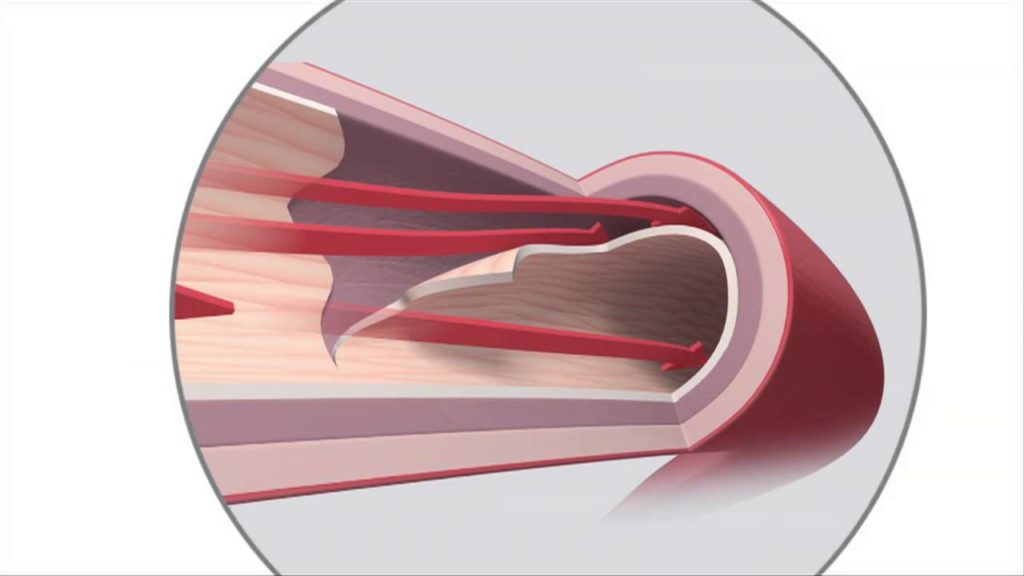

Atherosclerosis is a potentially serious condition where arteries become clogged with fatty substances called plaques, or atheroma.

These plaques cause the arteries to harden and narrow, restricting the blood flow and oxygen supply to vital organs, and increasing the risk of blood clots that could potentially block the flow of blood to the heart or brain.

Atherosclerosis doesn’t tend to have any symptoms at first, and many people may be unaware they have it, but it can eventually cause life-threatening problems such as heart attacks and strokes if it gets worse.

However, the condition is largely preventable with a healthy lifestyle, and treatment can help reduce the risk of serious problems occurring.

Health risks of atherosclerosis

If left to get worse, atherosclerosis can potentially lead to a number of serious conditions known as cardiovascular disease (CVD). There won’t usually be any symptoms until CVD develops.

Types of CVD include:

coronary heart disease – the main arteries that supply your heart (the coronary arteries) become clogged with plaques

angina – short periods of tight, dull or heavy chest pain caused by coronary heart disease, which may precede a heart attack

heart attacks – where the blood supply to your heart is blocked, causing sudden crushing or indigestion-like chest pain that can radiate to nearby areas, as well as shortness of breath and dizziness

strokes – where the blood supply to your brain is interrupted, causing the face to droop to one side, weakness on one side of the body, and slurred speech

transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs) – where there are temporary symptoms of a stroke

peripheral arterial disease – where the blood supply to your legs is blocked, causing leg pain when walking

Click on the links above for more information about these conditions, including what the main symptoms and risks are.

Who’s at risk of atherosclerosis?

Exactly why and how arteries become clogged is unclear.

It can happen to anyone, although the following things can increase your risk:

increasing age

an unhealthy, high-fat diet

lack of exercise

being overweight or obese

regularly drinking excessive amounts of alcohol

other conditions, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol and diabetes

a family history of atherosclerosis and CVD

being of south Asian, African or African-Caribbean descent

You can’t do anything about some of these factors, but by tackling things such as an unhealthy diet and a lack of exercise, you can help reduce your risk of atherosclerosis and CVD.

Read more about the risk factors for CVD.

Testing for atherosclerosis

Speak to your GP if you’re worried you may be at a high risk of atherosclerosis.

If you’re between the ages of 40 and 74, you should have an NHS Health Check every five years, which will include tests to find out if you’re at risk of atherosclerosis and CVD.

Your GP or practice nurse can work out your level of risk by taking into account factors such as:

your age, gender and ethnic group

your weight and height

if you smoke or have previously smoked

if you have a family history of CVD

your blood pressure and cholesterol levels

if you have certain long-term conditions

Depending on your result, you may be advised to make lifestyle changes, consider taking medication, or have further tests to check for atherosclerosis and CVD.

Reduce your risk of atherosclerosis

Making healthy lifestyle changes can reduce your risk of developing atherosclerosis and may help stop it getting worse.

The main ways you can reduce your risk are:

stop smoking – you can call the NHS Smokefree helpline for advice on 0300 123 1044 or ask your GP about stop smoking treatments; read more advice about stopping smoking

have a healthy diet – avoid foods that are high in saturated fats, salt or sugar, and aim to eat five portions of fruit and vegetables a day; read more healthy diet advice

exercise regularly – aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity such as cycling or fast walking every week, and strength exercises on at least two days a week

maintain a healthy weight – aim for a body mass index (BMI) of 18.5 to 24.9; use the BMI calculator to work out your BMI and read advice about losing weight

moderate your alcohol consumption – men and women are advised not to regularly drink more than 14 alcohol units a week; get tips on cutting down on alcohol

Click on the links above for more information. You can also read more specific advice about preventing CVD.

Treatments for atherosclerosis

There aren’t currently any treatments that can reverse atherosclerosis, but the healthy lifestyle changes suggested above may help stop it getting worse.

Sometimes additional treatment to reduce the risk of problems like heart attacks and strokes may also be recommended, such as:

statins for high cholesterol – read more about treating high cholesterol

medicines for high blood pressure – read more about treating high blood pressure

medicines to reduce the risk of blood clots – such as low-dose aspirin or clopidogrel

dietary changes and medication for diabetes – read more about treating type 1 diabetes and treating type 2 diabetes

a procedure to widen or bypass an affected artery – such as a coronary angioplasty, a coronary artery bypass graft, or a carotid endarterectomy

Click on the links above for more information about what these treatments involve.