of the oesophagus. This is known as oesophagitis.

In severe cases of oesophagitis, ulcers (open sores) can form, which can cause pain and make swallowing difficult, particularly if the gullet becomes narrowed (stricture).

Cancer of the oesophagus, known as oesophageal cancer, is a rarer and more serious complication of GORD.

Read more about the complications of GORD.

Outlook

Most people initially respond well to treatment with medication, but symptoms can often return quite quickly (within days or weeks).

People with recurring GORD may need to take medication on a long-term basis.