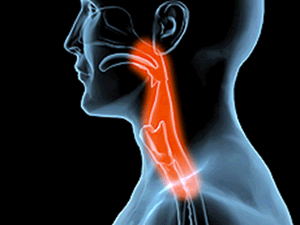

Achalasia is a disorder of the gullet (oesophagus) where it loses the ability to move food along. The valve at the end of the gullet also fails to open and allow food to pass into your stomach.

As a result, food gets stuck in your gullet and is often brought back up.

A ring of muscle called the lower oesophageal (cardiac) sphincter keeps the opening from the gullet to the stomach shut tight to prevent acid reflux (acidic stomach content moving back up into the gullet).

Normally, this muscle relaxes when you swallow to allow the food to pass into your stomach. In achalasia, this muscle does not relax properly and the end of your gullet becomes blocked with food.

Achalasia is an uncommon condition that affects about 6,000 people in Britain. It is sometimes known as cardiospasm.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms of achalasia may start at any time of life and usually come on gradually.

Most people with achalasia have dysphagia, a condition where they find it difficult and sometimes painful to swallow food. This tends to get worse over a couple of years.

It may cause you to bring back up undigested food shortly after meals and some of the vomited food may have been held up in your gullet for some time.

Bringing up undigested food can lead to choking and coughing fits, chest pain and heartburn.

Occasionally, vomit may dribble out of your mouth and stain the pillow during the night. If it trickles down your windpipe, it can cause repeated chest infections and even pneumonia.

You may experience gradual but significant weight loss.

However, in some people achalasia causes no symptoms and is only discovered when a chest X-ray or other investigation is performed for another reason.

What is the cause?

Achalasia is caused by damage to and loss of the nerves in the gullet wall. The reason for this is unknown, although a viral infection earlier in life may be partly responsible.

Achalasia may also be associated with having an autoimmune condition, where the immune system attacks healthy cells, tissue and organs. One recent study found people with achalasia are significantly more likely to have an autoimmune condition such as Sjogren’s syndrome, lupus or uveitis.

Although achalasia can occur at any age, it is more common in middle-aged or older adults.

There is no evidence to suggest that achalasia is an inherited illness. Women with achalasia can have a normal pregnancy and there’s no reason why their children will not develop normally.

How is it diagnosed?

If your GP thinks you have achalasia, you will be referred to hospital to have some diagnostic tests performed.

Barium swallow

A barium swallow involves drinking a white liquid containing the chemical barium, which allows the gullet to be seen and videoed on an X-ray.

In achalasia, the exit at the lower end of your gullet never opens properly, which causes a delay in barium passing into your stomach.

An ordinary chest X-ray may show a wide gullet.

Endoscopy

A flexible instrument called an endoscope is passed down your throat to allow the doctor to look directly at the lining of your gullet and stomach. Trapped food will be visible.

The endoscope can be passed through the tight muscle at the bottom of your gullet and into your stomach to check there is no other disorder of the stomach.

Read more about having an endoscopy.

Manometry

Manometry measures pressure waves in your gullet. A small plastic tube is passed into your gullet through your mouth or nose and the pressure at different points in your gullet is measured.

In achalasia, there are usually weak or absent contractions of the gullet and sustained high pressure in the muscle at the lower end of the gullet. The high pressure means the muscle does not relax in response to swallowing, causing symptoms of achalasia.

How is it treated?

The aim of treatment is to open the lower oesophageal sphincter muscle so food can pass into the stomach easily. The underlying disease cannot be cured but there are various ways to relieve symptoms which can improve swallowing and eating.

Dilatation (stretching the muscle)

A balloon (about 3-4cm in diameter) is used to stretch and disrupt the muscle fibres of the sphincter muscle at the lower end of your gullet.

This usually improves swallowing but may need to be performed several times or repeated after one or more years. Balloon dilatation does carry the risk of oesophageal rupture which may require emergency surgery.

Surgery

Under general anaesthetic the gullet is accessed through the abdomen (tummy) or, rarely, the chest. The muscle fibres of the lower oesophageal sphincter that fail to relax are divided. This usually leads to a permanent improvement in swallowing.

The operation is now performed by keyhole surgery (laparoscopy) and only requires an overnight stay in hospital.

Recovering from treatment

There are a few things you can do after dilatation or surgery to reduce symptoms:

- chew your food well

- take your time eating

- drink plenty of fluids with your meals

- always eat food sitting upright

- use several pillows or raise the head of your bed so that you sleep fairly upright, which prevents stomach acid rising into your gullet through the weakened valve and causing heartburn

If heartburn develops after treatment, consult your GP as medication may be needed to reduce the acid reflux. Sometimes your surgeon may suggest you take this routinely to prevent problems after surgery. Read about treatments for acid reflux.

You should also see your GP if you still have swallowing difficulties or are continuing to lose weight.

It’s normal for chest pain to persist for a while after treatment – drinking cold water often gives relief.

Cancer risk

If the gullet contains a large amount of food that does not pass into the stomach in the normal way, the risk of cancer of the oesophagus (gullet) is slightly increased.

The increased risk is likely to be most significant in long-term untreated achalasia. It’s therefore important to get appropriate treatment for achalasia straight away, even if your symptoms are not bothering you.

According to Cancer Research UK, compared with the general population:

- men with achalasia have an eight to 16 times higher risk of oesophageal cancer

- women with achalasia have a 20 times higher risk of one particular type of oesophageal cancer (adenocarcinoma)

However, cancer of the oesophagus is very uncommon and although your risk is slightly increased, it remains highly unlikely.