8 Common early signs of Autism…

8 Common early signs of Autism…

Have you been masking for such a long time that you struggle to unmask? One of the positive effects of masking for autistic people is being socially accepted, but ironically, it also damages our authentic selves.

Long-term autistic masking makes us struggle and be scared to unmask. In this video, we’ll discuss the significant damaging effects of long-term masking and how to help those who heavily mask to slowly rediscover their true selves.

3 Tips to Manage Anxiety

Longer working hours coupled with poor hybrid working posture have led to an explosion in back problems amongst younger working adults

The ‘Covid stone’ – the average weight gain during pandemic has been an issue for many Brits, but hybrid working is now taking a toll on our backs. A new national survey[1] and report commissioned by www.mindyourbackuk.com – backed by Mentholatum[2] — makers of a range of evidence-backed topical muscle and joint products and the brains behind a public health initiative – reveals that 64 per cent of 18–29-year-olds have back problems.

With back pain already costing the UK £10 billion per year and accounting for four in ten sick days,[3] it’s clear we need to take action to stop back issues spiralling out of control.

GP and advisor to www.mindyourbackuk.com, Dr Gill Jenkins, says: “For the six in ten Brits who have been mostly or always working from home during the pandemic and are now hybrid working, almost half don’t have constant access to a table and supportive chair during their working day. And unfortunately, 20 per cent have to work while sitting on a sofa or bed. This plays absolute havoc with posture and spine health”.

The www.mindyourbackuk.com survey also found that some workers working from home or hybrid working have been forced to buy their own specialist chairs (17%) as only 11% received work station equipment from their employers.

While the average working day has increased by 48 minutes worldwide[4], many Brits are doing less exercise to compensate for this. A fifth of those polled admitted to doing no exercise at all in a typical working week and just 7 per cent got up to walk around and stretch every hour – which is recommended for desk work.

The reasons for this include a lack of motivation – cited by 46 per cent – and being pushed for time (37 per cent) or lacking energy (26 per cent) – all very bad news for our backs.

Of the people who had experienced new back pain, more than half (56 per cent) said they have lower back pain compared with 23 per cent who have pain in the neck or shoulder blades. Lower back and neck pain are common complaints when screens are not at eye level, or chairs fail to support the back, allowing desk workers to slump.

Dr Jenkins comments: “Caring for our backs can reduce stress and boost energy so we can live our lives to the full, without pains and aches holding us back. We can’t hurry the lockdown easing but we can do things at home to care for our backs. The Mind Your Back 5 S.T.E.P.S. programme[5] keeps your back mobile, flexible and active, and is easy to incorporate into daily life”.

Mind Your Back 5 S.T.E.P.S. programme

Five simple S.T.E.P.S. for home working back care:

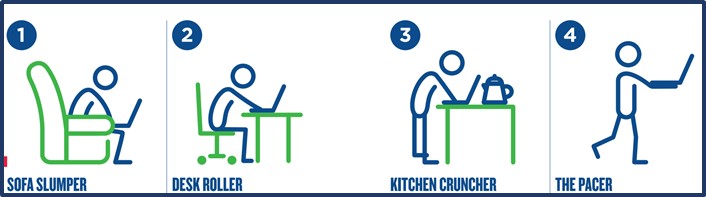

What kind of home worker are you?

#1. Sofa Slumper

You are comfier on the sofa than sat at a table and often find yourself craning over a small screen. Hours can pass as you slide further down the sofa and although you might feel zen, your back is crying out for a posture reset. What’s more, after taking a break to go and eat, you’re back on the sofa to watch TV. Will your spine ever be upright?

Dr Jenkins tip: Place a cushion under your bottom and behind your back to correct your posture.

#2. Desk Roller

You are replicating the office environment: a desk, a chair and you’re (hopefully) sat upright. However, it can be tricky to avoid hunching over a laptop screen unless you’re set up with a big at-eye-level monitor. Tense shoulders and posture that slumps as the day goes on can wreak havoc with your poor back.

Dr Jenkins tip: Make sure your screen is at eye level by placing your laptop on a stack of books.

#3. Kitchen Cruncher

A lack of space means standing at your kitchen worktop squeezed in between the blender and kettle. Naturally, a worktop doesn’t offer the comfiest work stations and your spine soon finds itself curled over a keyboard for hours on end. You might even start placing all your weight on one leg, causing an imbalance in your spine.

Dr Jenkins tip: Ensure that both feet are flat on the floor at any given time and that you focus on standing up straight.

#4. The Pacer

Whether through choice, or lack of space, classic traits of a Pacer involve wandering from room to room, carrying the laptop in one arm and often, a phone in the other. It’s a case of working wherever there’s space, even if it’s crossed legged on the floor which has a tendency to put your back into a slumped position.

Dr Jenkins tip: Walking around is better than sitting but make sure you use a couple of cushions when you sit on the floor and try to keep your screen as close as possible to eye level.

Check out www.mindyourbackuk.com for more tips on caring for your back.

Technicians observe an fMRI brain scan in progress at the Intermountain Neuroimaging Consortium facility on the CU Boulder campus. CREDIT Glenn Asakawa/CU Boulder

Rethinking what causes pain and how great of a threat it is can provide chronic pain patients with lasting relief and alter brain networks associated with pain processing, according to new University of Colorado Boulder-led research.

The study, published Sept. 29 in JAMA Psychiatry, found that two-thirds of chronic back pain patients who underwent a four-week psychological treatment called Pain Reprocessing Therapy (PRT) were pain-free or nearly pain-free post-treatment. And most maintained relief for one year.

The findings provide some of the strongest evidence yet that a psychological treatment can provide potent and durable relief for chronic pain, which afflicts one in five Americans.

“For a long time we have thought that chronic pain is due primarily to problems in the body, and most treatments to date have targeted that,” said lead author Yoni Ashar, who conducted the study while earning his PhD in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at CU Boulder. “This treatment is based on the premise that the brain can generate pain in the absence of injury or after an injury has healed, and that people can unlearn that pain. Our study shows it works.”

Misfiring neural pathways

Approximately 85% of people with chronic back pain have what is known as “primary pain,” meaning tests are unable to identify a clear bodily source, such as tissue damage.

Misfiring neural pathways are at least partially to blame: Different brain regions—including those associated with reward and fear—activate more during episodes of chronic pain than acute pain, studies show. And among chronic pain patients, certain neural networks are sensitized to overreact to even mild stimuli.

If pain is a warning signal that something is wrong with the body, primary chronic pain, Ashar said, is “like a false alarm stuck in the ‘on’ position.”

PRT seeks to turn off the alarm.

“The idea is that by thinking about the pain as safe rather than threatening, patients can alter the brain networks reinforcing the pain, and neutralize it,” said Ashar, now a postdoctoral researcher at Weill Cornell Medicine.

For the randomized controlled trial, Ashar and senior author Tor Wager, now the Diana L. Taylor Distinguished Professor in Neuroscience at Dartmouth College, recruited 151 men and women who had back pain for at least six months at an intensity of at least four on a scale of zero to 10.

Those in the treatment group completed an assessment followed by eight one-hour sessions of PRT, a technique developed by Los Angeles-based pain psychologist Alan Gordon. The goal: To educate the patient about the role of the brain in generating chronic pain; to help them reappraise their pain as they engage in movements they’d been afraid to do; and to help them address emotions that may exacerbate their pain.

Pain is not ‘all in your head’

“This isn’t suggesting that your pain is not real or that it’s ‘all in your head’,” stressed Wager, noting that changes to neural pathways in the brain can linger long after an injury is gone, reinforced by such associations. “What it means is that if the causes are in the brain, the solutions may be there, too.”

Before and after treatment, participants also underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans to measure how their brains reacted to a mild pain stimulus.

After treatment, 66% of patients in the treatment group were pain-free or nearly pain-free compared to 20% of the placebo group and 10% of the no-treatment group.

“The magnitude and durability of pain reductions we saw are very rarely observed in chronic pain treatment trials,” Ashar said, noting that opioids have yielded only moderate and short-term relief in many trials.

And when people in the PRT group were exposed to pain in the scanner post-treatment, brain regions associated with pain processing – including the anterior insula and anterior midcingulate —had quieted significantly.

The authors stress that the treatment is not intended for “secondary pain” – that rooted in acute injury or disease.

The study focused specifically on PRT for chronic back pain, so future, larger studies are needed to determine if it would yeild similar results for other types of chronic pain.

Meanwhile, other similar brain-centered techniques are already ememrging among physical therapists and other clinicians who treat pain.

“This study suggests a fundamentally new way to think about both the causes of chronic back pain for many people and the tools that are available to treat that pain,” said co-author Sona Dimidjian, professor of psychology and neuroscience and director of the Renee Crown Wellness Institute at CU Boulder. “ It provides a potentially powerful option for people who want to live free or nearly free of pain.”