Zhen Yan, PhD, an exercise researcher at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, is urging clinical trials of exercise in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia after finding that physical activity has a “profound” protective effect in mouse models of the debilitating genetic disease. Dan Addison | UVA Health

A top exercise researcher at the University of Virginia School of Medicine is urging clinical trials of exercise in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia after finding that physical activity has a “profound” protective effect in mouse models of the debilitating genetic disease.

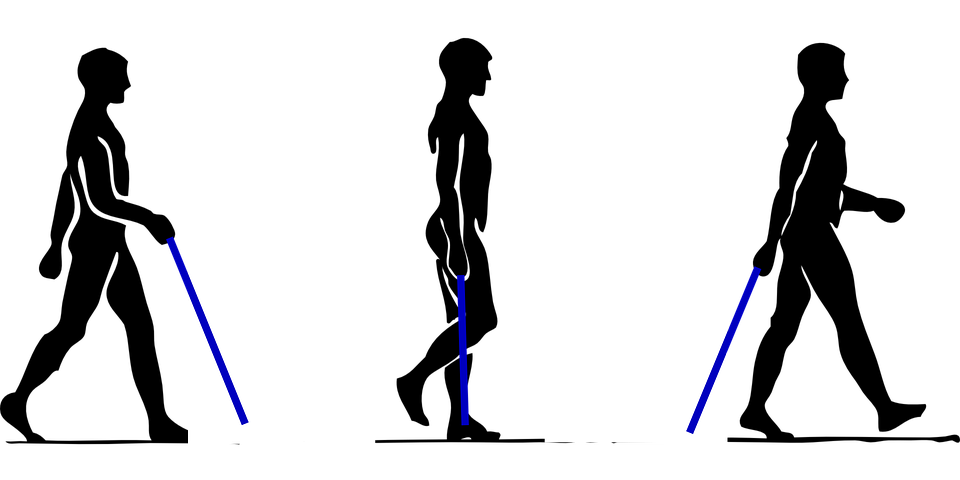

Friedreich’s ataxia typically limits patients’ ability to exercise. But the new findings from UVA’s Zhen Yan, PhD, suggest that well-timed exercise programs early in life may slow the progression of the disease, which robs patients of their ability to walk.

The finding could prove particularly important because genetic testing is currently not mandatory, and there are no effective treatments for the condition.

“When dealing with a genetic disease, we often hope that gene therapy is advanced to a point with great precision and efficiency that we can replace the defect gene in the whole genome and in all the affected cells in the body, but the reality is that we are not there yet,” said Yan, director of the Center for Skeletal Muscle Research at UVA’s Robert M. Berne Cardiovascular Research Center. “This study points to a promising alternative approach of exercise intervention to promote the expression of an iron regulator to bypass the defect gene in maintaining normal mitochondrial function. This could fundamentally change for the good the life of Friedreich’s ataxia patients.”

About Friedreich’s Ataxia

Friedreich’s ataxia affects about 1 in 50,000 people. The disease is caused by a genetic mutation that impairs mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells. Symptoms typically appear between ages 5 and 15, though sometimes later; these symptoms include difficulty moving, poor balance, muscle weakness, type 2 diabetes and heart failure. Patients are often confined to a wheelchair within 10 to 20 years of symptom onset. Some patients with advanced disease become completely incapacitated, and the disease can lead to early death.

In a lab model of the disease, mice lose ability to run, develop blood sugar problems and show signs of moderate heart problems at 6 months of age, But Yan found that mice that started voluntary long-distance running at 2 months completely avoided those problems.

“We conclude that endurance exercise training prevents symptomatic onset of FRDA [Friedreich’s ataxia] in mice associated with improved mitochondrial function and reduced oxidative stress,” the researchers report in a scientific paper on the findings. “These preclinical findings may pave the way for clinical studies of the impact of endurance exercise in FRDA patients.”

The Many Benefits of Exercise

The discovery is the latest in a series from Yan that speaks to the benefits of exercise. He recently made headlines around the world when he determined that exercise may help prevent a potentially deadly complication of COVID-19 known as acute respiratory distress syndrome.

“Unlike drug therapy, increased physical activity has very few side effects. In fact, regular exercise has positive effects to literally all vital organ systems in our body,” he said. “You will benefit from just about any type of exercise as you age, as long as you’re not at risk of injury.”